ii 22

Lunuganga

Sri Lankan architect Geoffrey Bawa (1919-2003)’s country house and garden, Lunuganga, salt river, sits across a promontory into the Dedduwa Lake, an offshoot of the Bentota river in south eastern Sri Lanka.

By my reading, Bawa was a simple, complicated man – son of a wealthy barrister, with colonial and local roots, 6‘4“ tall in a country where, well, that is not the norm, he studied English at Cambridge in the 1930s, passed the bar, drove a Rolls-Royce, and bought the land at the (young, to me) age of 28, and then returned to the UK to study architecture at the AA (much of his time spent in fact in Rome, returning for crits in the Rolls), a career he commenced at the age of 38. Which confirms my theory that architecture is a slow game.

I was told by someone who had worked with him that he was shy and gentle, ‘Damn and Blast’ his worst outburst, followed by silence, though he was evidently also determined: he became the most influential architect of the Sri Lankan independence era, establishing the profession in a country where one didn’t exist.

Lunuganga was clearly his refuge. Well, one of them. His townhouse, No.11, 33rd Lane in Colombo, is, but for the roof terrace, entirely inward-looking, focused around courtyards. Lunuganga is expansive. It feels on the scale of a giant estate, though is in fact a garden of just twenty or so acres. The tangible sense of space and scale is not accidental, but achieved with a careful and judicious eye.

Bawa’s architecture, from what I saw of it, is a mix of sensitivity and pragmatism, always attuned to its place. It doesn’t sweat the small stuff or set itself impossible tasks, but rather it seeks, and attains, a sense of generous ease and inevitability – making even a hotel built against a cliff and covered in creepers in which monkeys play feel normal. And that same ease, inevitability and awe is true at Lunuganga.

He had swathes cut through the rubber tree plantation that surrounded the original colonial bungalow to reveal views out to the surrounding water which, as his name for the garden reveals and despite being outside its boundaries, is the essence of the place.

From the privileged spaces around the house, birds soar with you; nature is surveyed. There is an anecdote about a young architect being invited for Sunday lunch at Lunuganga for the first time and warned by Bawa that he would be chopping trees, so to take him as he found him. Expecting to find Bawa sweating with axe in hand, the visitor was surprised to meet him on the terrace, with a gin and tonic in one hand and megaphone in the other, directing the gardeners’ cutting of trees from afar. Nature held at one remove.

It all feels incredible yet inevitable. The large grid set into the north terrace lawn outside the house, bold yet so subtle it hardly registers consciously, extends the house outdoors and fixes the pivotal frangipani tree into the composition. This tree – in fact two grafted together, its branches weighed down to spread its bows – is the fulcrum around which the whole garden pivots, and to which your heightened sense of space is tied.

It is telling that this centre is outside – the house’s internal spaces, though beautiful, are secondary; they serve the garden rather than the other way round, in this place where life is lived outdoors.

