i 20

Have Less Stuff

A note on Picasso’s clutter. If his attention alights on some curio, he recognises the life in it. He salutes it as a precious seed of information and intention.

Julian Bell, Royal Academy of Arts Magazine, Winter 2019

My flat is overflowing. Or feels like it (friends point out that it isn’t, and that all is relative, but).

A pile of filing. I am not one of life’s filers. Leave it long enough and it can be chucked, though the ideal is having nothing to file in the first place. It moves around by itself from time to time.

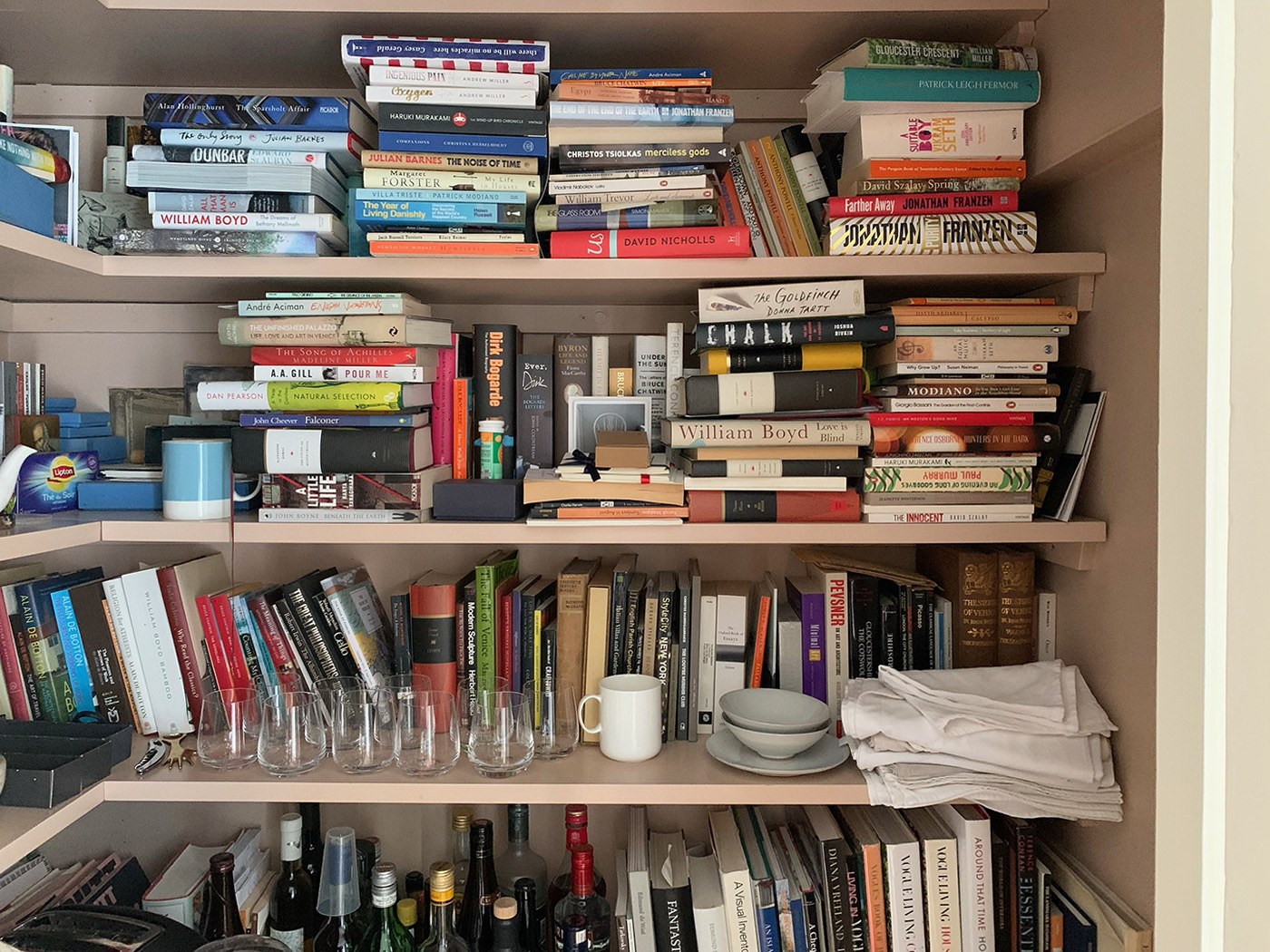

Books. They multiply. I gave up the rule that if a book is bought it is started, and if started it is finished. This used to successfully temper the habit. Now I flit, and they arrive unabated. Art boxsets double as side tables to justify their presence. Though leafed through they have no need to justify themselves: Julius Schulman’s photographs of sunny, optimistic Californian modernism to cheer English gloom; Lucien Freud’s delicate early portraits, belying a sensitivity it’s as if he was later embarrassed by.

Lights sitting on the boxsets, for guests sitting on low sofas and chairs. A pink chair for the terrace of my house in Majorca. That I don’t own.

Pictures. Not many. Acquired sporadically, without forethought. Dispensed with sporadically. Leaning against the walls from the floor, non-committal, guests in the room.

Other slighter objects. Postcards as memento mori, two of each, one to send and the other to keep. Sunglasses cases for lost (or just mislaid?) sunglasses. A bag with a present to take back to the shop, left out not to miss the 14-day return period.

Dog toys, massacred. Dylan’s presence (he of the four legs) is limited to his few toys, ugly before they were decimated, but easily thrown out of sight behind the sofa. His presence also in the always dimpled cushion from his mid-hop up onto the back of the sofa, from which he can often be seen from the street outside surveying impassively.

