Luis Barragán

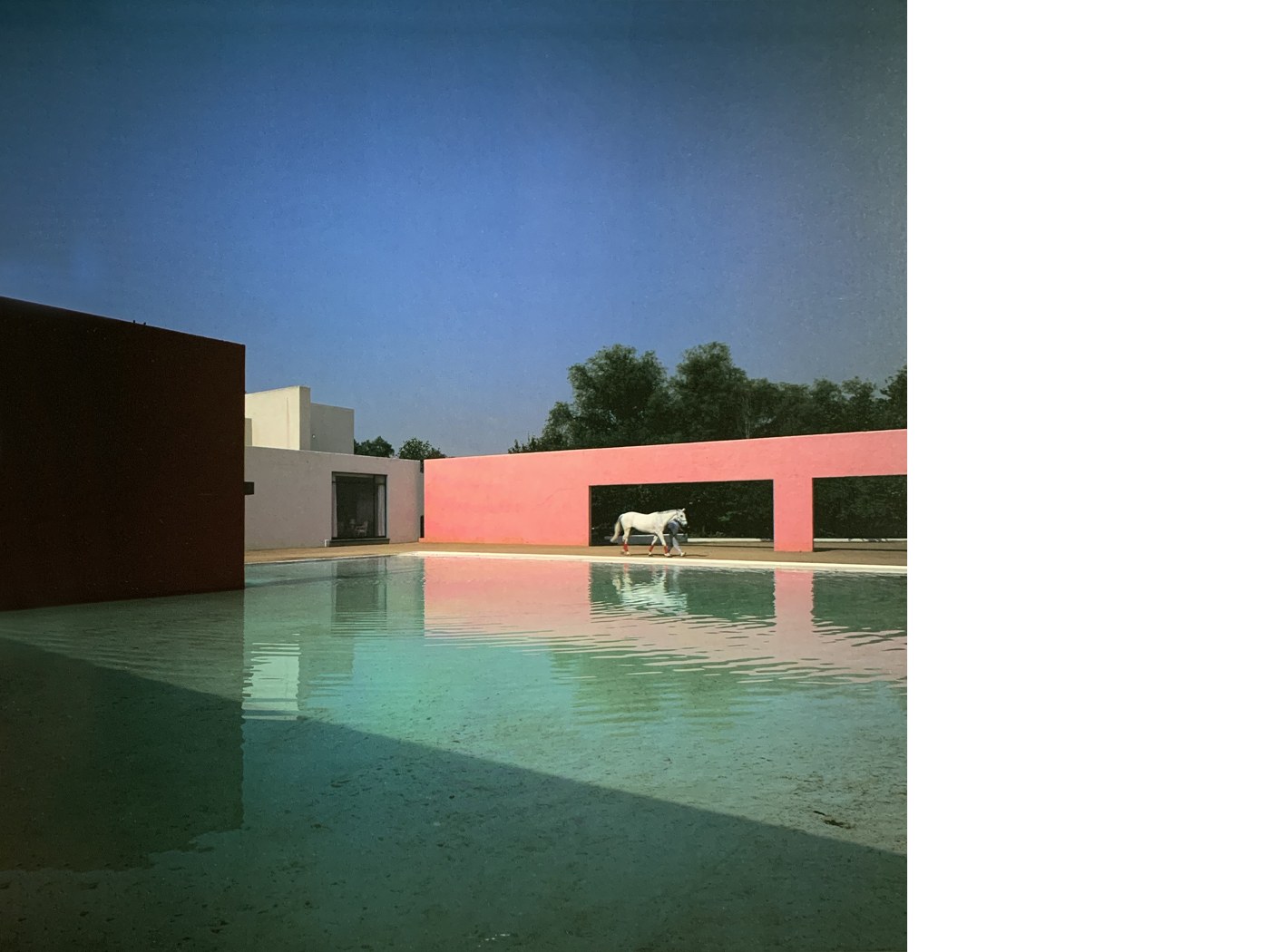

