x 19

Questions

An interview for Riluxa

In November 2018, themodernhouse.com cited London-based architect William Smalley as one of, ´The best British architects to follow on Instagram.’ It’s easy to see why. His endlessly photogenic work juxtaposes old and ultramodern in a way that denotes a deep empathy for both, as well as a respect for nature and a lifelong fascination with the limitless potential of the built environment. Nick Mitchell Maiato was delighted to ask him a few questions regarding his life’s work.

It’s been noted that celebrated architect William Smalley knew from a very young age what he wanted to do. I would argue that this early enchantment – this innate sense of a calling or a life’s work – appears to have shaped his designs in ways elusive to others among his profession.

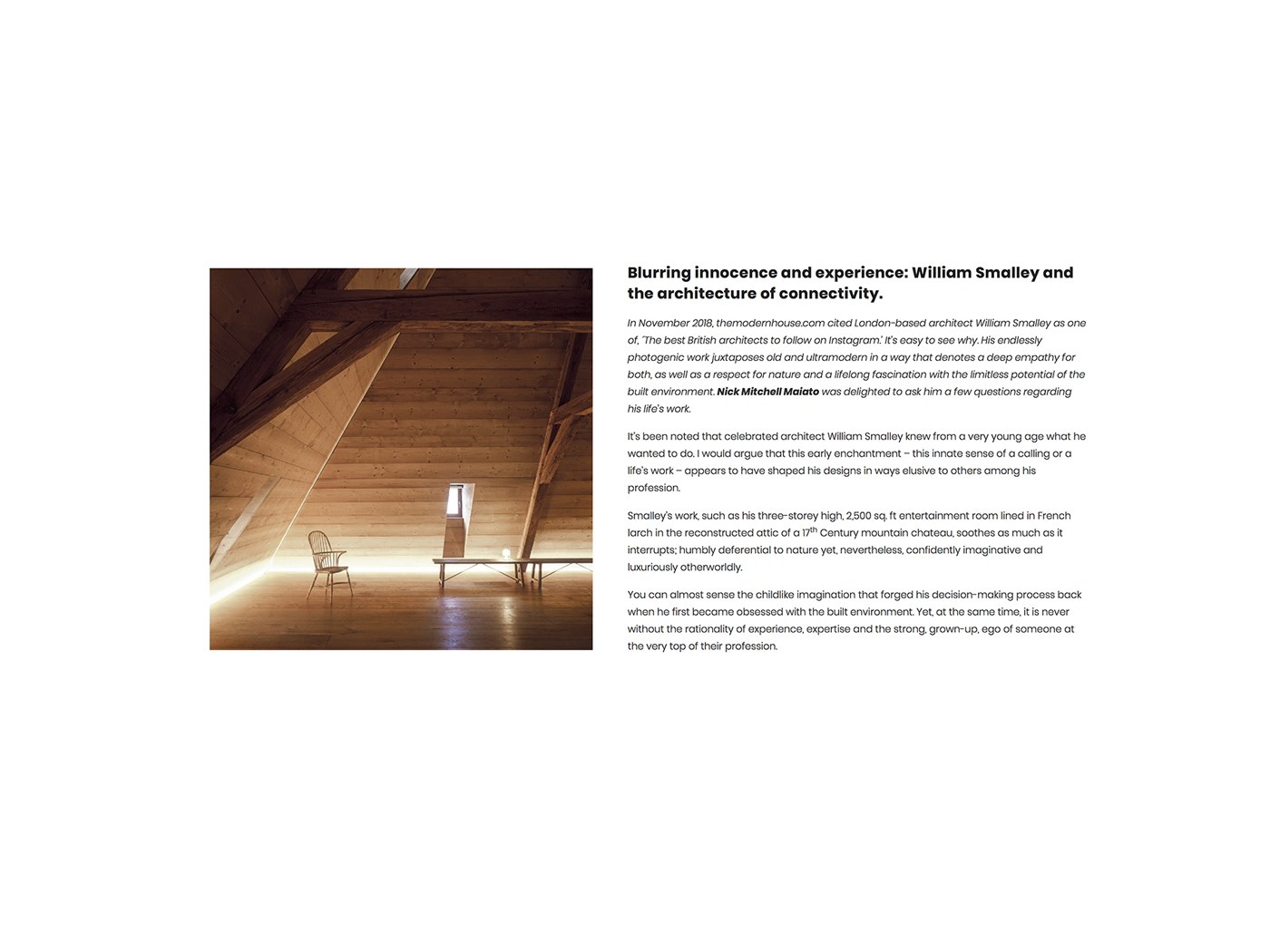

Smalley’s work, such as his three-storey high, 2,500 sq. ft entertainment room lined in French larch in the reconstructed attic of a 17th Century mountain chateau, soothes as much as it interrupts; humbly deferential to nature yet, nevertheless, confidently imaginative and luxuriously otherworldly.

You can almost sense the childlike imagination that forged his decision-making process back when he first became obsessed with the built environment. Yet, at the same time, it is never without the rationality of experience, expertise and the strong, grown-up, ego of someone at the very top of their profession.

You’ve only been running your own firm since 2010. To what do you ascribe the speed of your ascent?

“Architecture is a slow game and to me it feels like I’ve only just started, but it has probably helped that I’ve known what I wanted to do from the age of about eight, when one evening at the kitchen table there was a man introduced as the architect who was designing an extension to our house. I looked at his plans and I knew that they were what I wanted to do.”

Where did you grow up and how did it impact upon your interest in the built environment?

“We moved into my childhood home on my third birthday, and, perhaps as if my birthday present, I formed a bond with it that day. It was an old timber-framed house, with a barn attached on one side, in a village south of Oxford.

“As a teenager I wrote the entry in the book Crap Towns on our local town Didcot (it came nineteenth), and its crapness (especially set against Oxford’s otherworldliness in the other direction) did perhaps hone my critical faculties from a young age.