The forlock of a Venetian gondola, sculptural in form like the crumpled cushion. Should this have left Venice, patched up and careworn though it is?

Architectural models. The least domesticated, yet the easiest to live with, the least pressing.

A piano. Did I mention the piano? There is a grand piano, craned in with inches to spare through the windows (it would have crushed the fragile stairs even if it had navigated the chicane in the hall). The piano is too big and fundamental to count as clutter. It achieves gentleness in other ways. It was voiced, which is to say the felt of each key hammer and damper was plucked with a hooked needle, to achieve the right softness of sound to suit the room, and neighbours. And the music played on it is gently paced, limpid. It has an oddly light presence in the room.

The collection of ceramics and maquettes sitting on top of it less-so. Ideally there would be nothing on its lid, even if it is laid shut in deference to neighbours. Bowls. One of matt celadon-glazed porcelain which spent 400 years underwater wrecked in the China sea, and yet now rings out as if a siren call. The frozen figure-of-eight of the whipped Rupert Spira bowl, fleeting poetry etched into its sides. A sole Edmund de Waal pot, a birthday present from when his craft had become art, but were yet installations of one. A plaster maquette by 60’s artist Fred Kenett. Each should have its own space to hold, their sole function to be held, not to be budged up together and forced into polite conversation they would really rather not be engaged in. When the palazzo comes good it will not be difficult to populate it. The Shipwreck Bowl Room. The de Waal Hall.

