xii 20

Russell Maliphant

Apropos of nothing, at the year end I was reminded of watching over the summer an online video of Push, a dance by choreographer Russell Maliphant.

I am aware that there is a fine line between a dancer pratting around meaninglessly on stage and abstract expressionistic perfection – and that writing about it also threatens to sit on the wrong side of that line, although one way or the other I’ve crossed it already by writing before about Maliphant’s dance Broken Fall.

That was the first work of his I saw, almost by chance (friends thought I might like it), at the Royal Opera House when it was premiered in 2003 by the incredible Sylvie Guillem and the Ballet Boyz, Michael Nunn and William Trevitt. I went back the next two nights in a row to see it again, and again. Sitting in whichever seat was available last-minute was a chance to work out my preferred viewpoint for his work, which is first balcony: slightly raised, to see the work as a whole, at one remove, as viewer rather than with any pretence of participation.

Maliphant sets the bar so high that he is more or less the only choreographer I follow; the only one for me who consistently sits on the right side of the line.

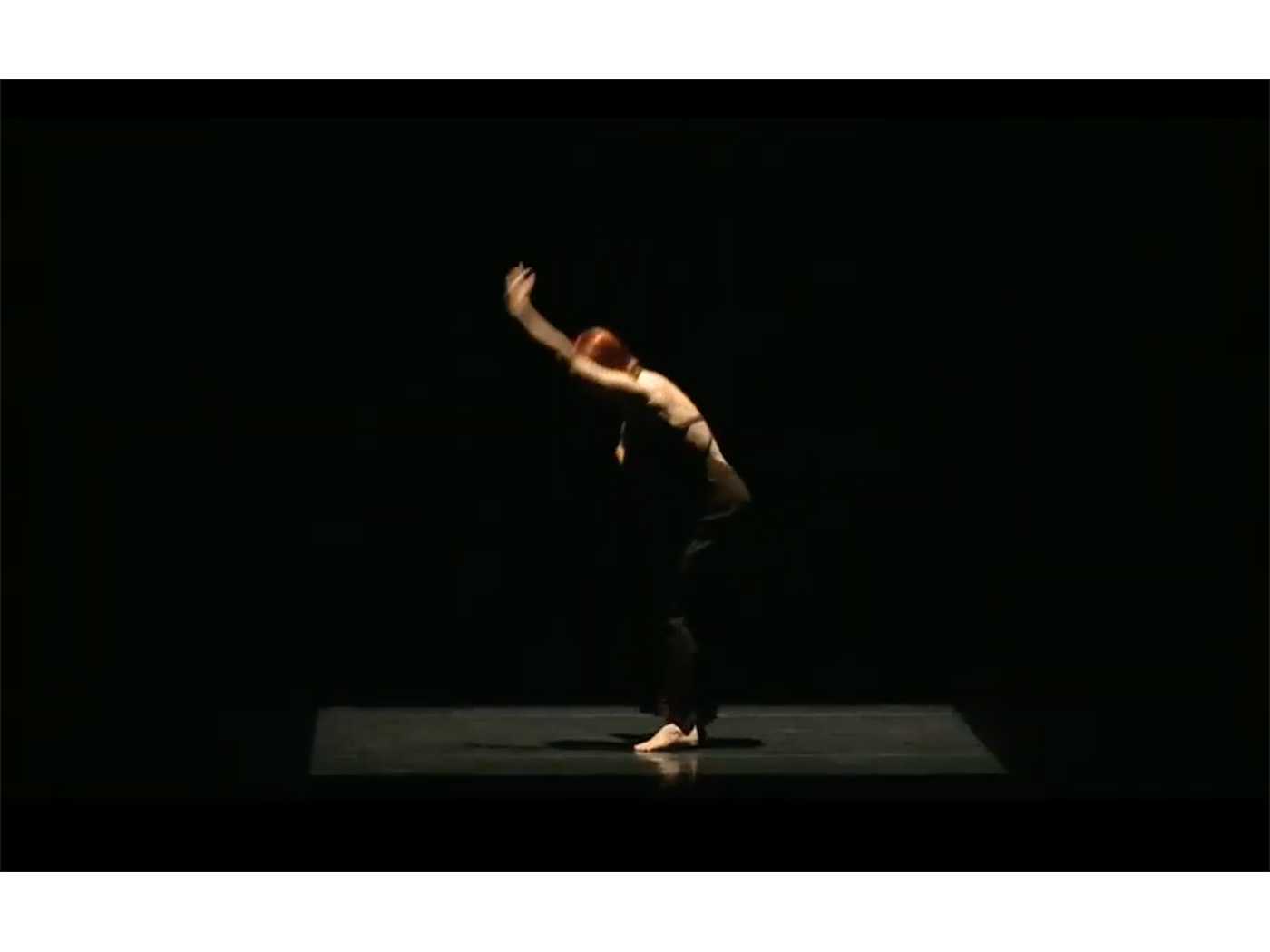

His work has an abstract quality, immersing you into introverted, inhabited worlds formed solely of movement, light, and music. They reveal themselves slowly. Typically they are solos, duets or trios. Mostly they seem to be intimate portraits of relationships; tender, touching and distant.

The sense of immersion comes from the lighting and sound, as integral to the work as Maliphant’s choreographic expression.

