v 18

The New Craftsmen

The story of the Craft House written for The New Craftsmen, May 2018

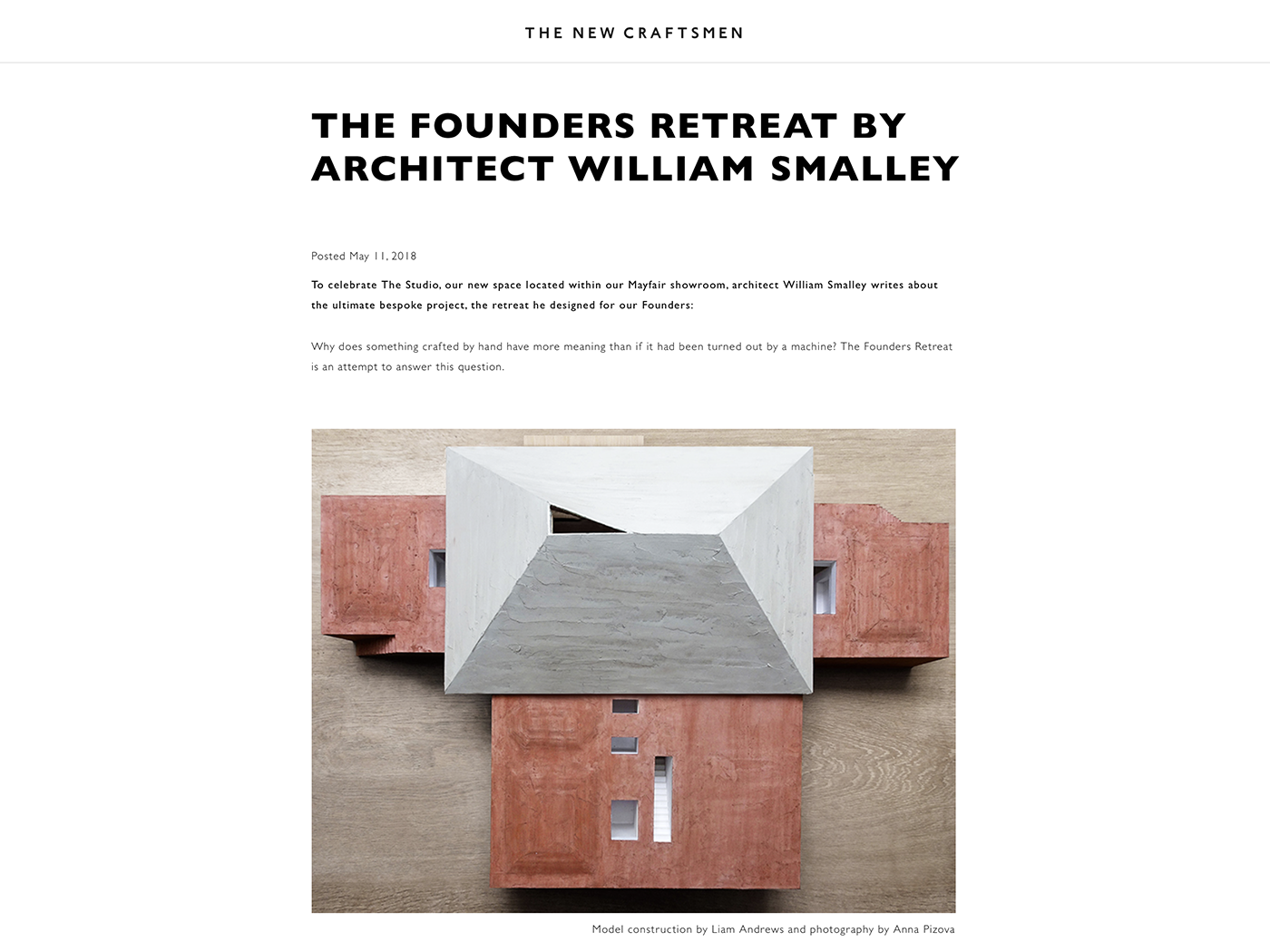

Why does something crafted by hand have more meaning than if it had been turned out by a machine? The Founders Retreat is an answer to this question.

