ix 22

Design Anthology III

London Modernism featured in design anthology uk 12 September 2022

Modernism Renewed

Even the finest examples of mid-century modernism rarely survive the ravages of time unscathed. Although one can always admire the slender structure and expansive glazing of a post-war house, these qualities do not always translate into comfortable, economically viable places to live. Sympathetic refurbishment and restoration must tread a fine line between preserving original features and making spaces fit for the future.

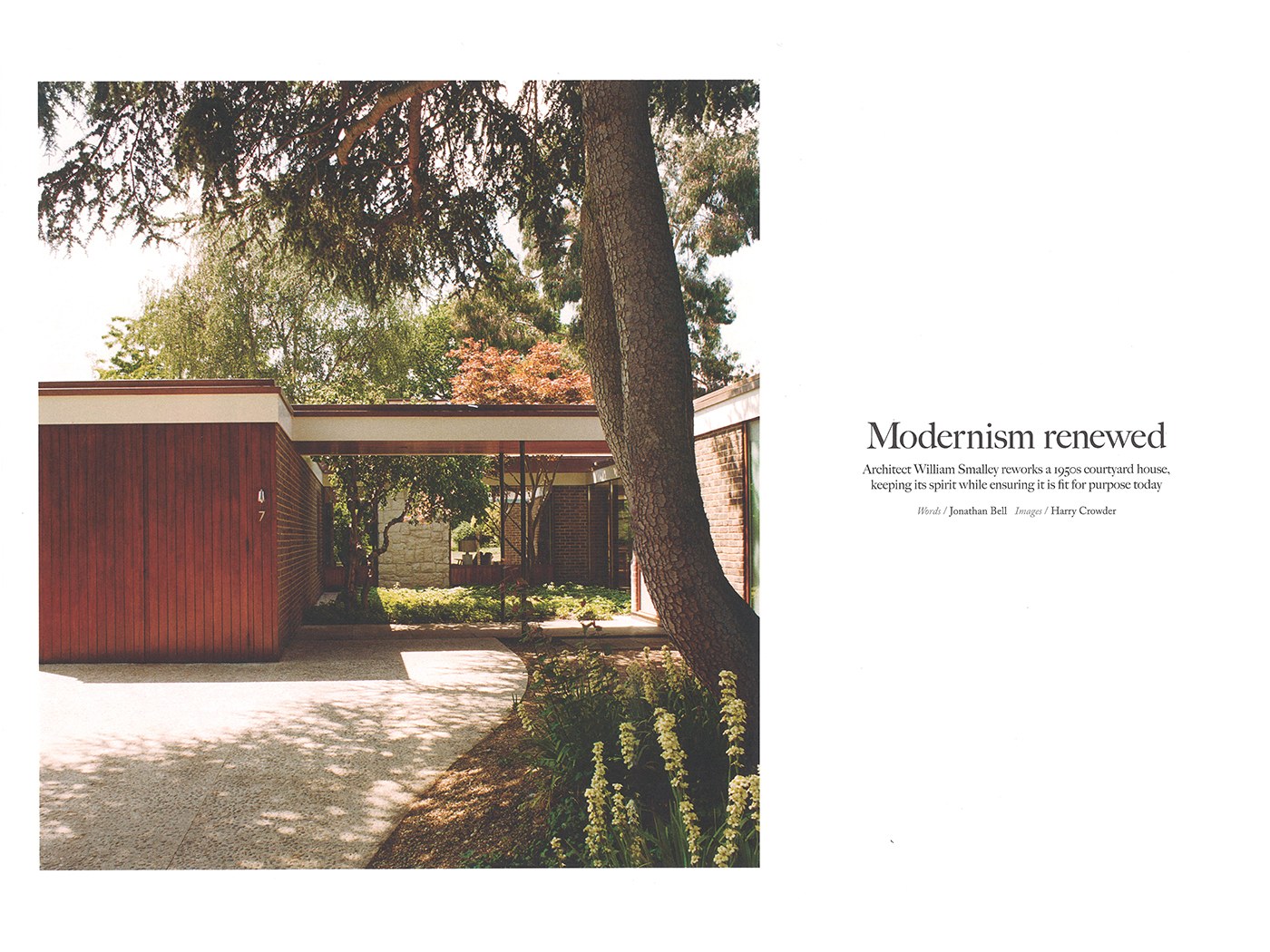

This 1950s house in south-west London was a classic example of a property in need of an overhaul. Built adjoining a Span estate, one of the pioneering groupings of post-war housing overseen by the architect Eric Lyons, the house occupies a plot reserved for slightly larger detached houses on the development. The single-storey courtyard house was designed by the architect Leslie Gooday in 1958 and then extended a few years later. Gooday, best known for his work on the Festival of Britain, designed several richly detailed private houses in the south east. Until the current owners acquired it, this particular example had been in the same ownership ever since it was built.