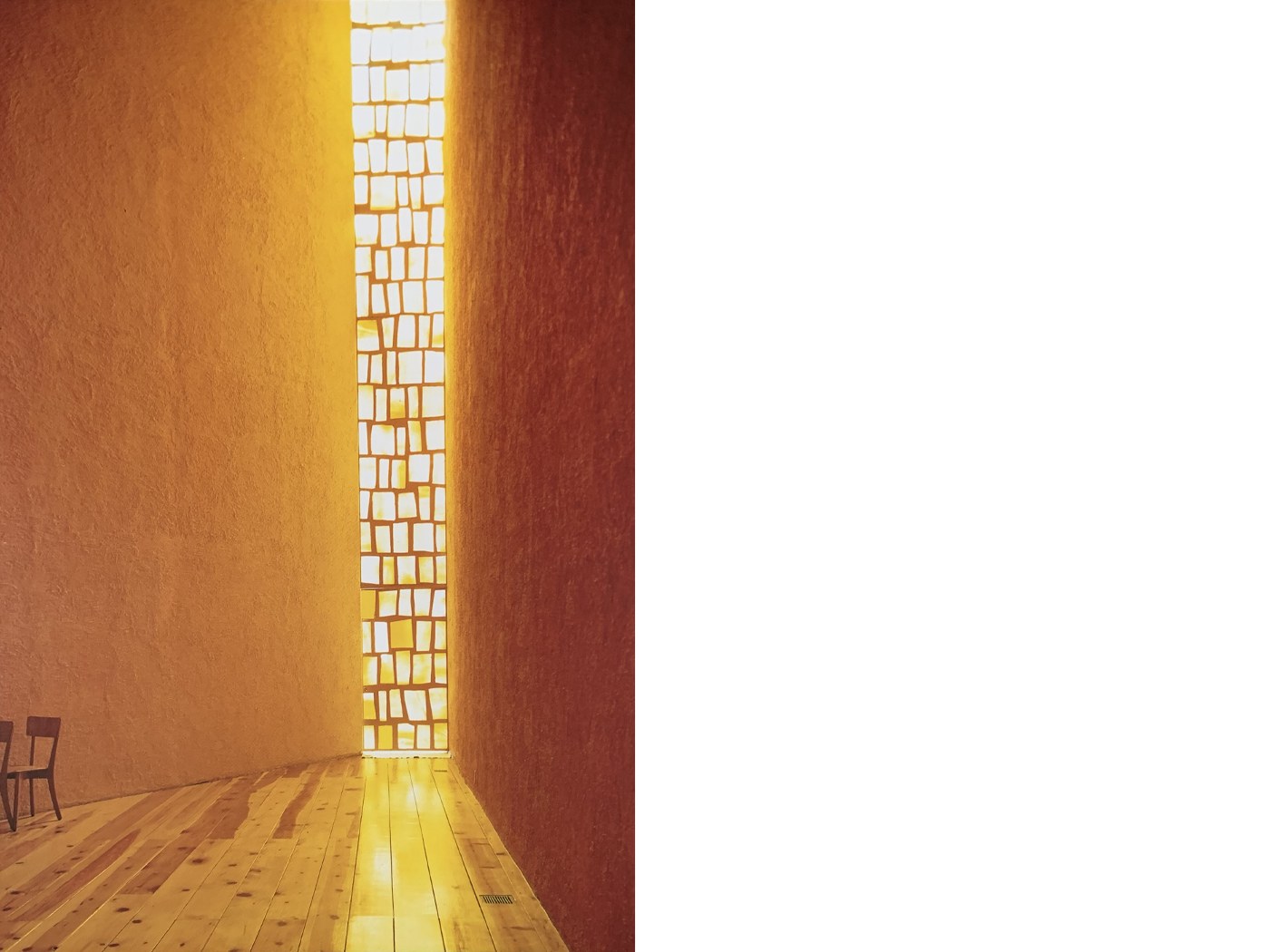