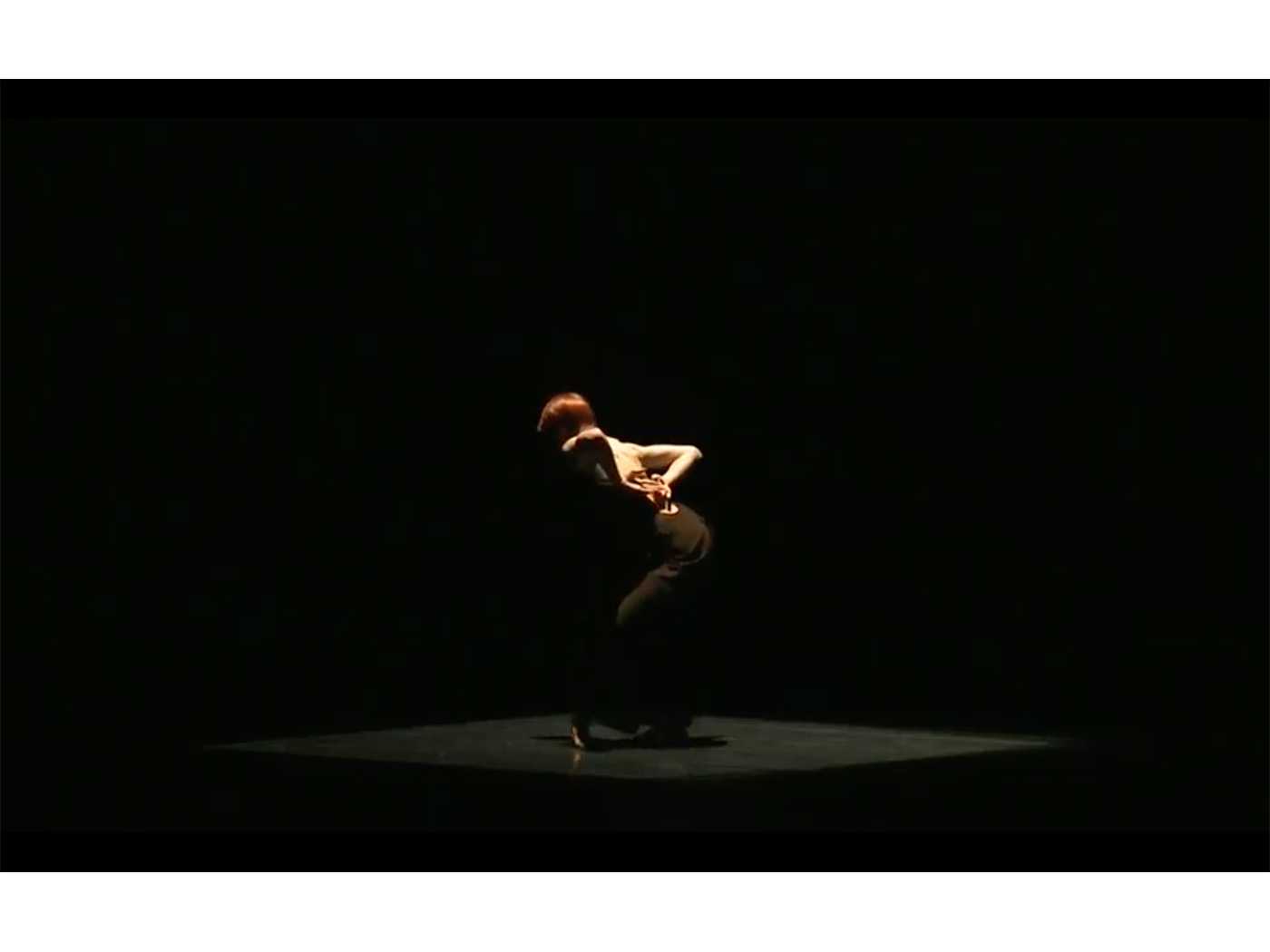

Under collaborator Michael Hulls’ lighting, shadow is as important as light. They are not afraid to use shadow; there is almost always more darkness on stage than light. The stage’s extents are rarely revealed, and the dancers, and the centre of gravity of the pieces, repeatedly appear out of and retreat into shadow. Focussed shafts of light mean that at times only some of the dancer’s body is lit, giving a heightened charge (though interestingly, the strobe effect of a whirring arm in a beam of light is provided not by pulsing lights as I had imagined, but in the human eye watching). An early and mesmerising piece, Shift, from 1996, danced by Maliphant himself, has him slowly moving around the stage through crossed beams of light so that he is silhouetted in strips of light on the back of the stage, dancing with his shadows. In another, Two, from 1997, Sylvie Guillem uncoils her incredible limbs standing otherwise still in a shaft of light.

Music plays, from quiet to the far side of loud, always somehow feeling the most physical, tangible, part of the dance. It often morphs through a piece, from one piano key, repeated, or a single haunting bowed string, to full-on house; from chamber concert to nightclub, as shadowed and nuanced as the lighting.

Movements are always gentle, even when fast. There is always fluidity, poise. There is an innate modernity, without shouting it – as in of course it’s modern, why would something new be anything else rather than Hey! We’re Being Modern! Not following classical form of beginning, middle and end, endings can arrive by surprise, and yet always achieve closure. And though they are perfectly composed, the best of his dances always leave me wanting to watch them again; not immediately, but the next day, to experience the immersion again.