“Our house was partly fifteenth-century, which skewed my sense of what counted as old, and I suppose its fireplaces you could sit inside, its sloping floors, and beams you had to duck, made me aware that spaces have character, and through that character feelings.”

You studied at the University of Edinburgh. Did the Scottish landscape inspire your style (which has been described by some as ‘monastic’)?

“My monastic ideal is in a warm climate. I predominantly remember Edinburgh as cold. I wasn’t a rich student and didn’t have the money to head off for weekends in the Highlands, so if anything struck a chord it was the romance of Edinburgh’s skyline, and living in palatial Georgian apartments in the New Town, which we were aware would never again be equalled in scale, even if you did have to keep your coat on for dinner.”

Your ‘Mountain Chateau’ project is a stunning example of your development as a practitioner. You had quite a multi-faceted client brief, I believe. Can you tell us how you approached it?

“The project was the reconstruction of the attic of a 17th-century stone chateau in the French Alps, a single space 2,500 sq. ft in area and three stories high. The clients commissioned the project not because they needed the space, but simply because even in its unconverted state, it was too amazing a space to leave alone.

“So, the space came first and the programme second. It might host a chamber recital, become a venue in the town art festival, hold a dinner for 40, or a winter game of badminton when snowy outside. For all these uses, the criteria was large, uninterrupted space, and the new structure improved on the original so that it has no columns. More prosaically, there is a screening area in one corner that would fill any normal room, and beds that can be wheeled out and plugged in to sockets in the floor allow it to double up as a teenage party dorm. The roof of an adjoining medieval tower provided space for a shower room.

“Rather than eaves cupboards, two freestanding stacks, inspired by the local method for drying timber, house a kitchenette and a furniture store, and have a transparent quality so as not to interrupt the space, and allow the perimeter of the room to remain free.

“Lighting is key to providing flexibility, and also to making the space feel intimate.”

You completely rebuilt the timber structure of the attic, but seemed to be inspired to a degree by the light let in by the ruins of its predecessor. The room is flooded in natural light from all angles. This is an artful, and incredibly ‘meta’, example of the old clashing with the new. How much does the state of the building at the time you first experience it impact upon your design decisions, in general?