Although the house is locally listed as a building of historic interest, the planners were initially sure that “no one would care” what happened to it, says architect William Smalley. However, as he recalls, “on the day that we were due to get approval, the conservation officer blocked [the project].”It turned out that not only had she not been informed of the proposal, but she was also the enthusiast who had flagged the house’s design quality in the first place. “However, when she saw our scheme she realised we were being very sympathetic, and it improved as a result,” he adds.

The most substantial change is the addition of a first-floor master bedroom. “When I first visited the house, I went up on to the flat roof to check its condition,” says the architect. “There were fantastic views across the common opposite, and I thought That’s what you’d want to wake up to.” Although the new storey – which only occupies a small percentage of the actual floorplan – was contentious, other physical alterations were shown to be in the spirit of Gooday’s original design. “We had his original drawings, which not only showed us that the house was riddled with asbestos, but that the shallow pitched roof facing the garden was intended to be copper, not roofing felt,” says Smalley. It was presumably omitted because of cost, but copper features in Gooday’s own house, the acclaimed Long Wall in St George’s Hill, so Smalley and his team, led by project architect Liam Andrews, had a precedent to use it on the new extension. “Copper only used to go green because of acid rain and smoke pollution,” says Smalley, “although you can get it pre-patinated, we’ve left it to weather naturally. It might never even go green.”