We are apt to ask the wrong questions: What is the cheapest set of plates I can bear to live with? instead of What is the best possible plate, one that will give me pleasure every time I use it, that I will remember after it is gone or have with me for the rest of my life – what plate, even, will outlive me?

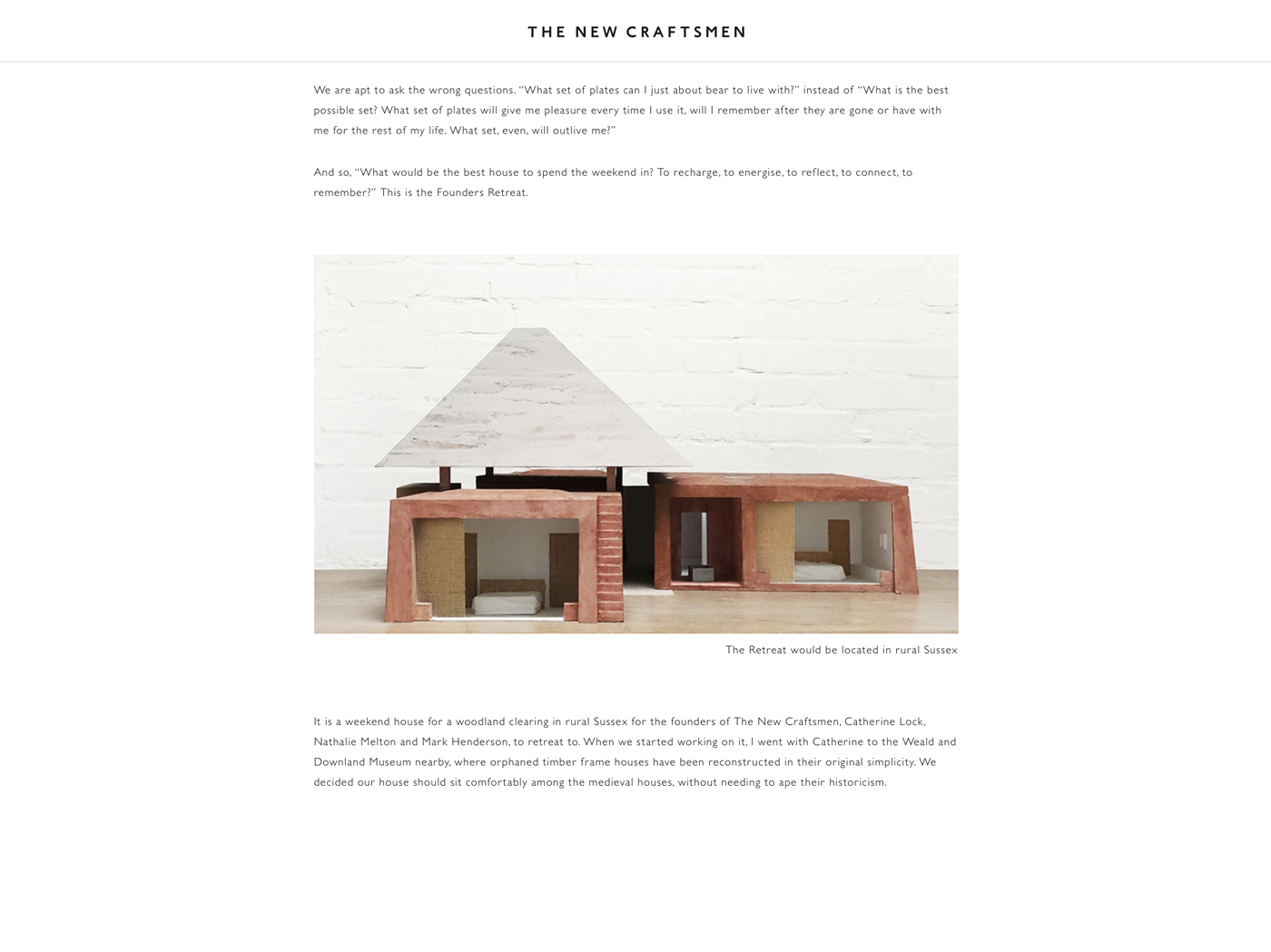

And so What is the best house to spend the weekend in? To recharge, to energise, to reflect, to connect, to remember – this is the Founders Retreat. It is a house for stories to be told, to be made – and whose inventory would make a storybook in itself.

A weekend house for the founders of the New Craftsmen, Catherine Lock, Nathalie Melton and Mark Henderson, to retreat to, in a woodland clearing in rural Sussex. When we started working on it, I went with Catherine to the Weald and Downland Museum nearby, where orphaned timber frame houses have been reconstructed in their original simplicity. We decided our house should sit comfortably among the medieval houses, without needing to ape their historicism.