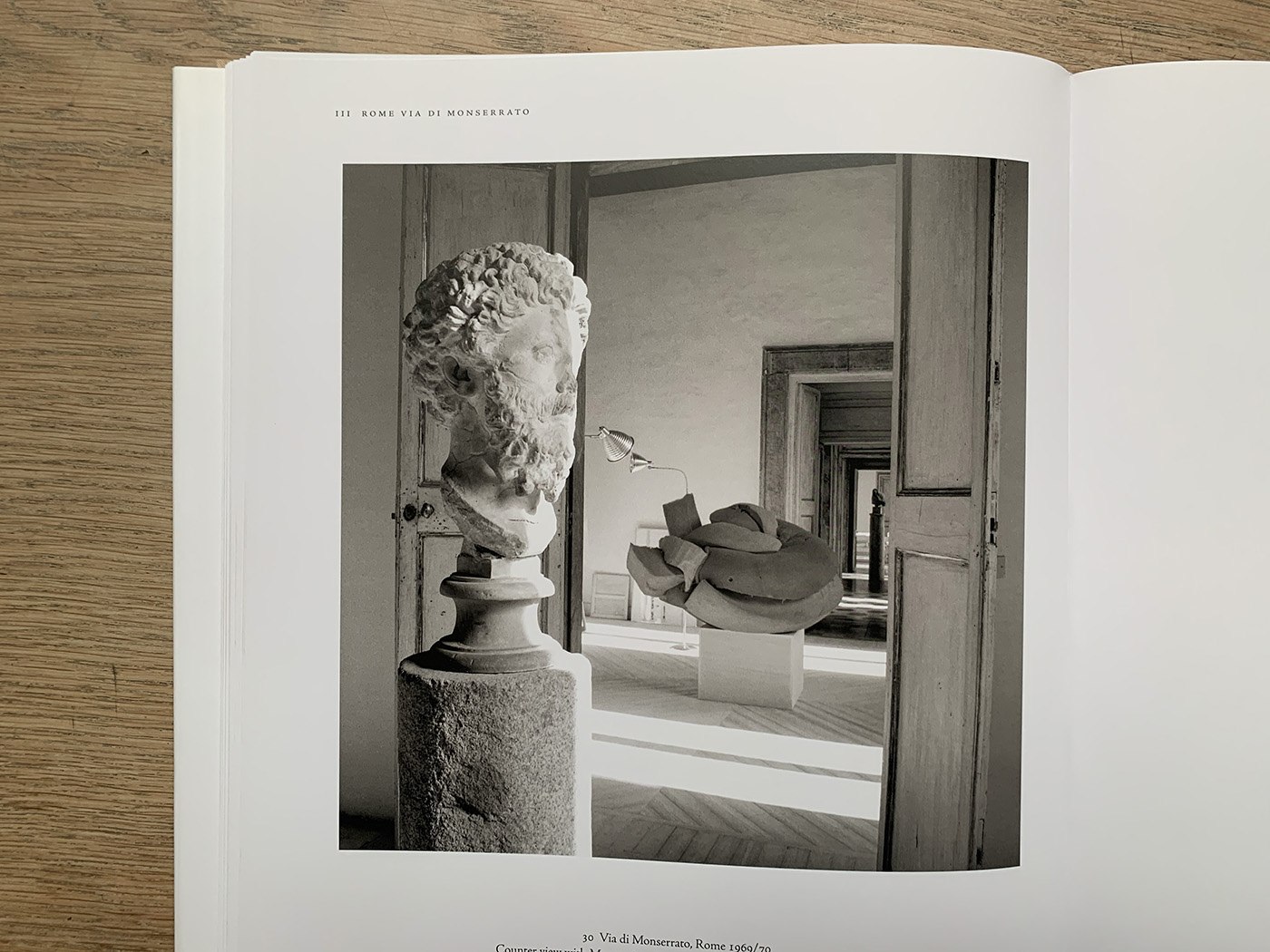

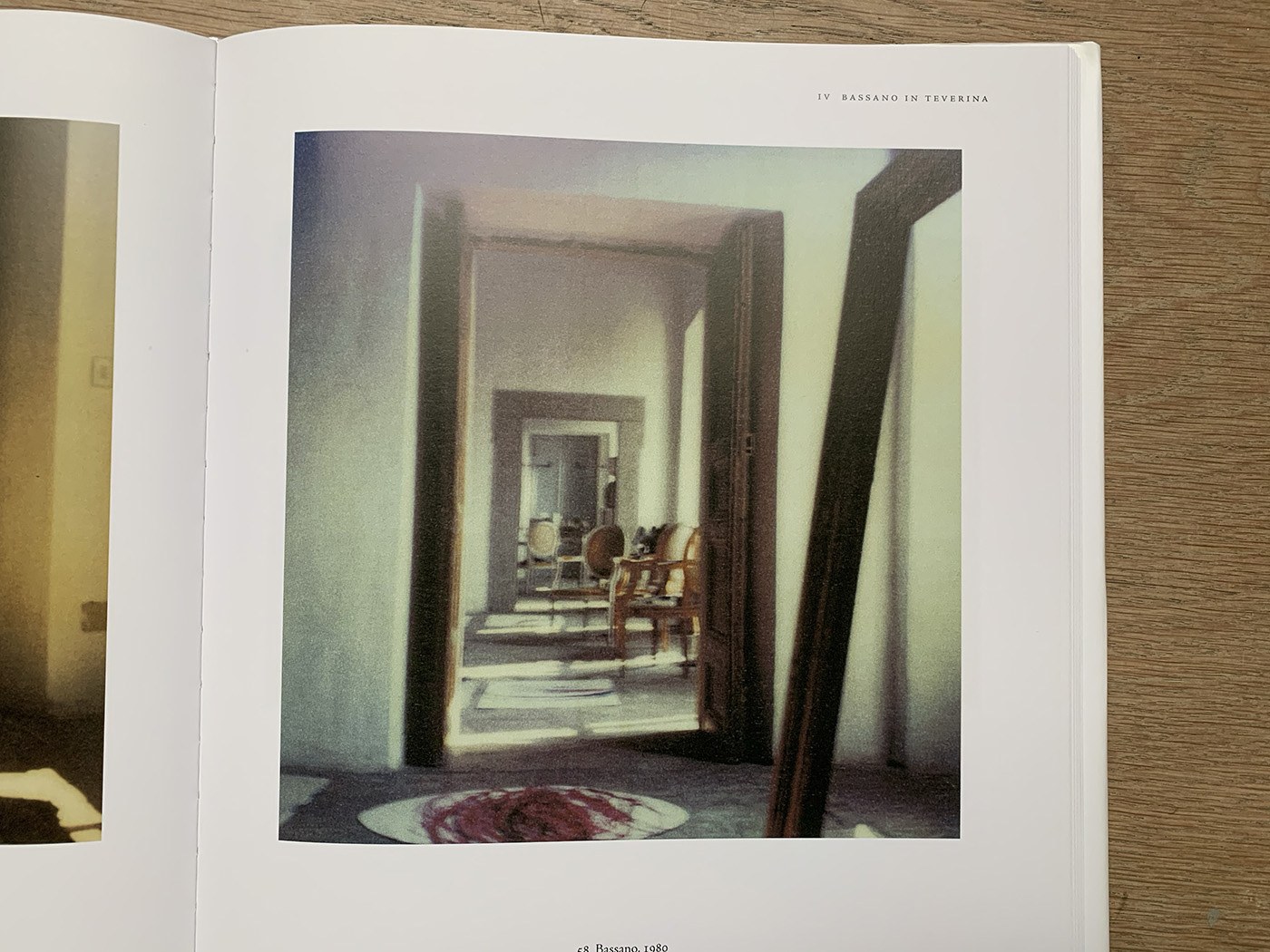

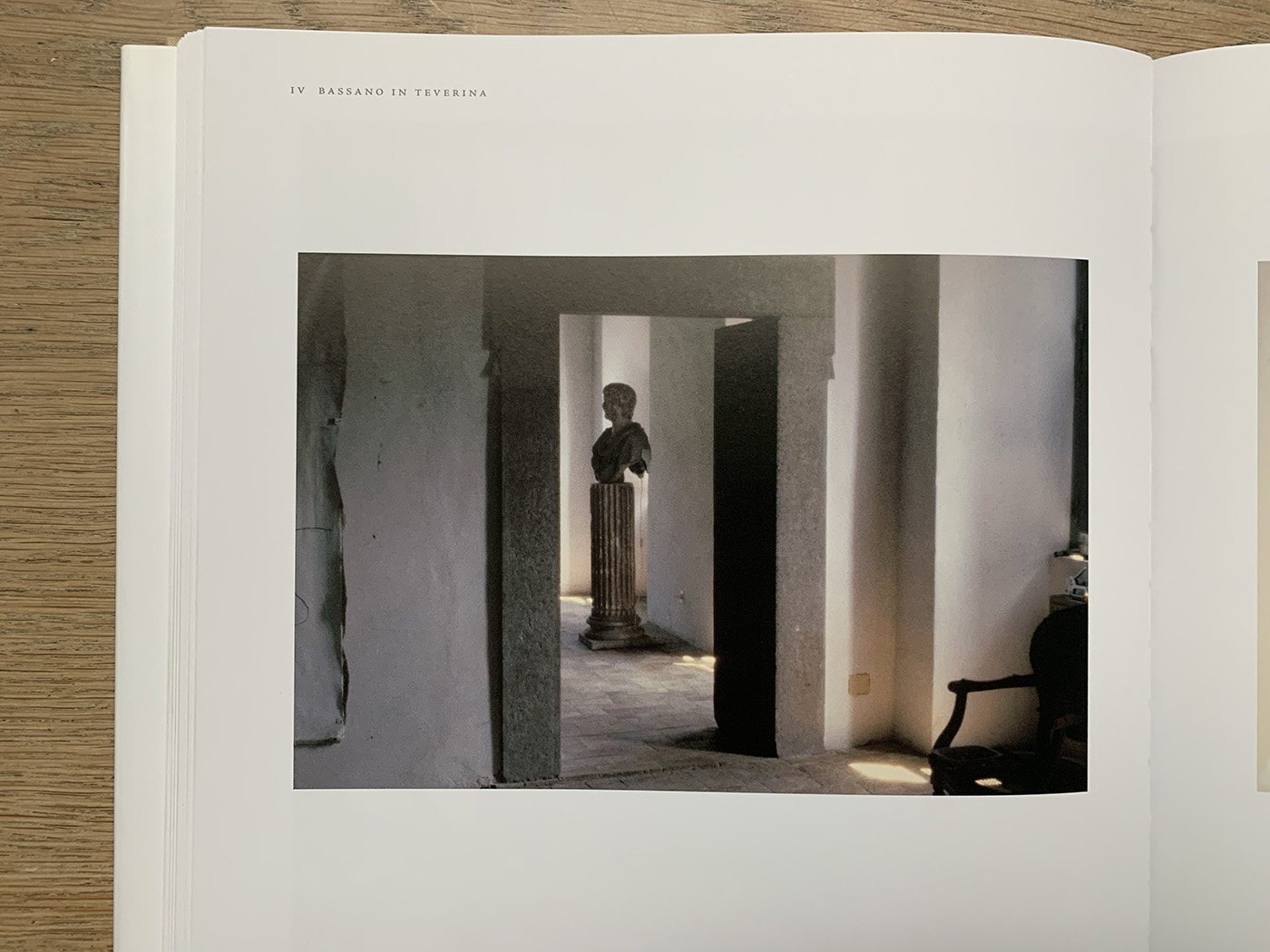

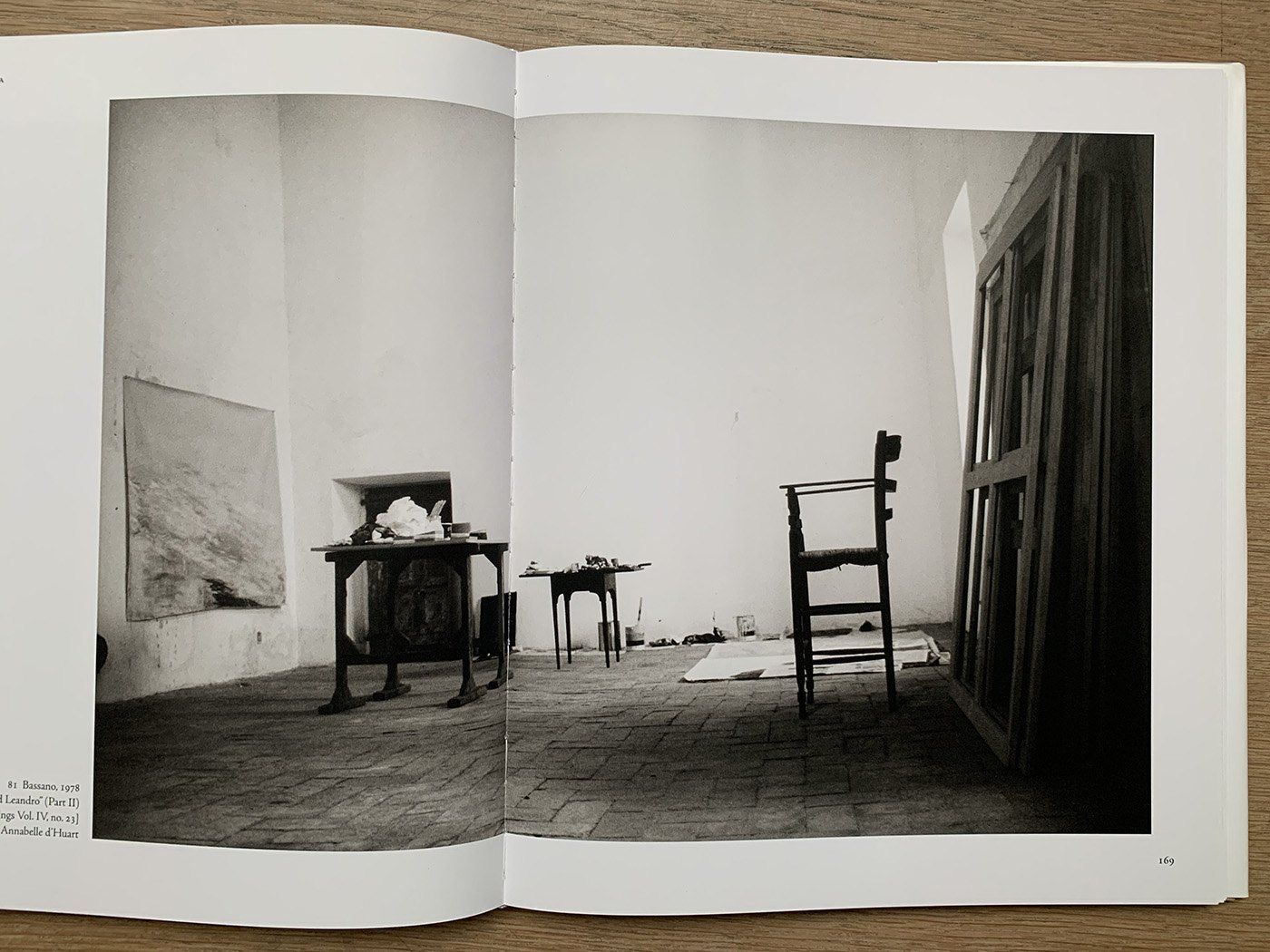

Cy Twombly had three palazzi, not that far apart, in Rome, Bassano in Teverina and Gaeta (Rome was just a palatial apartment, in a palace). To what degree is Cy Twombly’s art a function, the result, the twin, of the spaces it was made in? Could he have made the art without the rooms? Was his marriage to the money of Tatiana Franchetti itself a work of art – one of his greatest artworks? Rooms after