The most remarkable aspect of that immersion, more even than the effortless backward flips (though related), is the sense of transcendence of time: in the immediate sense the dance absorbs you so that you forget time; but also, while watching, time becomes fluid, moving backwards as well as forwards, slowing – stopping even – and speeding; the choreography often involves backward movement, folds unfolding, unwinding reversals, so that time seems to be rewound. And in a bigger sense the dances seem to move freely between eras so that they feel ancient and modem at the same time. This is perhaps what gives a sense of mystery to Maliphant’s work, grounded and then unexpectedly not.

The titles tend to be simple, one or two words: Push, Shift, Critical Mass; which at once point to simplicity and belie complexity, suggesting abstract notions, and avoiding the pressure I feel around poetry of not getting the reference. I haven’t read anything about the meaning behind his work or specific dances; I hope it isn’t intended to be explicit. References are there, but implicit. The work does not seek to be poetic, but achieves poetry. There is something in it that can’t be explained. Maybe this inexplicableness is the mark of a true creative act; the trace of genius.

Like a great work of art Maliphant’s work teaches you about the world and about yourself. And so in my case about architecture.

His is, and I assume will remain, a small oeuvre. There is perhaps a similarity in the way that my work strikes its own direction, and that clients tend to come to us knowing they want to work with us.

Words and feelings that come to mind to describe Maliphant’s work are: generosity, kindness, care, yearning, coupling, subtlety, grace, tenderness, weight, lightness. His work requires exactitude made effortless. I realise these are all qualities I’d like my architecture to achieve, or that it seeks to achieve, consciously or not. Mostly not.

I come to realise that I’m not much interested in an architecture which attempts to portray movement, other than of light on it, but rather is one which is a vessel for emotions. If this is the lesson of 2020 then the year hasn’t all been in vain.