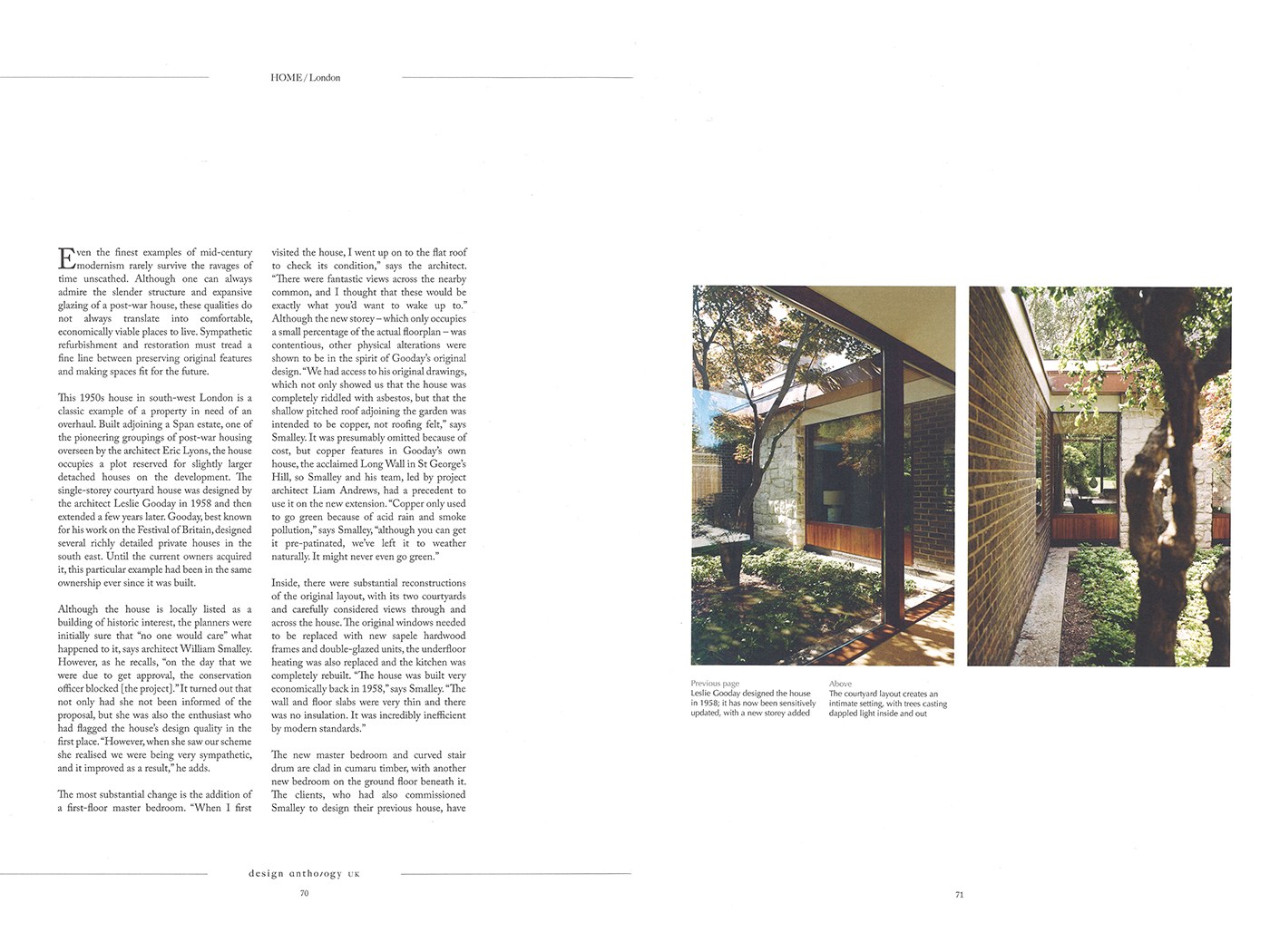

Inside, there were substantial reconstructions of the original layout, with its two courtyards and carefully considered views through and across the house. The original windows needed to be replaced with new sapele hardwood frames and double-glazed units, the underfloor heating was also replaced and the kitchen was completely rebuilt. “The house was built very economically back in 1958,” says Smalley. “The wall and floor slabs were very thin and there was no insulation. It was incredibly inefficient by modern standards.”

The new master bedroom and curved stair drum are clad in cumaru timber, with another new bedroom on the ground floor beneath it. The clients, who had also commissioned Smalley to design their previous house, have three young children, and the ground floor now sports three equal-sized ground floor bedrooms adjoining a playroom and family bathroom. One of the original courtyards is now a ‘play garden’, accessed and overlooked from the kitchen as well as the playroom.