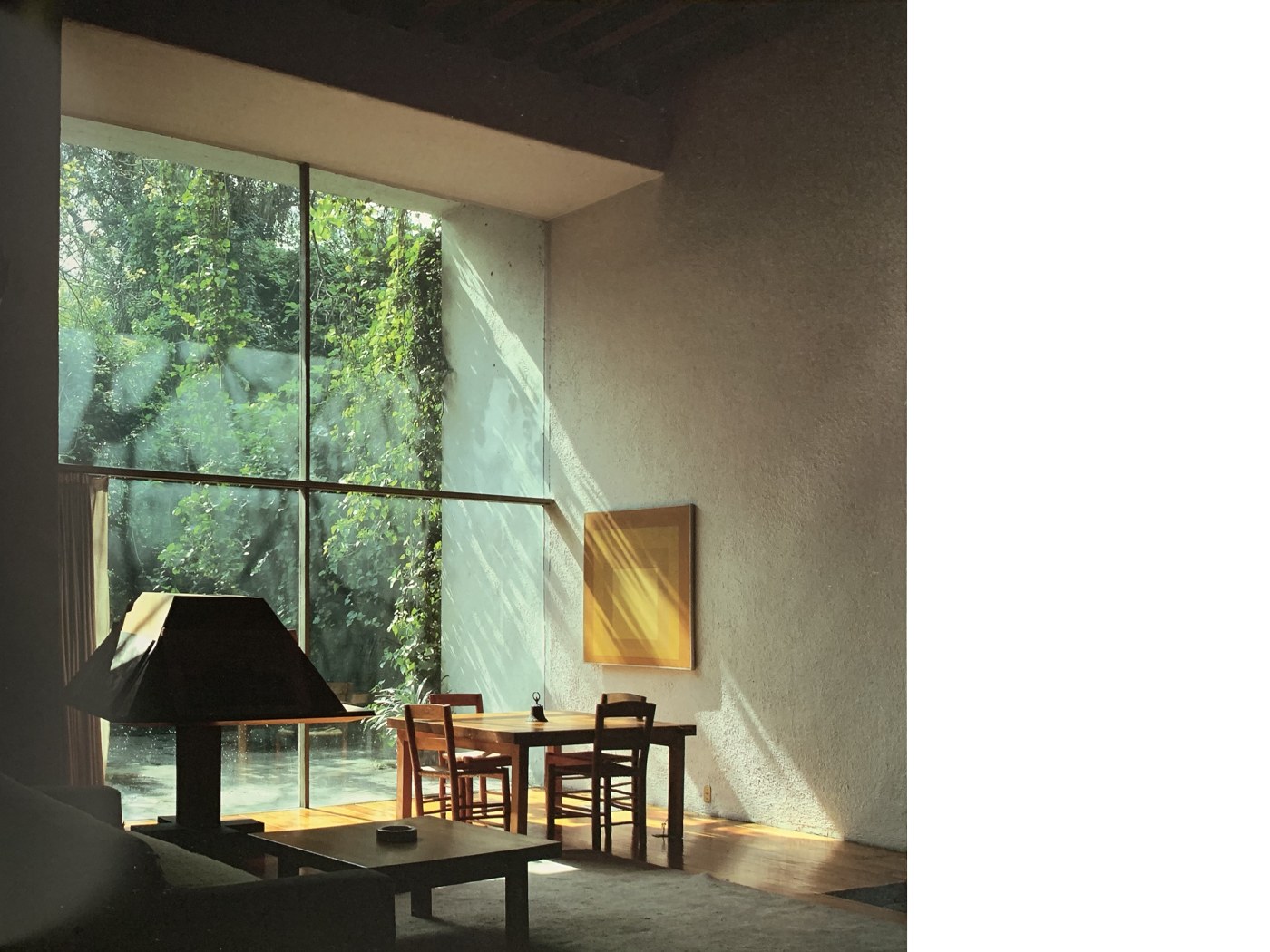