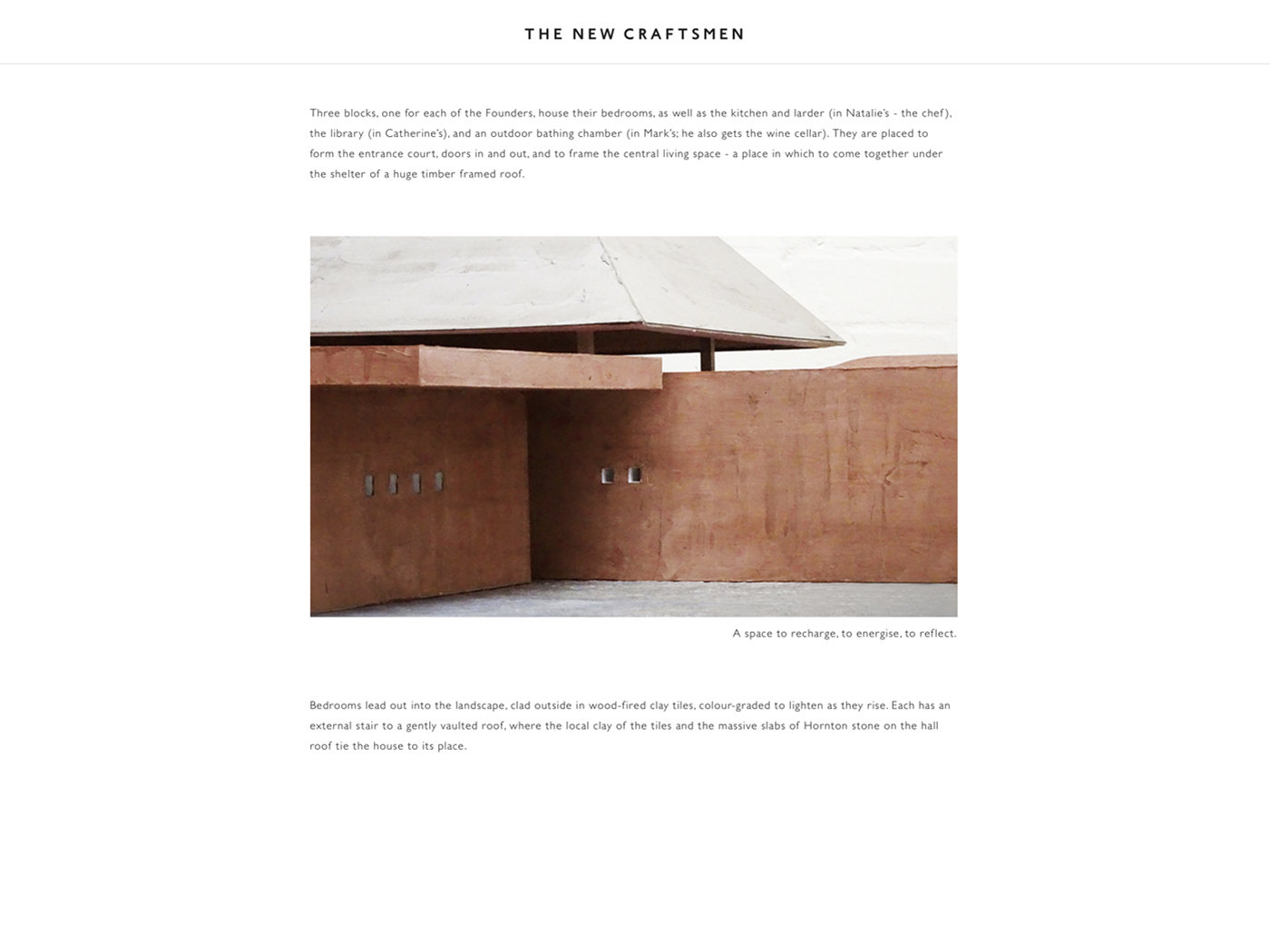

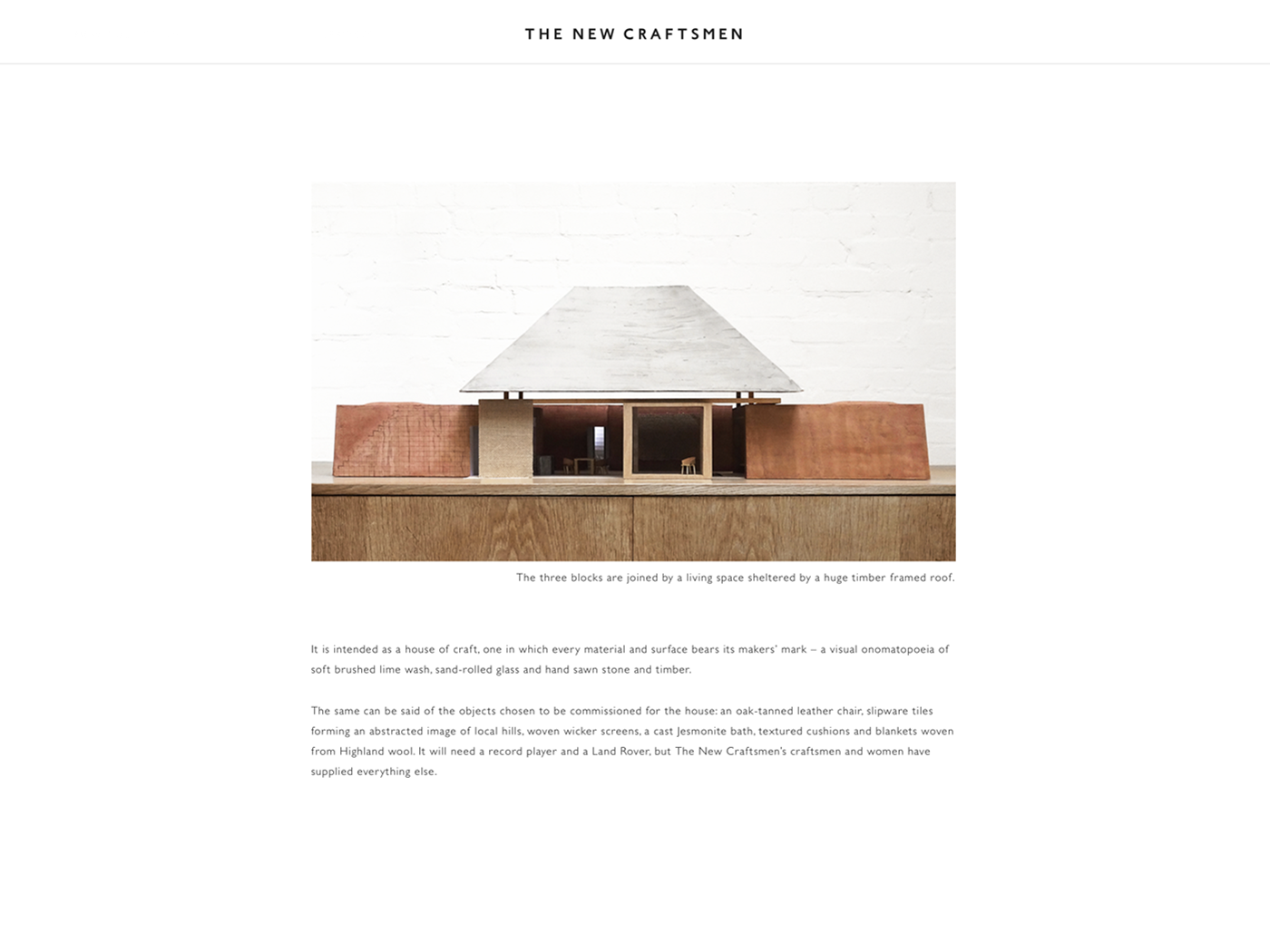

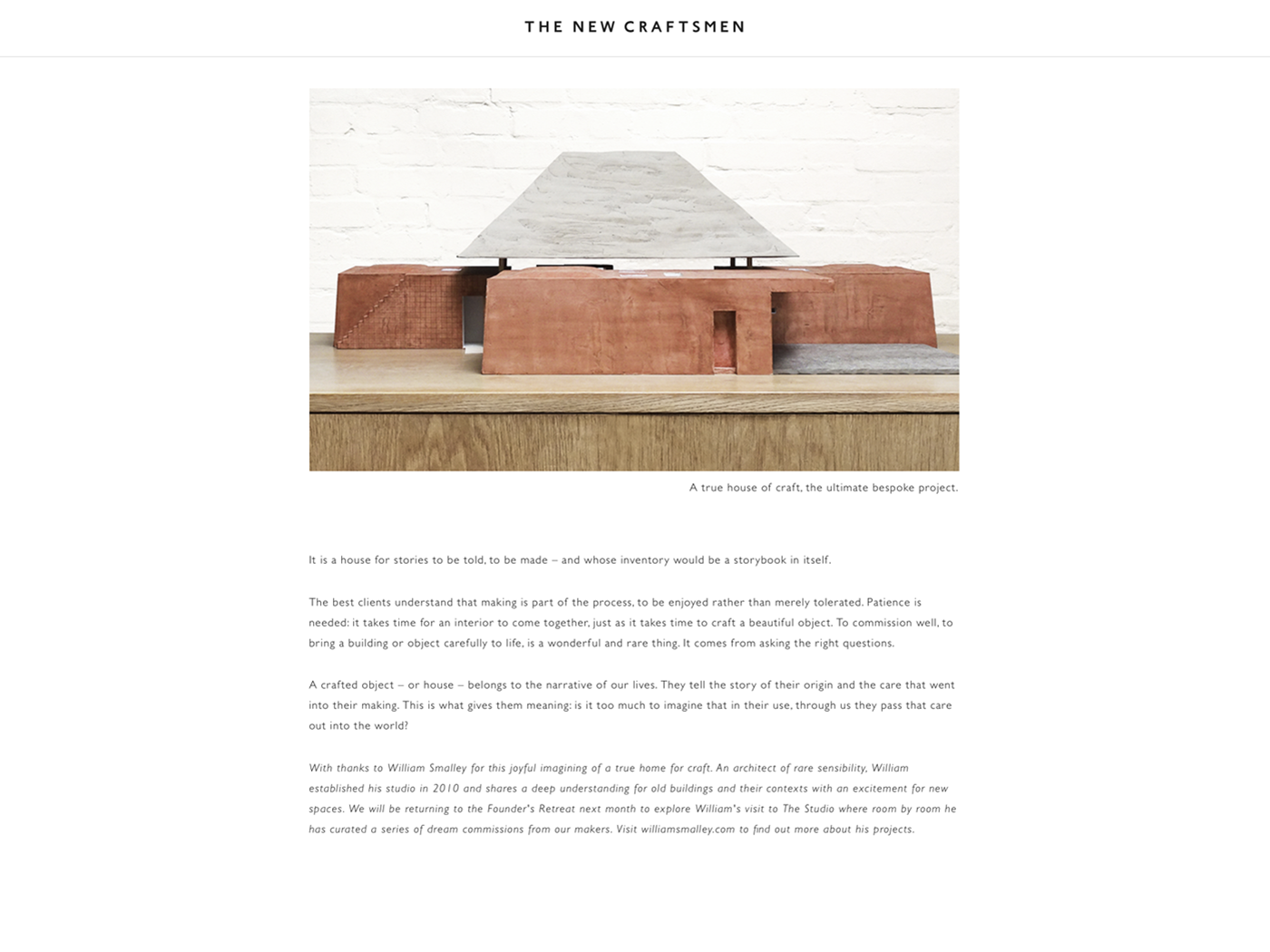

Three blocks, one for each of the Founders, house their bedrooms, opening out to the landscape and also housing the kitchen and larder (in Natalie’s, the chef), a library (in Catherine’s), and an outdoor bathing chamber (in Mark’s; he also gets the wine cellar). They are placed to form the entrance court and front door, and to frame the central living space – a place in which to come together, like a medieval hall (meets ‘70s conversation pit), sheltered under a huge timber framed roof.

The bedroom blocks are clad outside in wood-fired clay tiles, colour-graded to lighten as they rise. Each has an external stair to a gently vaulted roof, recalling the house in Luca Guadagnino’s film A Bigger Splash on the southern Mediterranean island of Pantelleria, and hoping perhaps to bring some southern sun to rural Sussex.

