i 19

Est Living

An interview for Est Living

Firstly, could you please tell us a bit about your path to becoming an architect and starting your own firm?

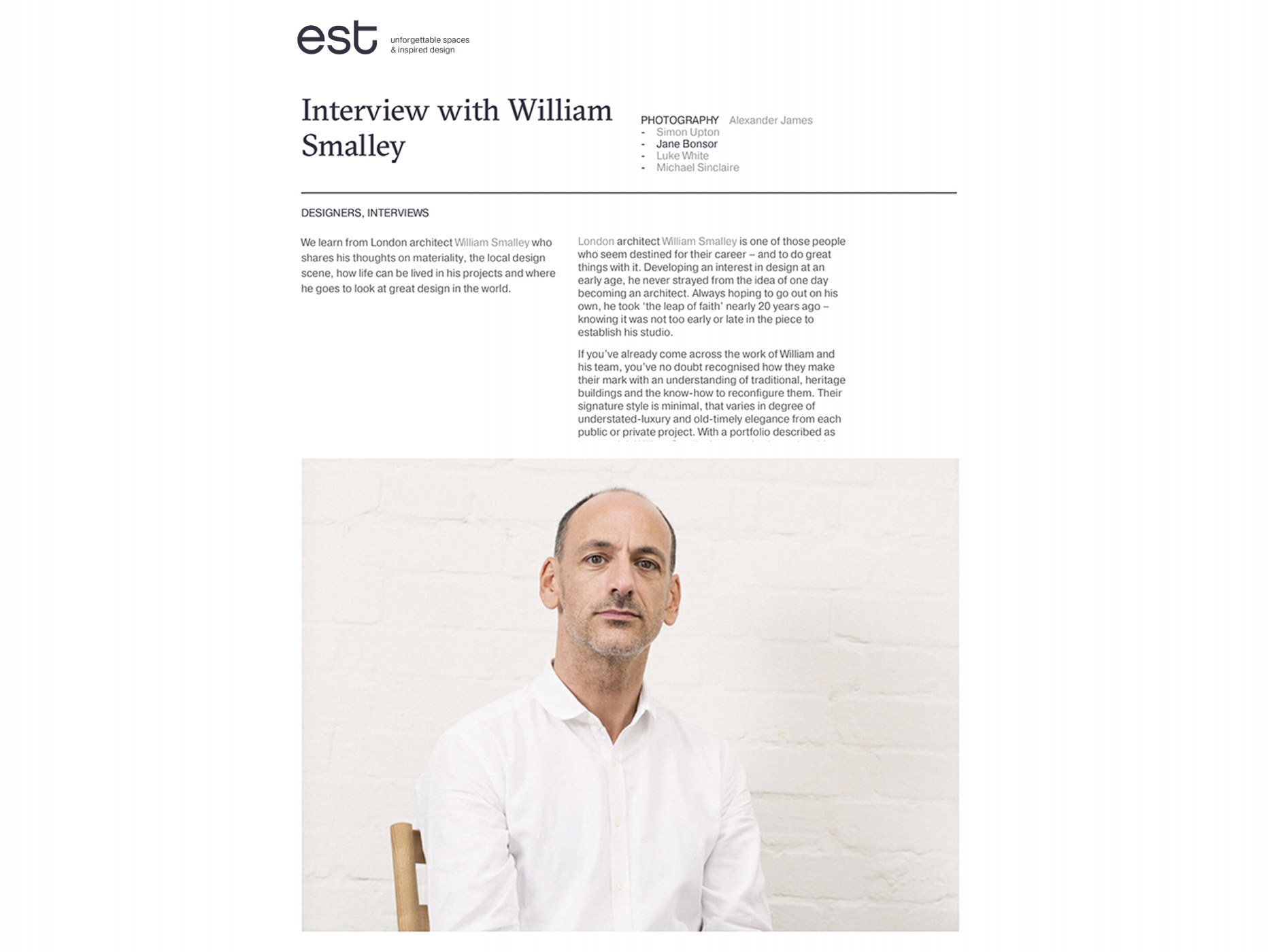

I knew I wanted to be an architect at the age of about eight. I spent all my time designing buildings, and my village school headmaster bought me a copy of the Architectural Review when I was 10 which sealed it.

