i 15

Reading in the Palais Royal

Stung by this week’s cruel acts in the name of a god, but warmed by the very human resilience Paris has shown in response, my thoughts turned to a time when I used to visit the city regularly in search of peace, to sit and read and draw.

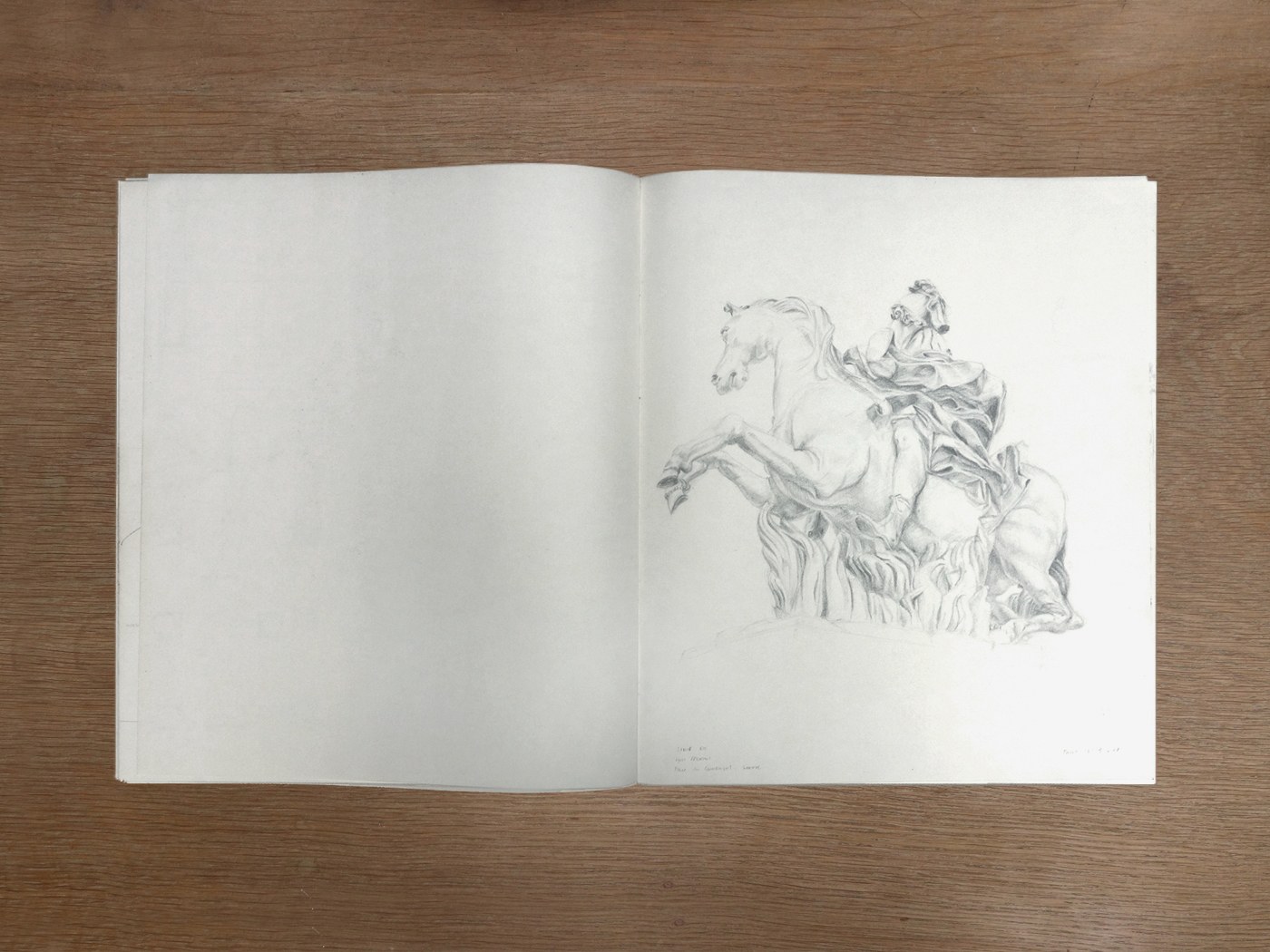

A city which always seemed to be two crucial degrees warmer than London, helped by the natural warmth of its stone, Paris feels the epitome of late European civilisation. Its history is written in its buildings and streets – the medieval islands, tight-grained left bank and broader right, scored through by Haussmann’s high-handed boulevards (which continued to be built up to 1927) and overwritten by the presidential grands projets of the later 20th century. These grand gestures can feel overwhelming manifestations of power (and at Versailles plain scary) – Regent Street was the only equivalent boulevard London’s gentler parliamentary system could manage (is it just that our royal family was more interested in horses? or simply that they were German and couldn’t convey their wishes to an English court?), and our grands projets are more prosaic railway stations. In recent years Paris perhaps fell into a stasis, but this is to be countered by plans from its new mayor.