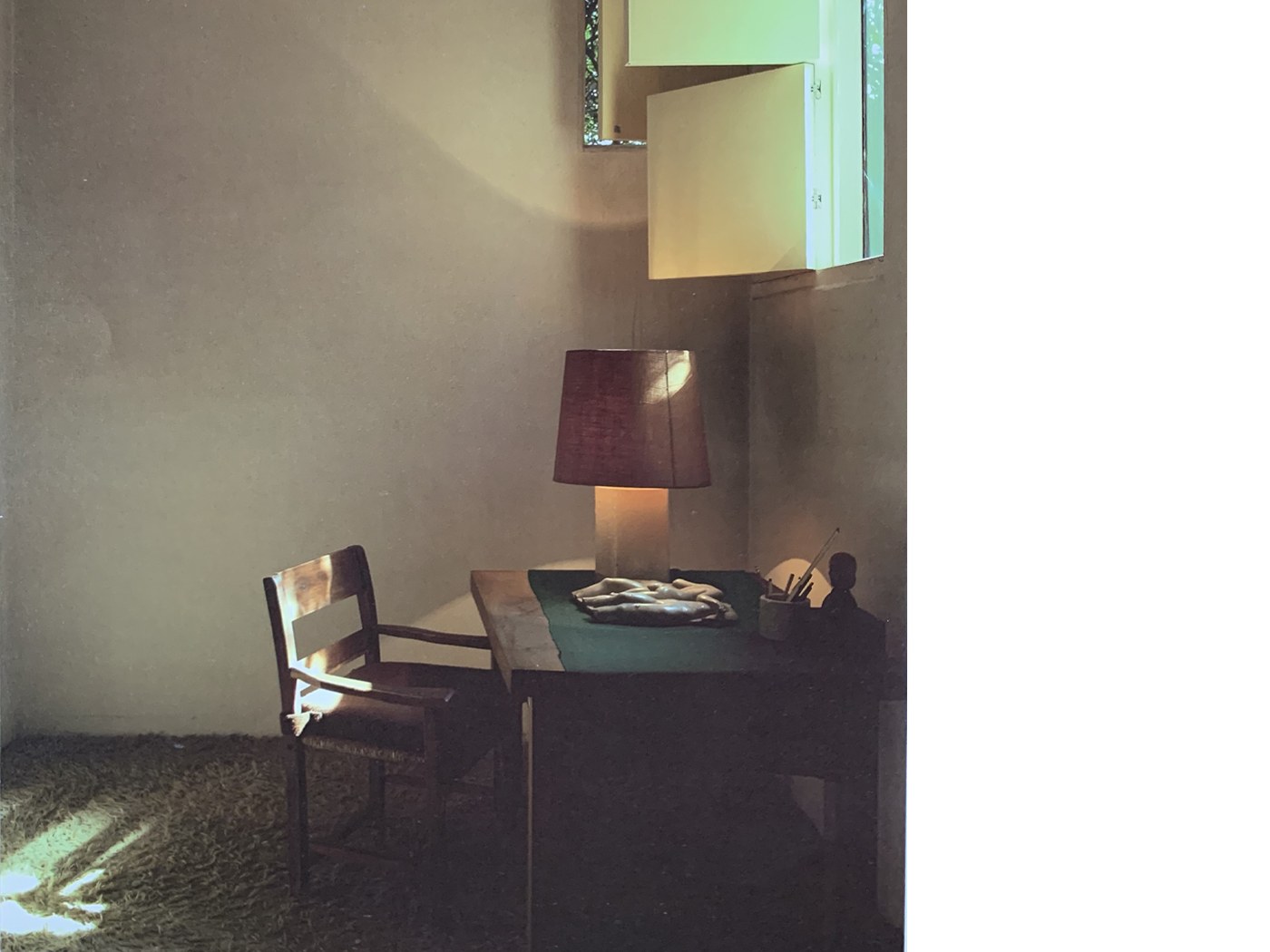