I studied in Edinburgh and then worked for myself for a few years, but to qualify you have to work for an office, which I did for about eight years. I think you know when the time is right to set up your own studio – not too early and not too late. It’s a bit of a leap of faith, but that it’s what I had always wanted to do must have helped.

How would you describe your approach to residential design?

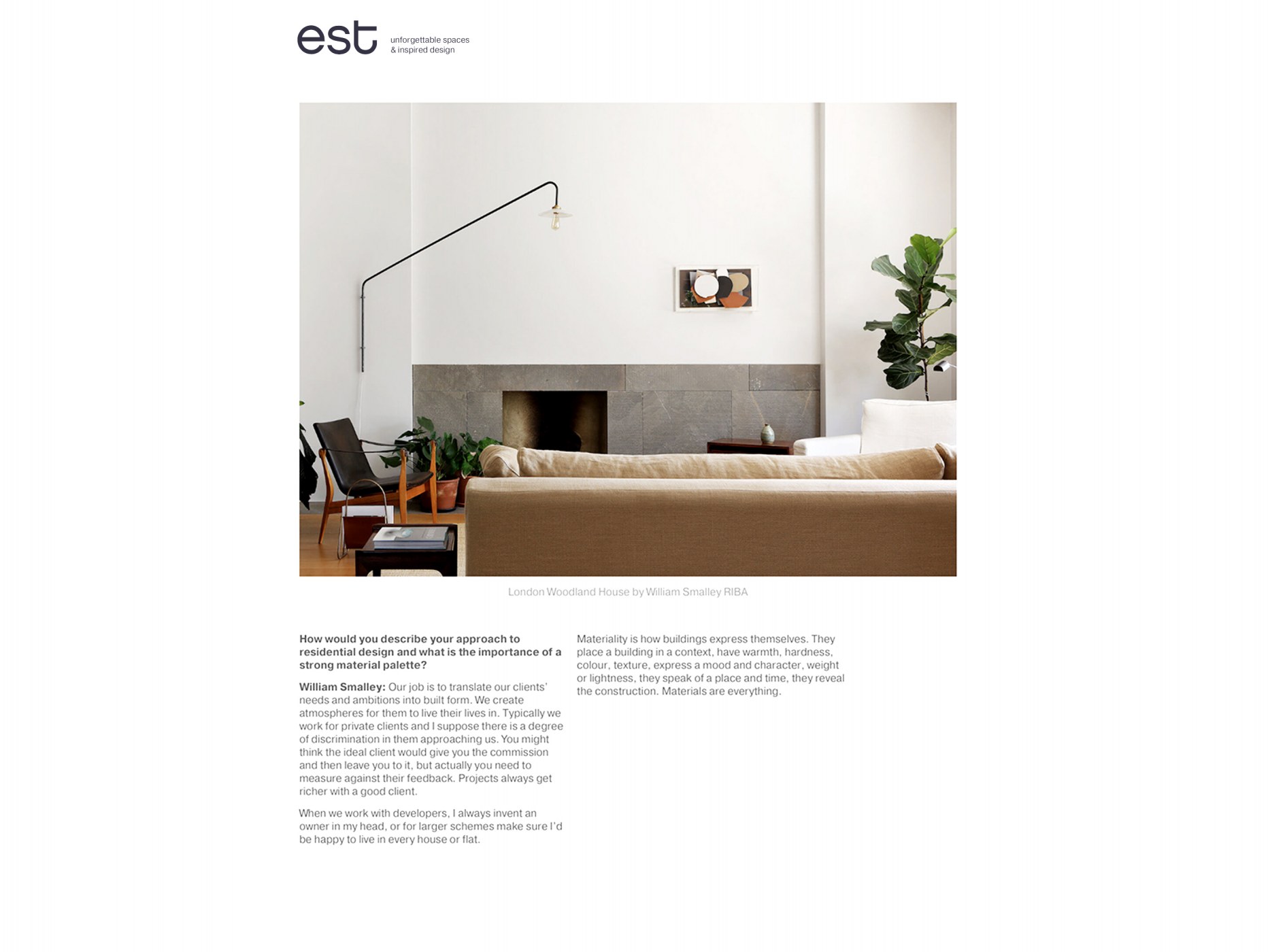

Our job is to translate our clients’ needs and ambitions into built form. We create atmospheres for them to live their lives in.

Typically we work for private clients, and I suppose there is a degree of discrimination in their approaching us. You might think the ideal client would give you the commission and then leave you to it, but actually you need to measure against their feedback. Projects always get richer with a good client.

When we work with developers, I always invent an owner in my head, or for larger schemes make sure I’d be happy to live in every house or flat.

What is the importance of a strong material palette?