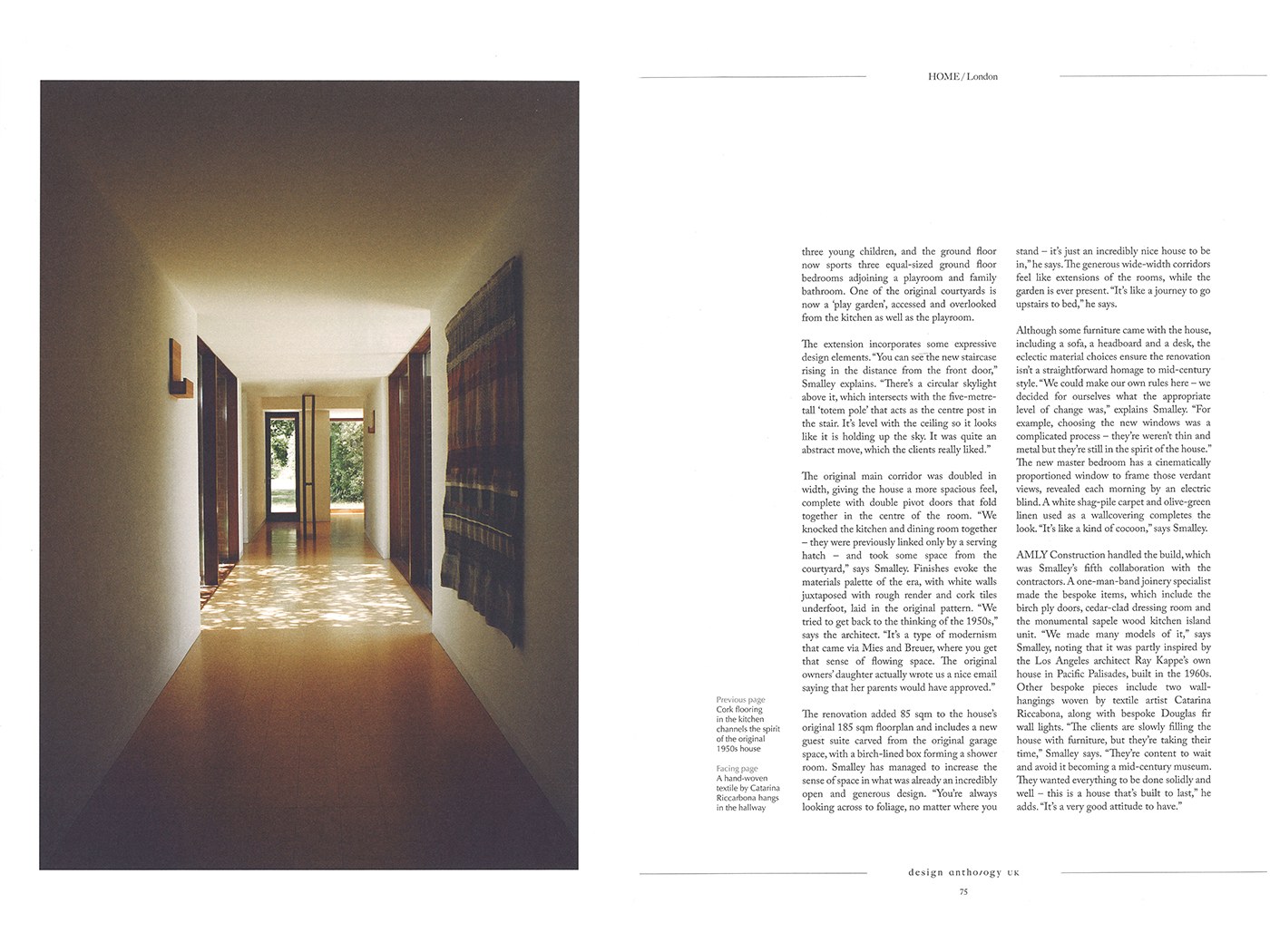

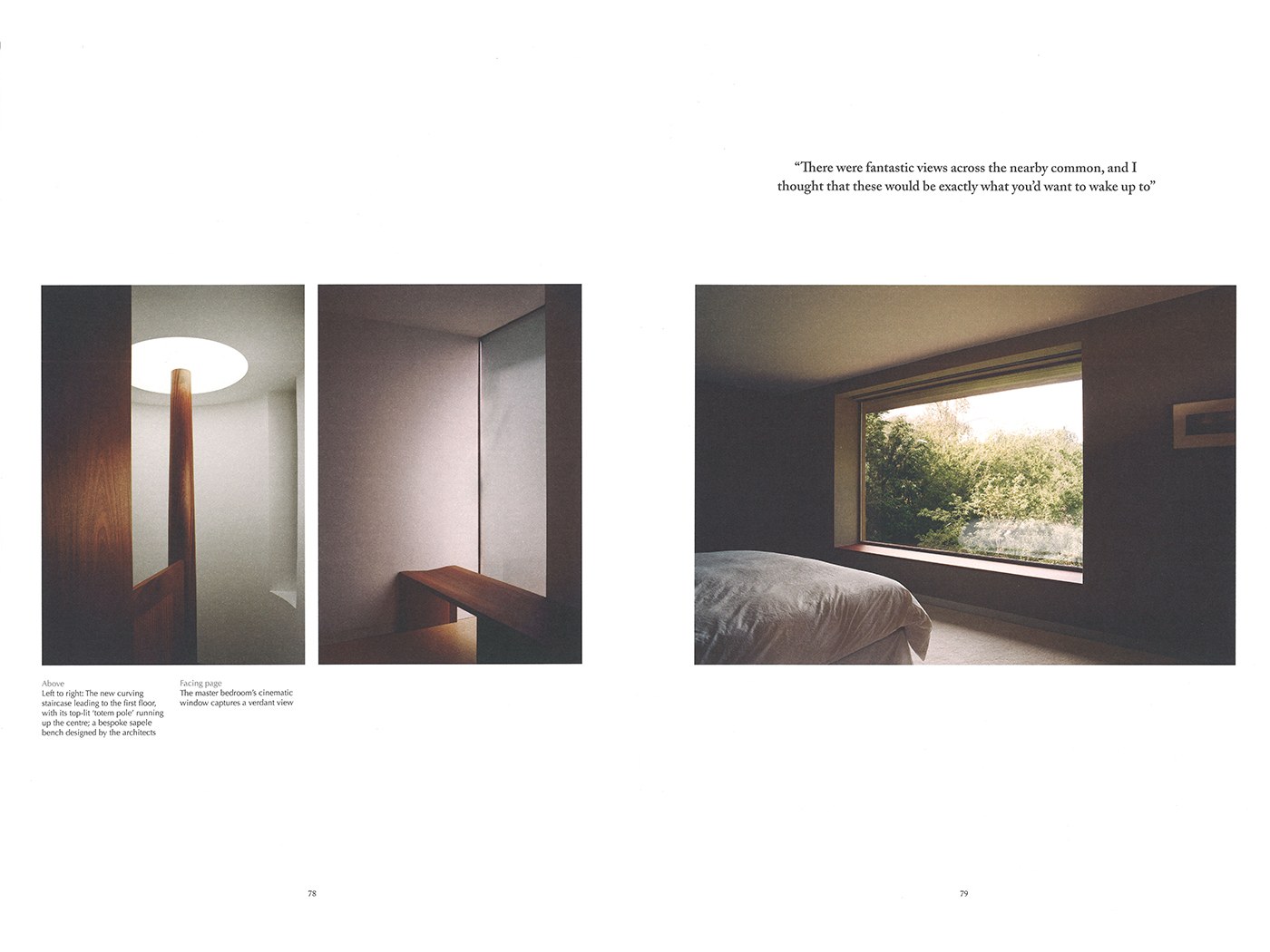

The extension incorporates some expressive design elements. “You can see the new staircase rising in the distance from the front door,” Smalley explains. “There’s a circular skylight above it, which intersects with the five-metre tall ‘totem pole’ that acts as the centre post in the stair. It’s level with the ceiling so it looks like it is holding up the sky. It was quite an abstract move, which the clients really liked.”