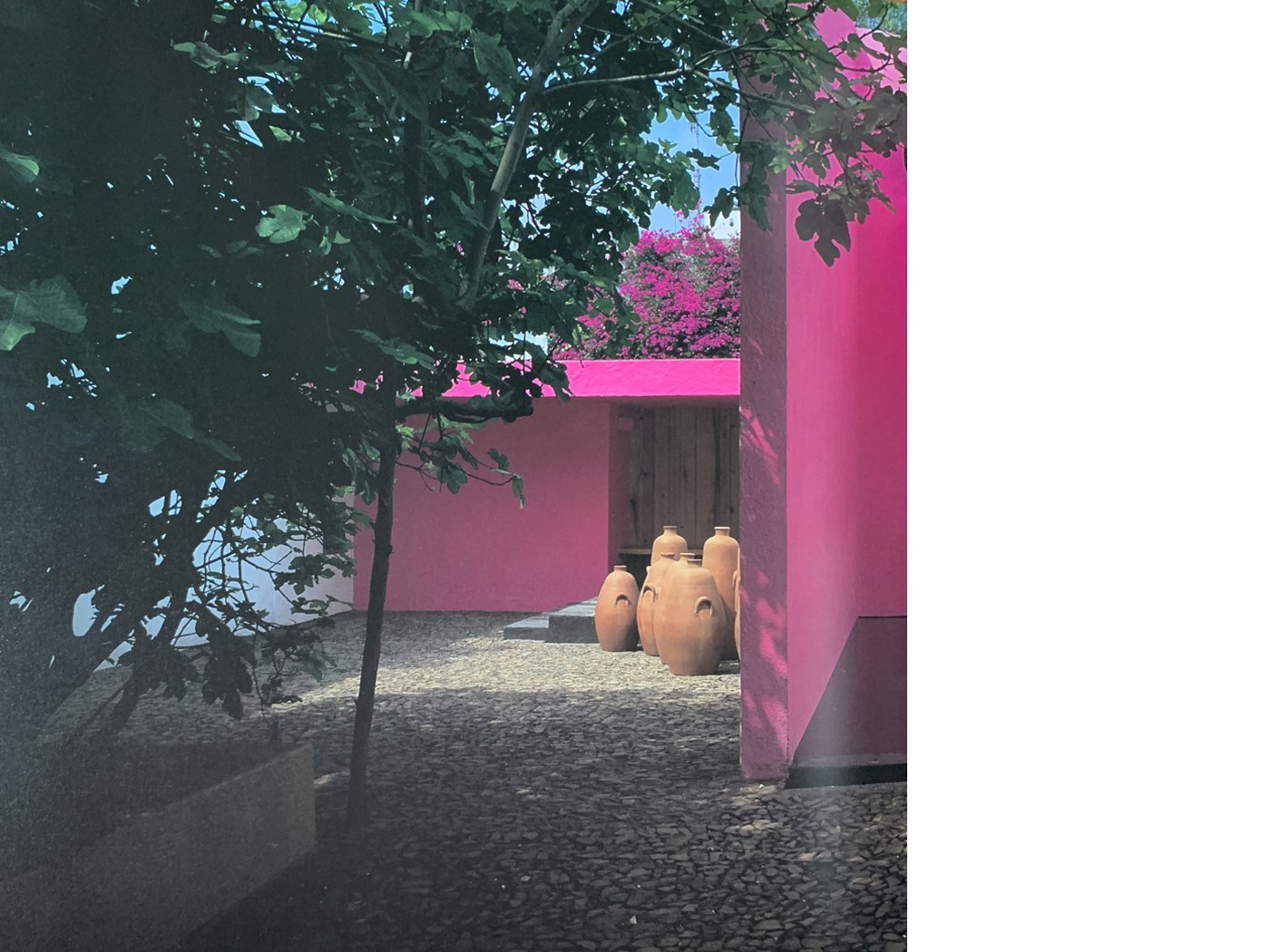