“I don’t think in terms of old and new, but of a continuity.

“A few years ago, my village school headmaster, by then retired, was shown a magazine article about me and my flat, in which I mentioned that he had bought me a copy of the Architectural Review when I was 10 (I spent every lunchtime and games lesson inside, designing houses). Having looked at our website, he wrote to me saying that he could see an intuitional continuity from those drawings when I was 10 to my work now, which was an incredible thing to hear because I think at base we have only our intuitional instincts to guide us (there is no such thing as an entirely rational response to an architectural brief), and I very consciously try to keep in touch with my intuitions and not stifle them, and to be open to everything a site or building has to reveal.

“I recall seeing the chateau attic for the first time, and the sense of delighted awe coming up the corner stair into the cathedral-like space; the particular smell and atmosphere of dry timber; and the indirect daylight glowing up from the open eaves around the perimeter.

“All of these sensations have been recreated in the new space. It was immediately obvious to me that the new space should be timber, now perhaps the strongest impression of the finished project, but it took quite a lot of convincing for the clients who assumed an attic would be plastered and were worried timber would be dark.”

You bring a subtly grandiose quality to otherwise very secluded and austere environments. Your Oxfordshire Farm project, for example, adds real drama to the bucolic landscape without extinguishing its tranquillity. Is the greatest measure of a building’s success its ability to somehow make us better realise our sense of peace by paradoxically disrupting it?

“I’m often struck how a building in a landscape can be the entire focus of your view – but that if you try to photograph that view, the building is insignificantly invisible. If you think of a monastery in a valley in France, tiny in comparison to the overall landscape, and yet it becomes the focus of the entire valley, emanating, or reflecting back, peace from its walls.

“Building is a disruptive act, and we have become scared of marking landscapes with our buildings. We tend to want to hide them or ban them. But buildings give human focus and scale to a landscape, to help us understand our place in it.

“Placing a building is like placing a sculpture in a landscape. A building should necessarily be tied to the place where it is built – it shouldn’t be possible to disassociate one from the other.

“I don’t think of my work as intentionally disruptive, but, like a well-placed sculpture, it has the confidence of its rightness.”

The 600-year old Liscombe House in Buckinghamshire is, perhaps, one of your most daring projects. Would you agree? The reverence you felt for the space comes through loud and clear and, yet, your choice of materials in the kitchen and bathrooms, for instance, is, again, disruptively tranquilising. What materials did you use for these rooms and what inspired your choices?

“I wouldn’t have thought of Liscombe as daring, but perhaps that I wasn’t intimidated by the house and its history allowed us to make the interventions we did. An interesting fact of working on listed buildings is that the work you add is instantly listed. I was conscious of the next architect in a hundred years or so having to justify unpicking our work to the then conservation officer.

“The kitchen looks out across the central courtyard to a fourteenth century chapel on the other side, and the slabs of marble at its end, and on the island counter, perhaps recall an altar. It took some persuading not to use a quiet white and grey marble, and I’m glad we prevailed.

“The vaulted master bathroom required a new roof to house it, so was quite an undertaking, I think justified by the space created. You step down into it from the bedroom, which brought to mind Roman baths, and so vaults and a timeless, monumental simplicity.”

You state on your website that the Thermal Spa in Vals, Switzerland by Peter Zumthor is, ‘Quite simply the purest expression of architecture of recent times.’ The symmetry of the Spa walls in the still water, and the aesthetic nod to a mountain-bordered body of water, celebrates the awesome glory of nature, much as I believe your work attempts to do the same. If not in a building, how might you express the pure goal of architecture in words?

“Nature will always be more complex and inventive than we could ever design for ourselves. There are valleys in Dorset whose beauty of form will always exceed any artwork created by man.

“An appreciation and awe of nature helps, I think, in life as well as architecture. By an understanding of nature, we provide buildings that shelter us but, in letting ourselves be moved by nature, we make architecture.”