I have no idea how choreography is recorded. How do you write all that is included in the particular way a hand is held? Similarly, how do you record architecture, your reaction to a space? We did a pitch for a project recently and apart from a medieval castle my references for the site were not of buildings but were artworks – the perfect composition of Edmund de Waal’s recent show Tacet at the New Art Centre, Barbara Hepworth maquettes in her St Ives studio, the scratched surfaces of a Ben Nicholson painting on board, the immersive qualities of an Ivon Hitchens colourfield that seemed to speak of the experience of being on the site, and of what might be. I don’t quite know if they got it, but we got the project.

In a similar vein, I’d like to show new clients a Maliphant dance. An abstract, esoteric test. I think it would be a good check for prospective clients: does Push appeal to you?

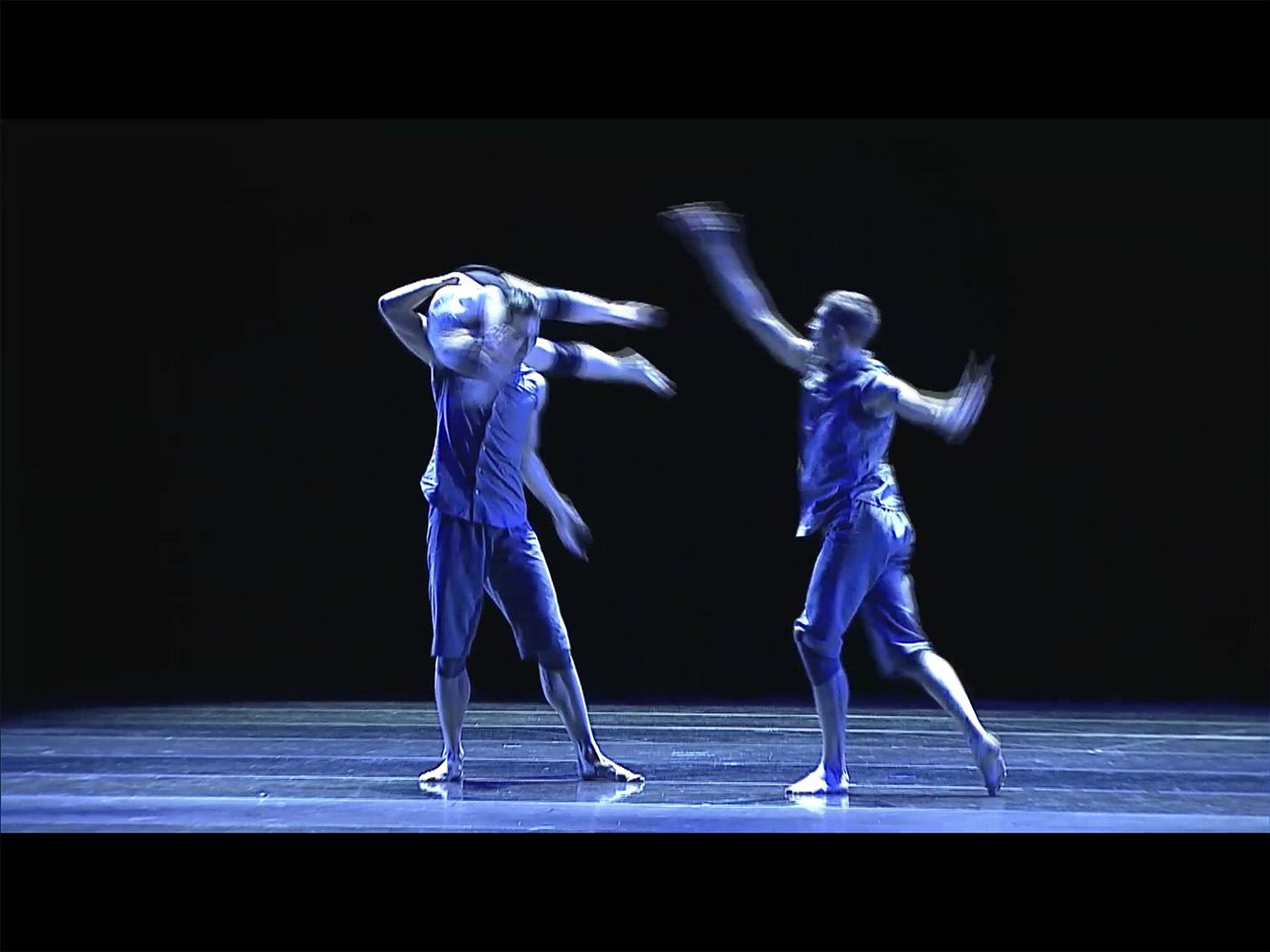

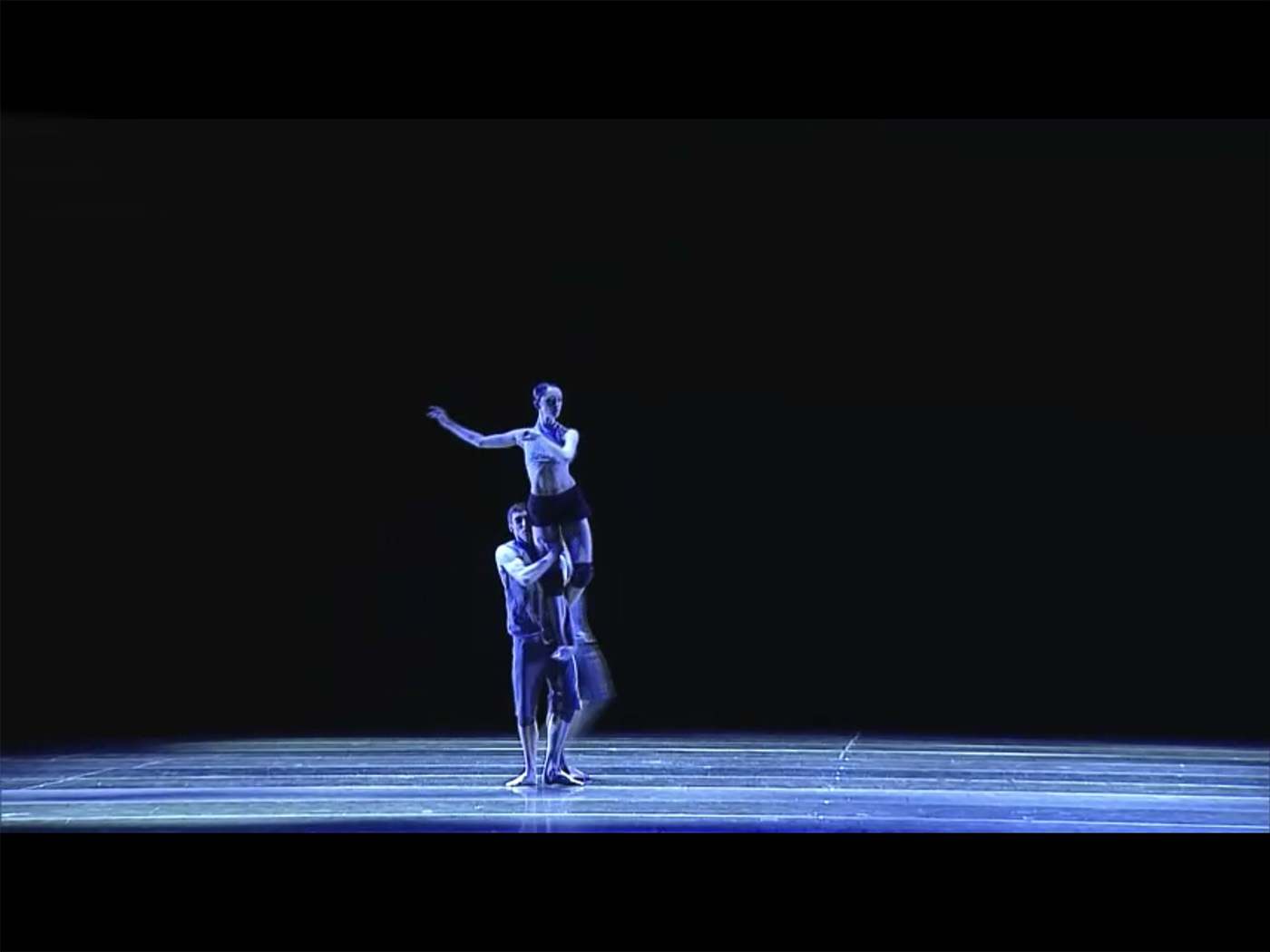

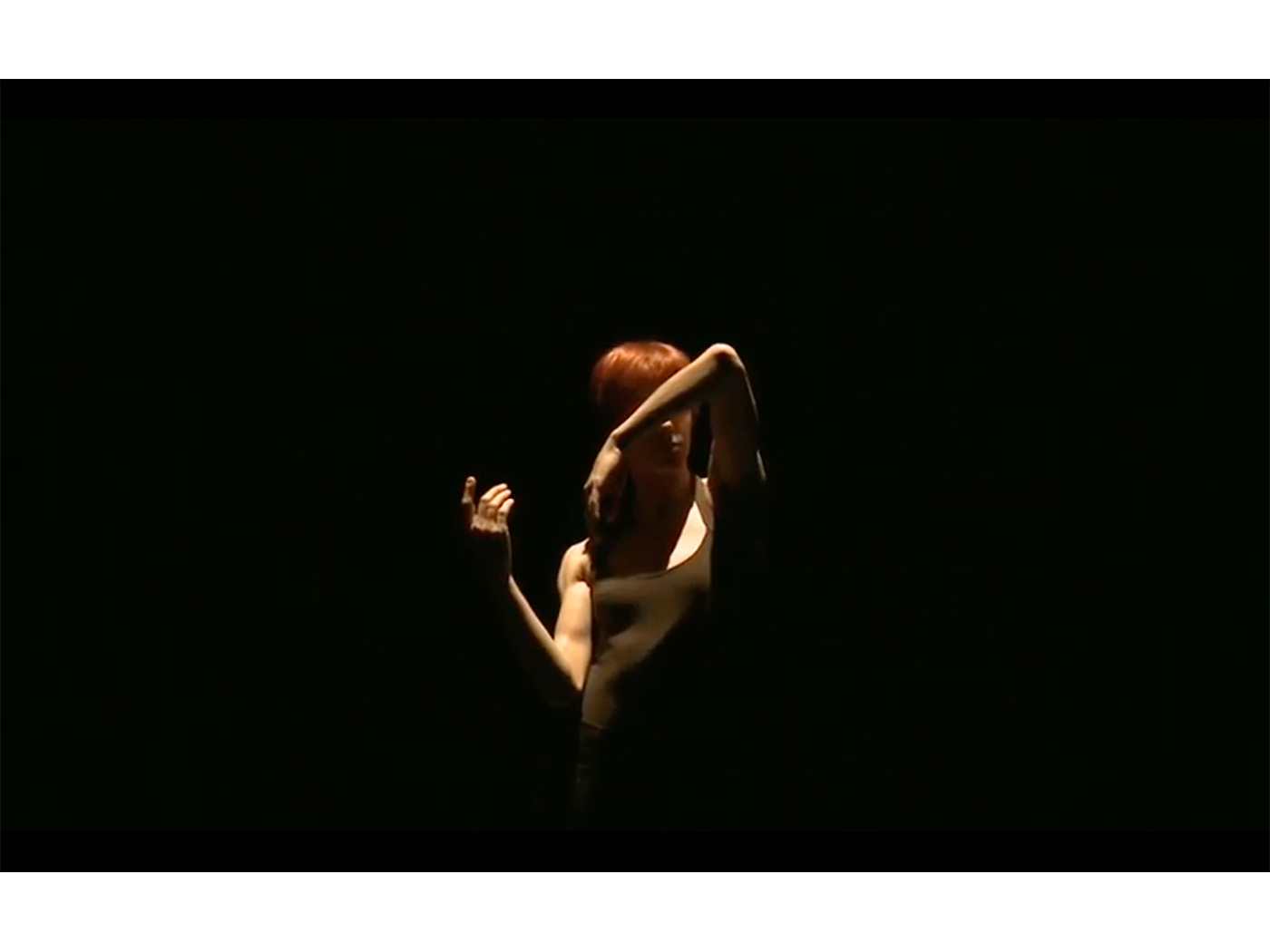

screenshots:

Push danced by Sylvie Guillem and Russell Maliphant, 2006

Broken Fall danced by Jeanette Karaeka, Jinhao Zhang and Jonah Cook, Bavarische Staatsoper, 2020

Two danced by Sylvie Guillem, 2011