The local clay of the tiles, and the massive slabs of Hornton stone on the Hall roof tie the house to its place – and so to all the histories of the place.

It is intended as a house of craft, one in which every material and surface bears its makers’ mark – a visual onomatopoeia of soft brushed limewash, sand-rolled glass and hand-sawn stone and timber.

The same can be said of the objects chosen to be commissioned for the house: an oak-tanned leather chair in which to drink whisky, slipware tiles forming an abstracted image of local hills in the kitchen, woven wicker screens to shade sunlight, a cast Jesmonite bath, textured cushions and blankets woven from Highland wool. It will need a record player and a Land Rover, but otherwise the New Craftsmen’s craftsmen have supplied everything else.

Years ago, when I was moving into my first house and carefully choosing each ladle and teaspoon, a friend said You can’t have everything perfect, to which I thought Why not? It should be self-evident, simple beyond simple, to have things around you that you like. I used to have narrower tastes, and so fewer things, which helped. My tastes have broadened, and so has my inventory.

There is a Chinese proverb Let your boat of life travel lightly lest your possessions sink you. Mine now number a grand piano, so I guess I’m sunk, but I have a relationship with all my possessions; I know them all.

You can tell nice people from their objects, and the interiors I like are not the most outwardly perfect but those that most reflect their owners. But once surrounded with beautiful and personal objects, the great thing is not to be precious about them, even, or especially, if they are precious. Used and enjoyed, having beautifully crafted objects around you elevates the everyday. It is a way of escaping the rat race without having to give up your job and nice holidays.

To commission well, building or object, to cause it to be brought carefully to life, is a wonderful and rare thing. It results from asking the right questions. Though patience is needed: it takes time for a house to come together, just as it takes time to craft a beautiful object. The best clients understand that making is part of the process, to be enjoyed rather than merely tolerated: architecture is not found, it is made. Watching builders solving problems on site is one of the great pleasures of my job.

Crafted objects – or a house – belong to the stories of our lives. They tell the story of their creation, and hold the care that went into their making – is it too much to think that, as we use them they pass that care out into the world?

Seemingly inanimate objects telling stories and nurturing: it is this that gives them meaning.