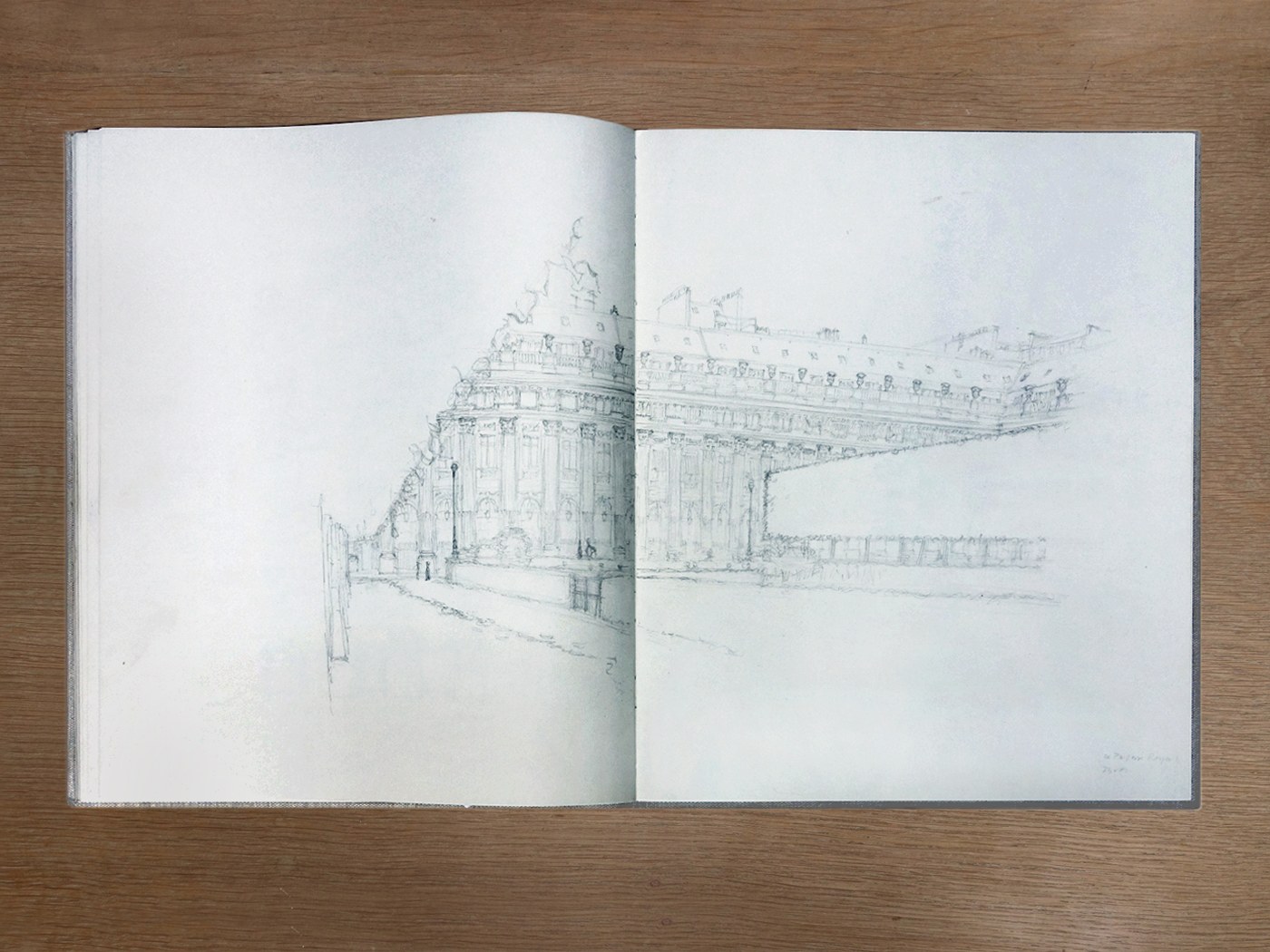

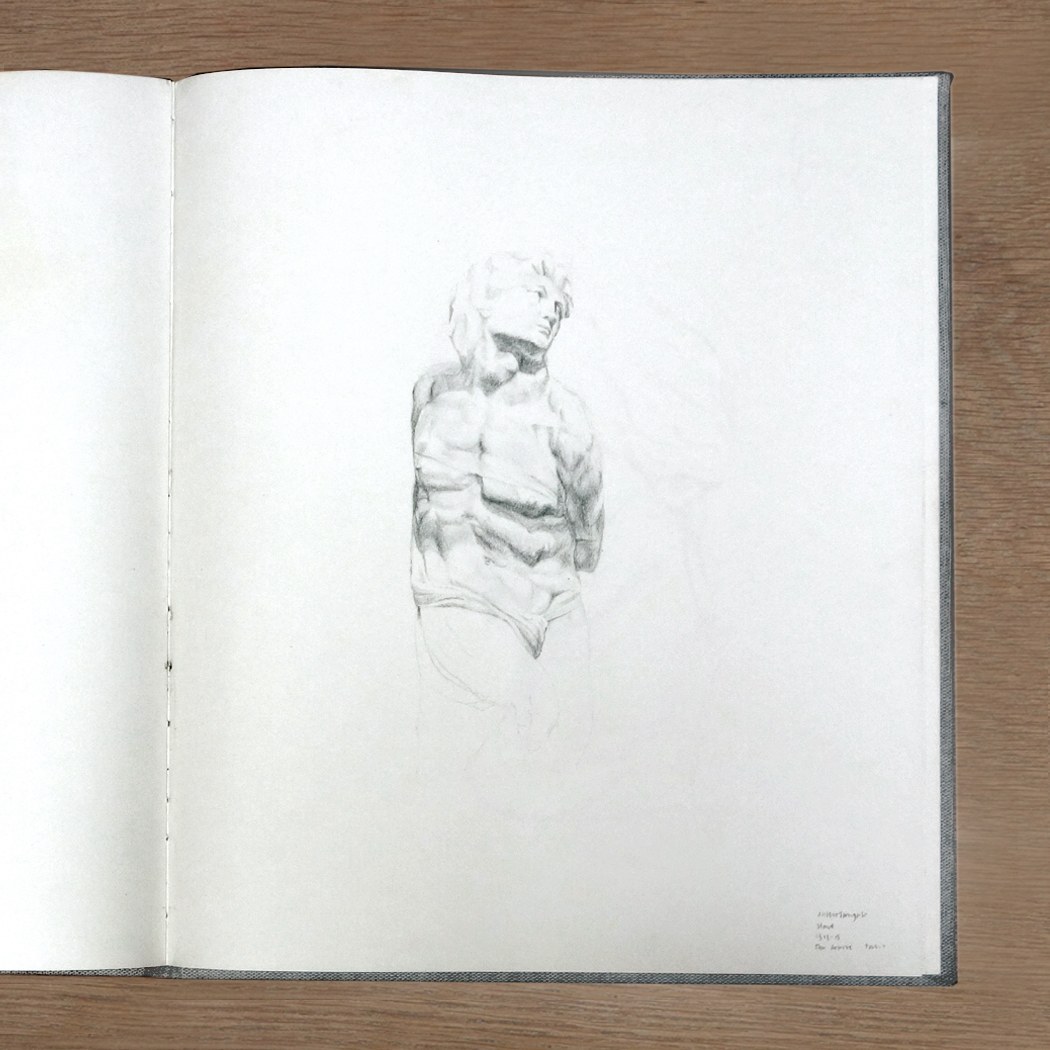

My first trips were spent discovering every last building and place, from Le Nôtre to Le Corbusier, but, tiring of traipsing up endless boulevards, each subsequent trip narrowed down my circle of experience until, contrary to my natural inclination to the tighter irregularity of the left bank, all I wanted to do was to go and sit in the Palais Royal and read in the sun, between bouts of sketching at the Louvre just across the Rue de Rivoli and a croque monsieur over the river (my favoured café remained in the left bank).