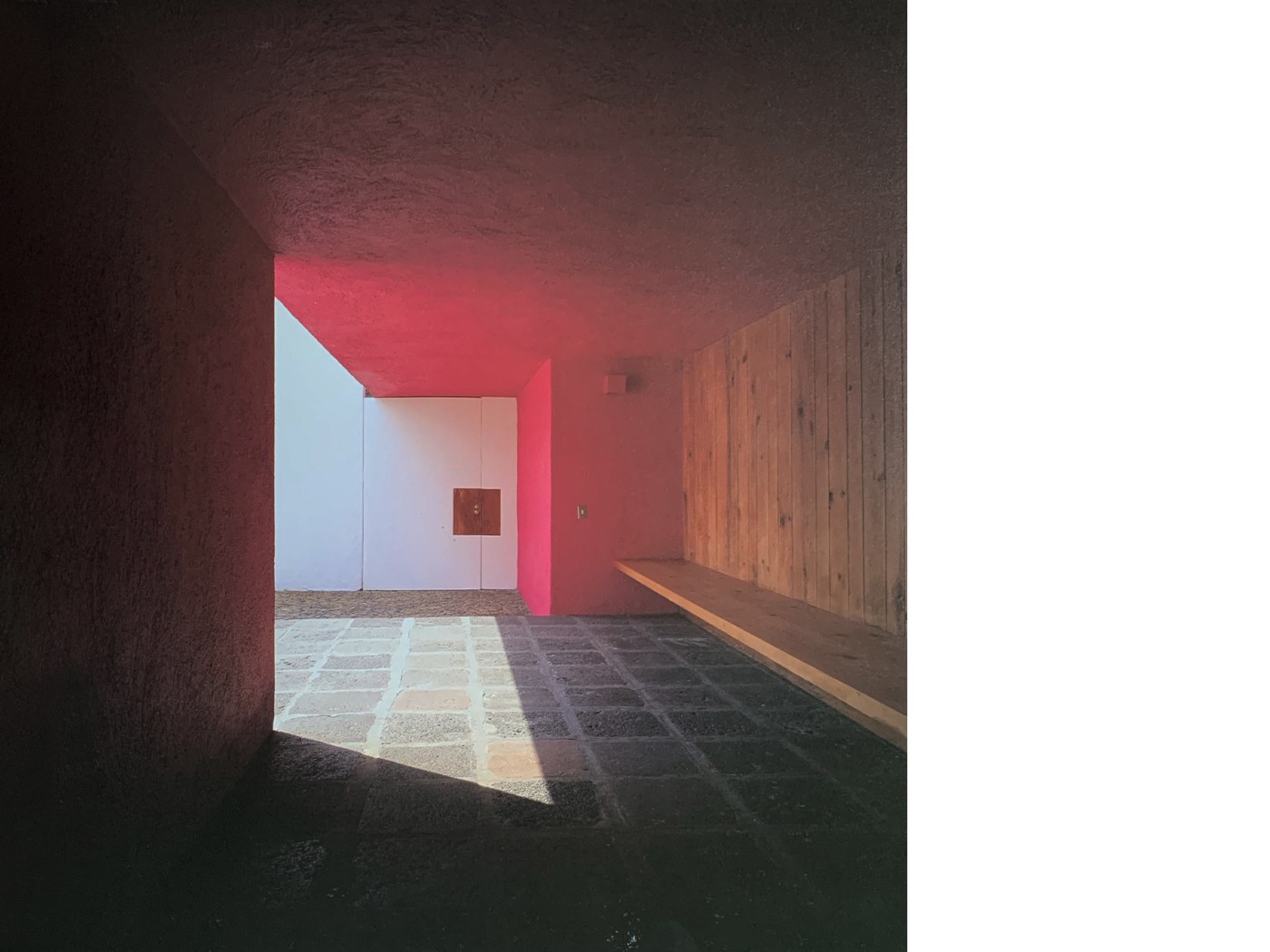