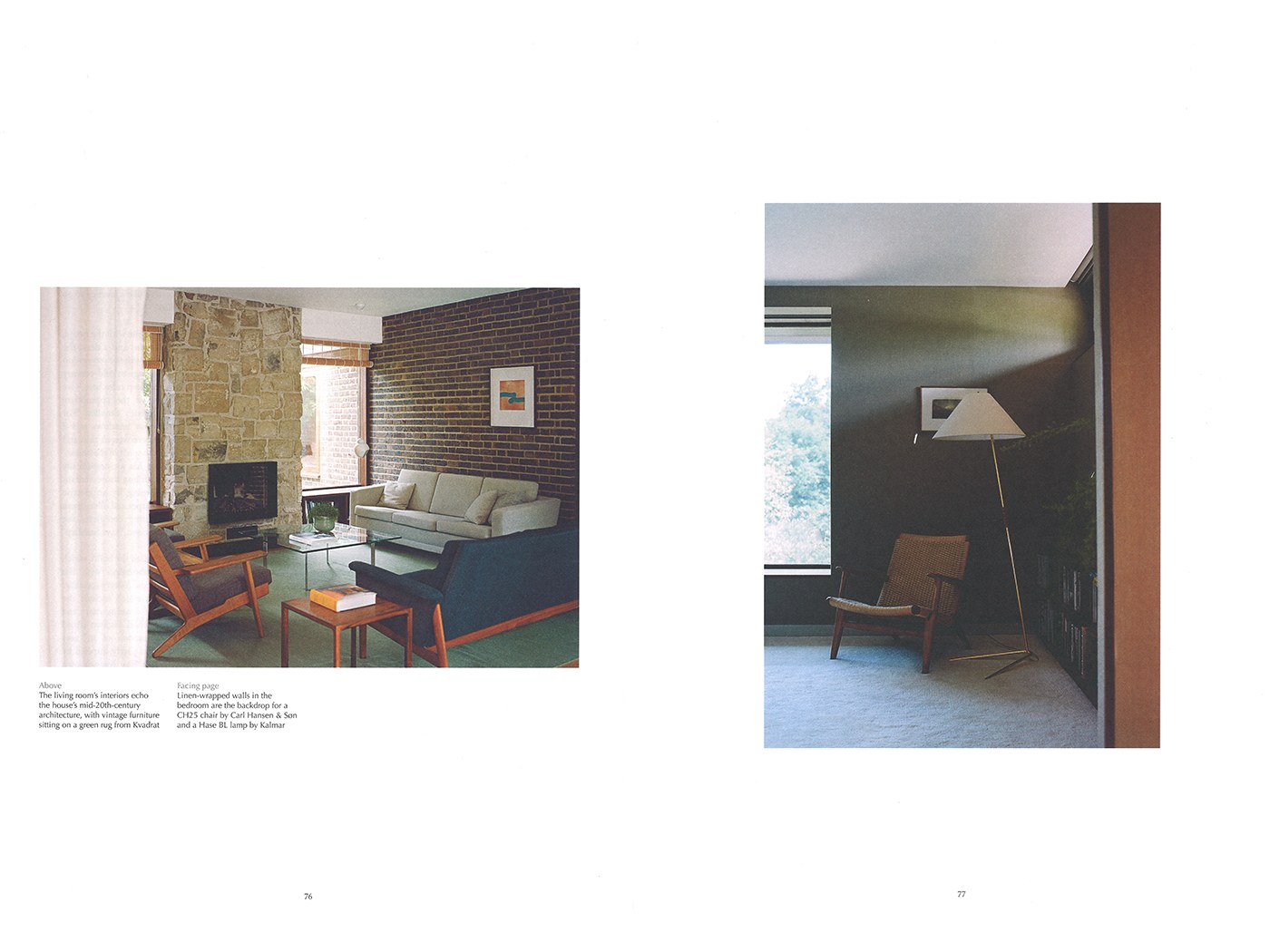

The original main corridor was doubled in width, giving the house a more spacious feel, complete with double pivot doors that fold together in the centre of the room. “We knocked the kitchen and dining room together – they were previously linked only by a serving hatch – and took some space from the courtyard,” says Smalley. Finishes evoke the materials palette of the era, with white walls juxtaposed with rough render and cork tiles underfoot, laid in the original pattern. “We tried to get back to the thinking of the 1950s,” says the architect. “It’s a type of modernism that came via Mies and Breuer, where you get that sense of flowing space. The original owners’ daughter actually wrote us a nice email saying that her parents would have approved.”

The renovation added 85 sqm to the house’s original 185 sqm floorplan and includes a new guest suite carved from the original garage space, with a birch-lined box forming a shower room. Smalley has managed to increase the sense of space in what was already an incredibly open and generous design. “You’re always looking across to foliage, no matter where you stand – it’s just an incredibly nice house to be in,” he says. The generous wide-width corridors feel like extensions of the rooms, while the garden is ever present. “It’s like a journey to go upstairs to bed,” he says.

Although some furniture came with the house, including a sofa, a headboard and a desk, the eclectic material choices ensure the renovation isn’t a straightforward homage to mid-century style. “We could make our own rules here – we decided for ourselves what the appropriate level of change was,” explains Smalley. “For example, choosing the new windows was a complicated process – they’re not thin and metal but they’re in the spirit of the house.” The new master bedroom has a cinematically proportioned window to frame those verdant views, revealed each morning by an electric blind. A white shag-pile carpet and olive-green linen used as a wallcovering completes the look. “It’s like a kind of cocoon,” says Smalley.

AMLY Construction handled the build, which was Smalley’s fifth collaboration with the contractors. A one-man-band joinery specialist made the bespoke items, which include the birch ply doors, cedar-clad dressing room and the monumental sapele wood kitchen island unit. “We made models of it,” says Smalley, noting that it was partly inspired by the Los Angeles architect Ray Kappe’s own house in Pacific Palisades, built in the 1960s. Other bespoke pieces include two wallhangings woven by textile artist Catarina Riccabona, along with bespoke Douglas fir wall lights. “The clients are slowly filling the house with furniture, but they’re taking their time,” Smalley says. “They’re content to wait and avoid it becoming a mid-century museum. They wanted everything to be done solidly and well – this is a house that’s built to last,” he adds. “It’s a very good attitude to have.”

text: Jonathan Bell photography: Harry Crowder