rooms none of discernible function. Is heaven a Twombly palazzo? Whitewashed walls, matt, manifestly massive yet light of presence. Windows, or doors framed in blocks of stone, opening either to another room, and another, or out over sea way below.

He painted on canvasses nailed directly to the plaster walls, without stretchers, primed soft white indistinguishable from whitewash, a continuity of the endlessness of the plaster walls. Is this what gives his work its lightness, even when the subject is heavy? A freedom of intent, freed from frame. His sculptures seem designed to sit within his walls. They have the impermanence of the pictures on my floor.

Paints, paintbrushes, oil. The detritus of my nascent painting habit. Doing its best to dispel any notion of rest, of peace, of retreat. The canvasses themselves, settling into themselves, content or unsettled. Those in progress definitively uncontent. Speaking their disquiet, pressing their discontent, but rarely offering up an answer. Or suggesting a brave answer, from which it will not be possible to return. Brave or foolhardy? And the debris, half-used and squeezed-empty paint tubes, chosen for the label from Cornelissen’s, itself chosen for the gentleness of its kindly undulating floor and staff. Beautiful as the by-product of a search for beauty will be. Laid aside, revealing the bloody crimes frequently committed here, traceable from the painting through the flat to the sink, where attempts at eradicating the evidence is unconvincing.

My living room, the palazzo.

Seeds of intention. Nothing is accidental; nothing is here accidentally. All come with intent, whispering as they arrive: Have Less Stuff.

Happy New Year.