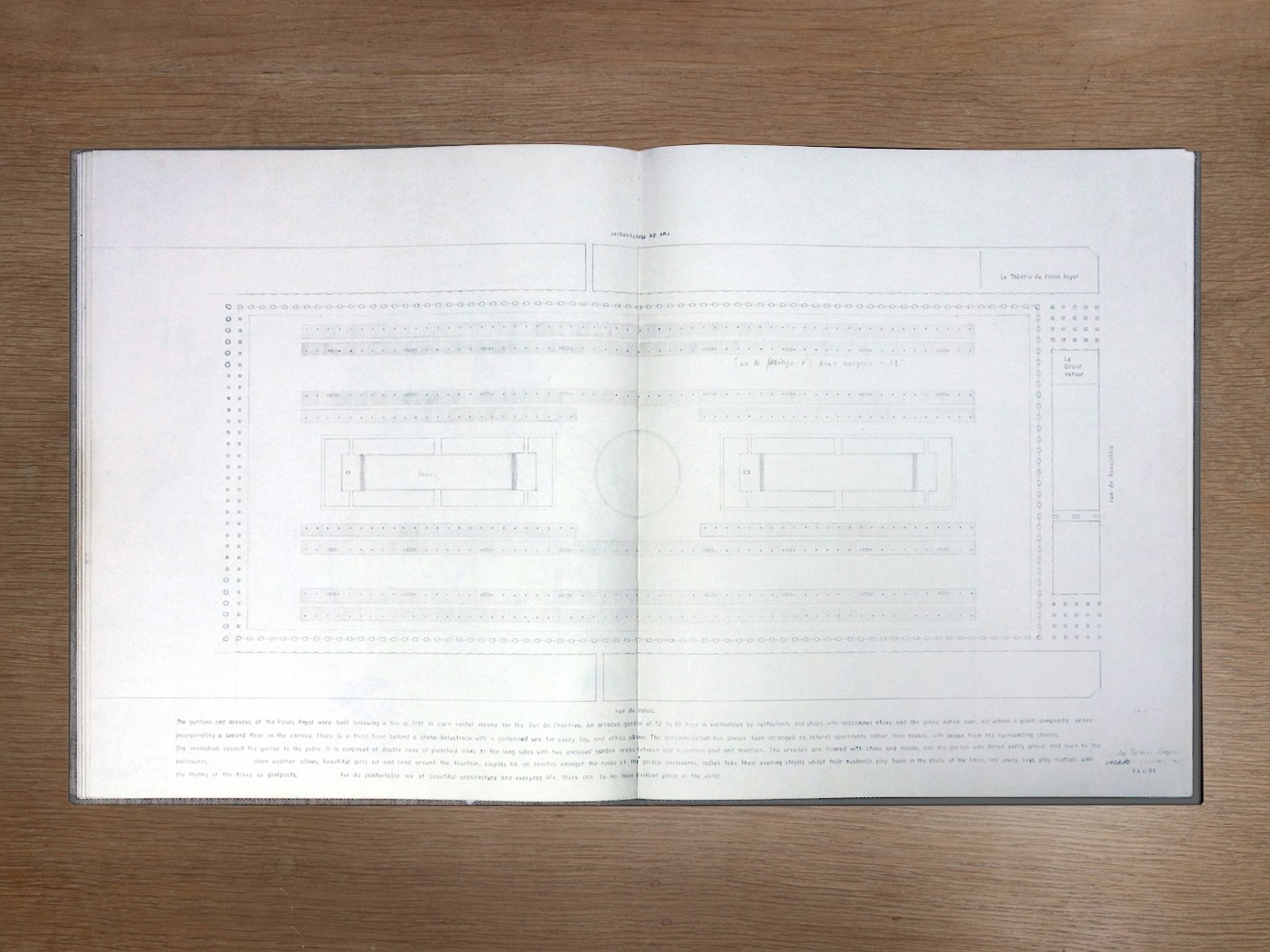

The Palais Royal is a place of deep civility, Paris’s equivalent of the local town square with its boules pitch; a place to marvel at the quiet achievement of man’s society. Large enough for you to lose an end from your sphere of vision (it is comparable in size to St Mark’s Square in Venice) and yet still very definitely contained, I wrote the following in my sketchbook under a laborious measured survey of the whole square:

The gardens and arcades of the Palais Royal were built following a fire in 1781 to earn rental income for the Duc de Chartres. An arcaded garden of 72 by 30 bays is surrounded by restaurants and shops with mezzanines above and the piano nobile over, all within a giant composite order incorporating a second floor in the cornice. There is a third floor behind a stone balustrade with a garlanded urn for every bay, and attics above. The accommodation has always been arranged as lateral apartments rather than houses, with access from the surrounding streets.

The revolution opened the garden to the public. It is composed of double rows of pleached limes to the long sides with two enclosed garden areas between and a central pool and fountain. The arcades are floored with stone and mosaic, and the garden with dense sandy gravel and lawn to the enclosures. When weather allows, beautiful girls sit and read around the fountain, couples lie on benches amongst the roses of the garden enclosures, ladies take their evening strolls whilst their husbands play boules in the shade of the limes, and young boys play football with the trunks of the trees as goalposts. For its comfortable mix of beautiful architecture and everyday life, there can be no more civilised place in the world.

I hope today it is providing a place for solace, as places can, safe in the uncertainty of human existence.