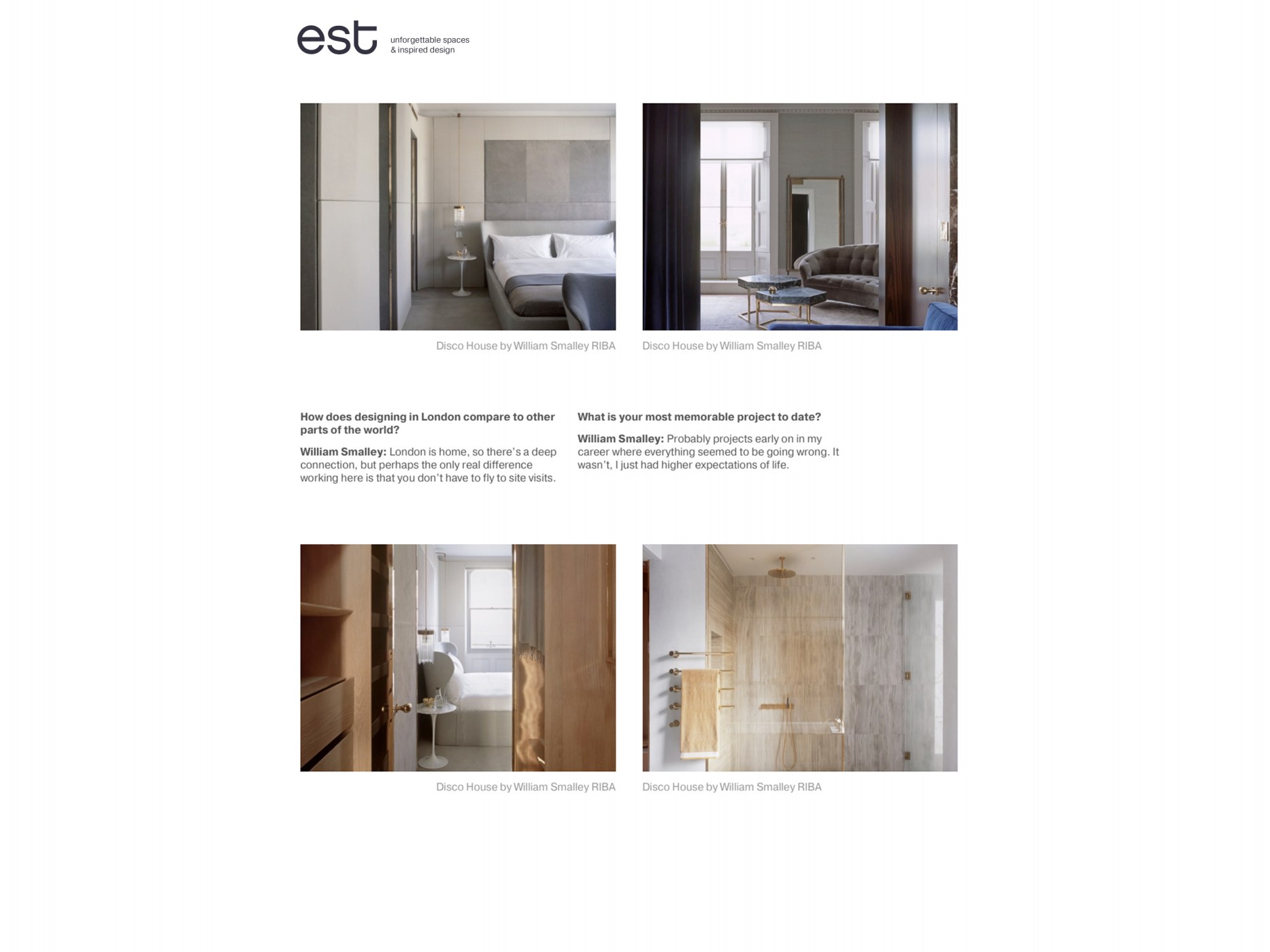

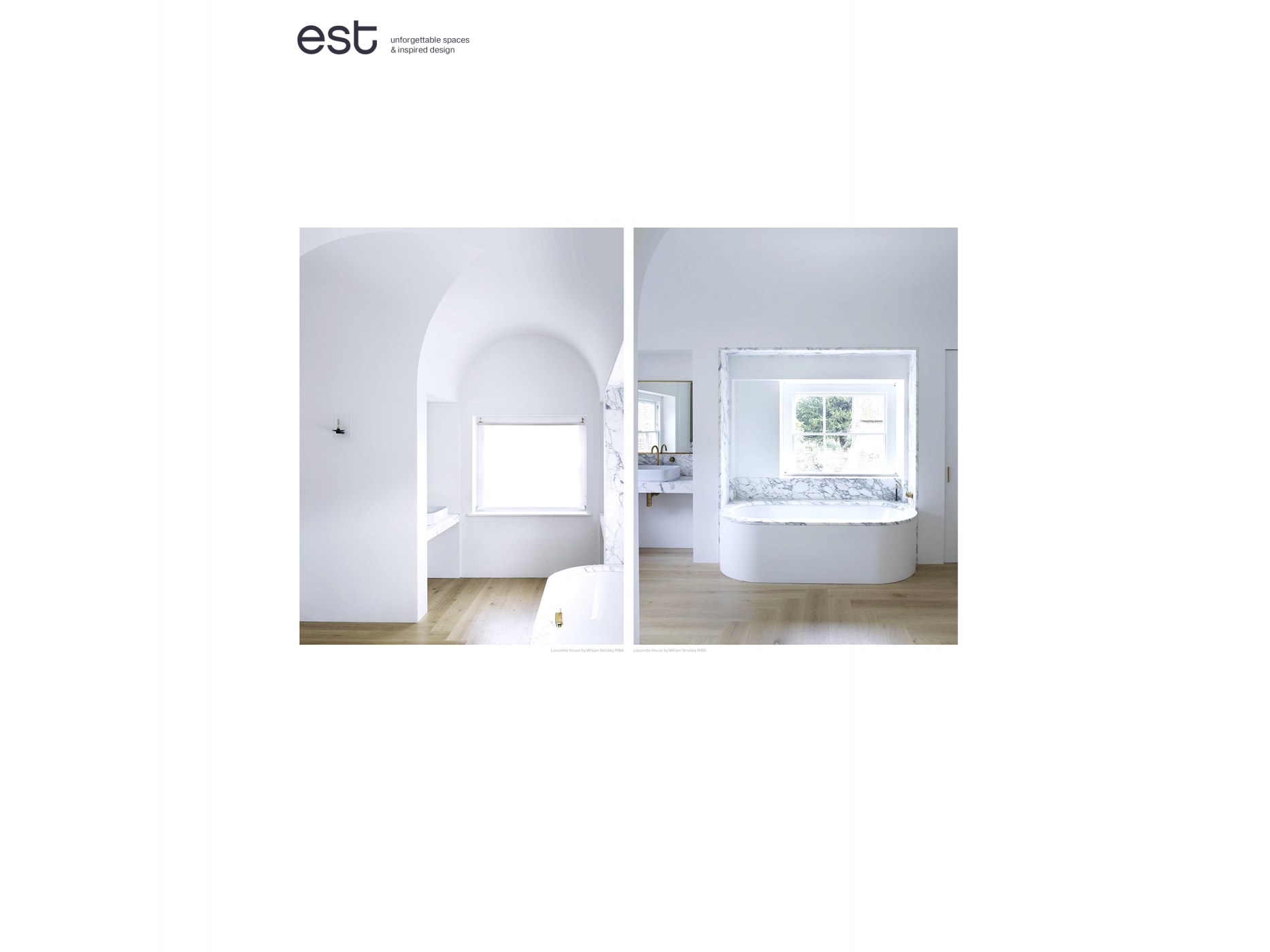

Materiality is how buildings express themselves. They place a building in a context, have warmth, hardness, colour, texture, express a mood and character, weight or lightness, they speak of a place and time, they reveal the construction.

Materials are everything.

Your design office is based in London but you’ve worked on projects in New York and the French Alps. Could you please tell us a bit about these projects and how they came about?

Building in London can be constraining, and from our tiny studio in Bloomsbury I have always intended to work further afield – if nothing else it’s nice to get out for site visits.

It is impossible to design a building if you haven’t visited the site. There might seem an inherent contradiction in seeking to make buildings which are rooted to their place, as we do, when you are designing in a place you don’t know, but the answer is to be as open to intuition as possible. If you are then a response comes quickly, and appropriately. If a response doesn’t come you are probably in the wrong job.

Our projects abroad have come about through clients at home. The New York project is for the sister of a London client. It is the complete re-ordering of a large Upper West Side apartment on Manhattan. The apartment had a Scandinavian feel, so perhaps a European architect was more appropriate than it might seem.

In France, we have been working on a chateau in the Alps for some London clients, where we took the cathedral-like roof off, rotten after 350 years, and replaced it with a new timber structure to make a 2,500sq ft, three-storey-high party room lined in French larch.

How does designing in London compare to other parts of the world?

London is home, so there’s a deep connection, but perhaps the only real difference working here is that you don’t have to fly to site visits.

What is your most memorable project to date?

Probably projects early on in my career where everything seemed to be going wrong. It wasn’t, I just had higher expectations of life.

What do you hope to achieve in your career that you haven’t yet?

I feel I have only just started. Architecture is a long game.

What are your:

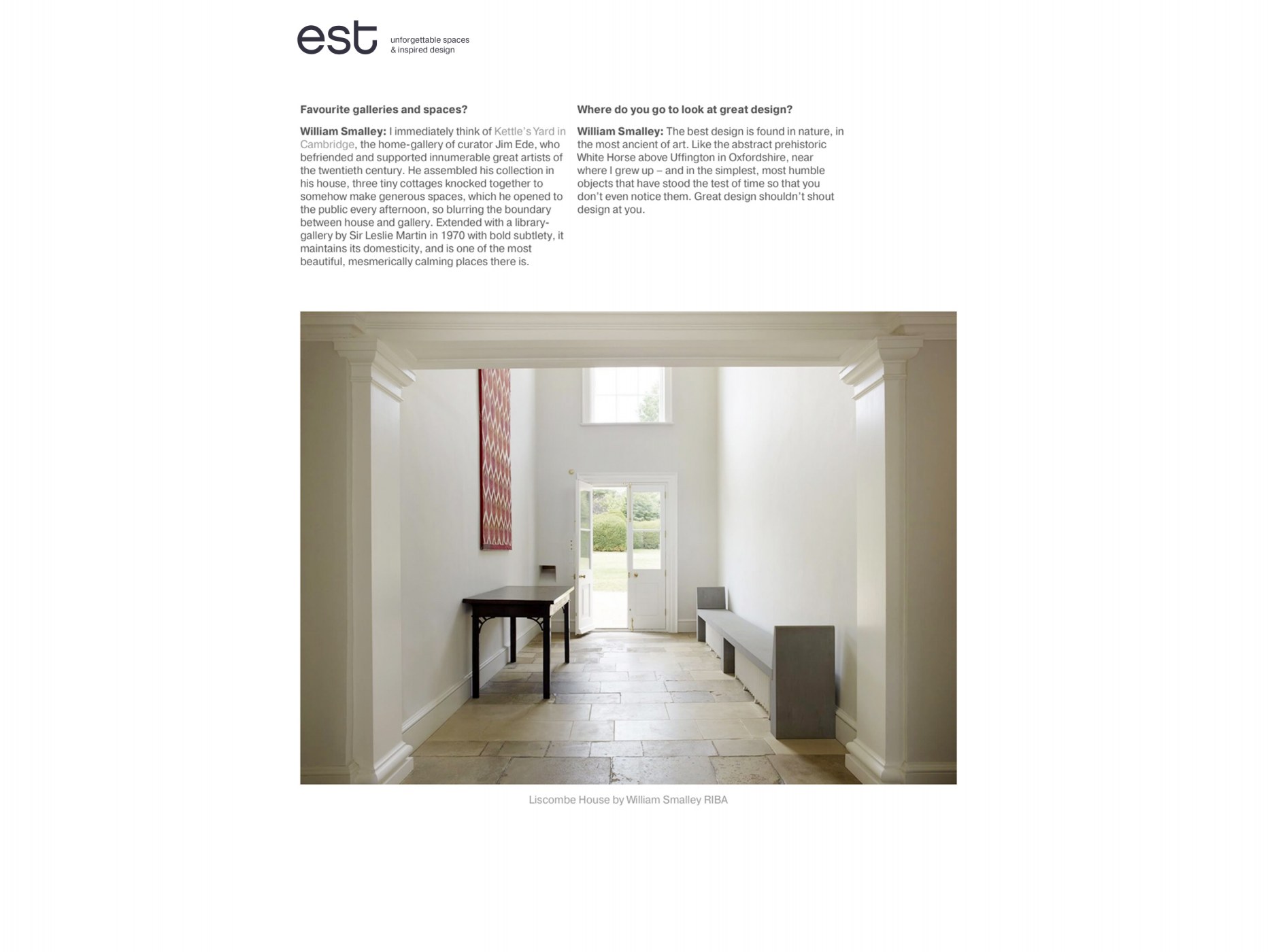

Favourite galleries and spaces?

I immediately think of Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, the home-gallery of curator Jim Ede, who befriended and supported innumerable great artists of the twentieth century. He assembled his collection in his house, three tiny cottages knocked together to somehow make generous spaces, which he opened to the public every afternoon, so blurring the boundary between house and gallery. Extended with a library-gallery by Sir Leslie Martin in 1972 with bold subtlety, it maintains its domesticity, and is one of the most beautiful, mesmerically calming places there is.

Favourite local designers or studios?

I don’t hang out with architects as much as I probably should. We are across an alley from 6A Architects, and my old-time hero John Pawson is up the road in Kings Cross. There are good architects all over London, at least until Brexit.

Favourite design stores?

Sigmar on the Kings Road in London sell perfect examples of elegant mid-century furniture and objects, and are the UK agent for the fifth-generation Viennese workshop of Carl Auböck and their century-long history of designing beautiful brass, leather and bone household objects – ashtrays that make you want to take up smoking and bottle corks that make you not want to finish the bottle.