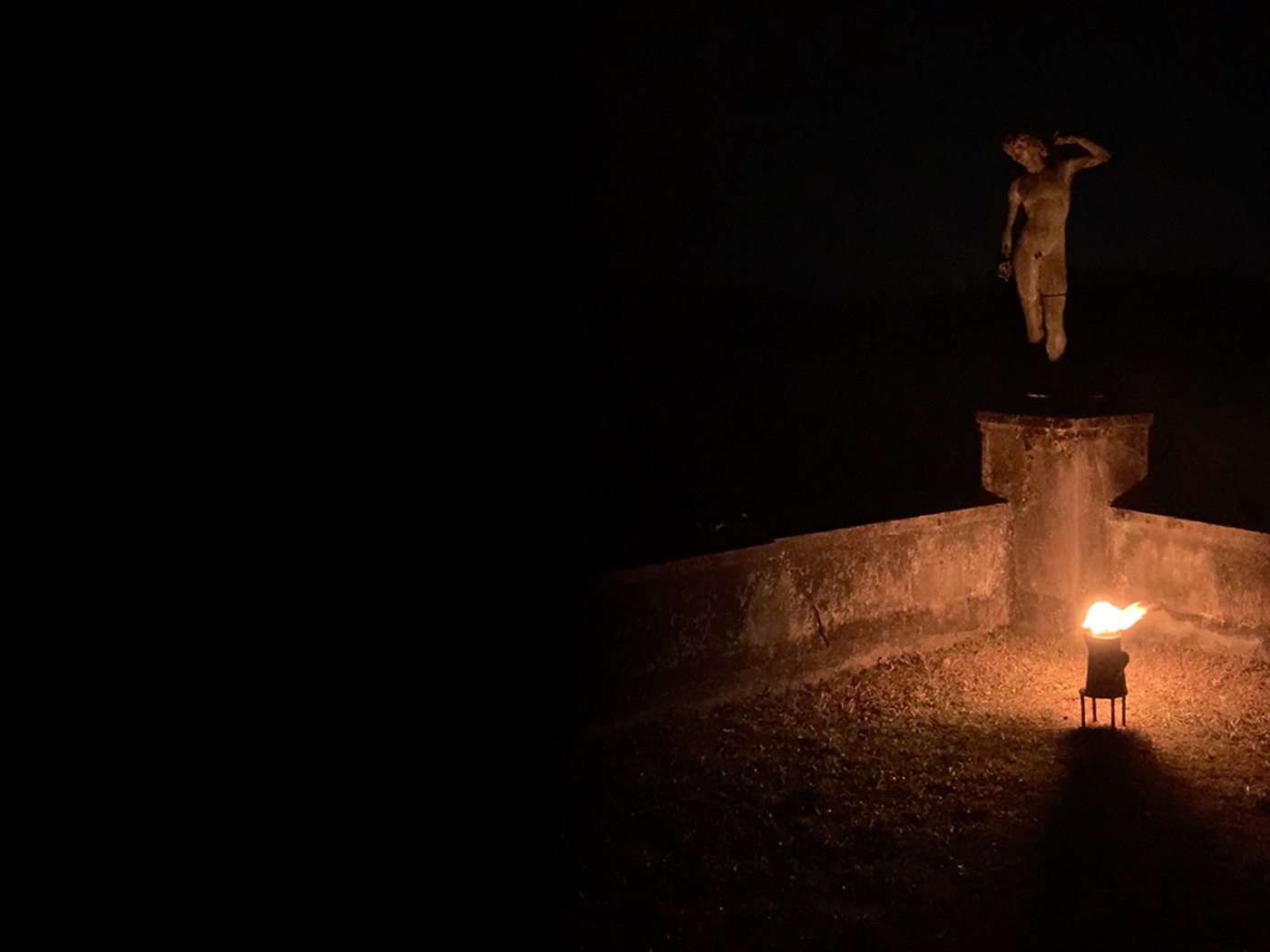

I want to mention the baroque curlicues of the terrace embankment edge, unexpectedly perhaps my favourite single element (in a garden where elements should not be extracted). Bawa’s time in Italy is felt. In fact the whole garden is a place in which Bawa’s well of references can be felt filtering through.

On the other side of the house, the lane to the neighbour’s property at the tip of the peninsula passed straight across the opened-up view. Bawa had it sunken, the gorge hidden by planting, like an English ha-ha, another reference filtered. Bawa had several feet taken off the crest of the hill beyond so that he could see the shimmer of the lake in the distance from his breakfast table, outside the front door of the house. I felt that you could sense this change, and perhaps to mask this Bawa placed a large pot under an old moonamal tree as the visible mark of man here. When the old tree fell shortly before his death, Bawa, by then half-paralysed by a stroke and unable to speak, shed a tear – his ashes would be buried under it. (A replacement tree was found to shelter him.)

Around and below the house, amongst trees, a series of outbuilding were built at the pace of roughly one a decade, placed at edges, forming and framing courtyards and terraces, providing living and work spaces, a gallery and guest room (and now each a wonderful hotel room, managed by Teardrop hotels for the Geoffrey Bawa Trust). The rooms are full of Bawa’s beautiful things. More references.

The house and north terrace sit fifty foot above the water. Below, designed to be seen from above, rice fields are graded by colour, darkening away from the house towards the dark lake. Down here giant lizards roam, and in the lake crocodiles swim.

Accompanying the descent to the water and a direct relationship with nature, are steps, stairs and seats. Often set against the hillside, making you conscious of the massive damp earth on one side and the heavy open air on the other, the steps, and the views from them, make you always aware of your height in the garden, and so always position you in the space; all are beautifully considered. Walking around, I found that at every turn Bawa provides a choice of path and route, which felt its own mark of generosity, never directing, always allowing freedom within his creation.

Time. There is physical space, and the space of time. The garden was conceived and developed over the space of fifty years. It was always a place of flux. Bawa recognised that it was a continuous dialogue with nature; the voracious jungle would eat it in a matter of wet seasons if it were left untended.

To be in the garden it to be conscious of space, of time, of movement, of nature, of self. The gardeners’ sweeping of the gravel feels part of the creation.

Lunuganga was an out-of-body, life-enhancing experience. It is a personal, indulgent, creation, but felt universal and elemental. I cannot deny, I would like my own.