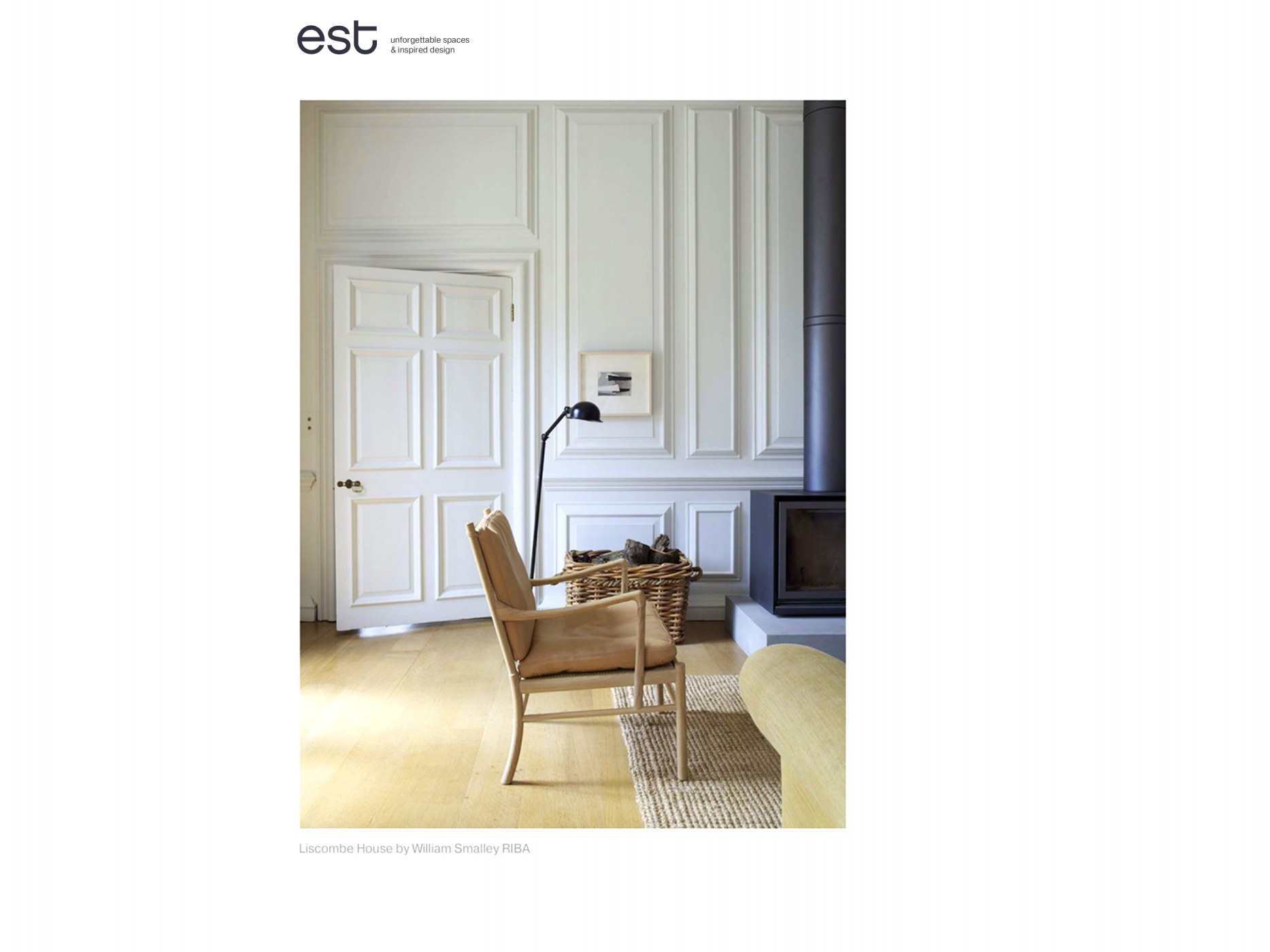

Where do you go to look at great design?

The best design is found in nature, in the most ancient of art – like the abstract White Horse from 2,500BC above Uffington in Oxfordshire, near where I grew up – and in the simplest, most humble objects that have stood the test of time so that you don’t even notice them.

Great design shouldn’t shout Design at you.