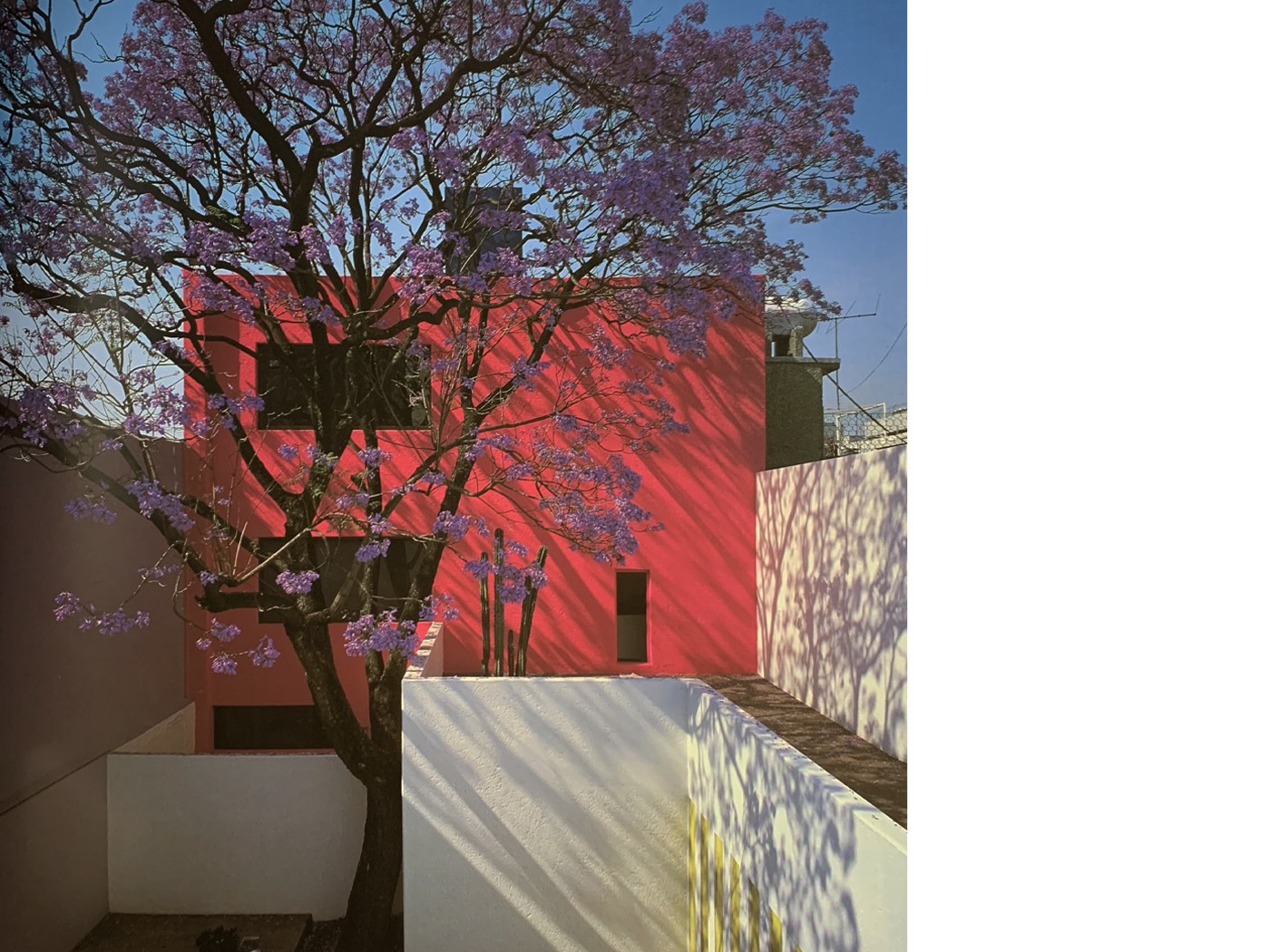

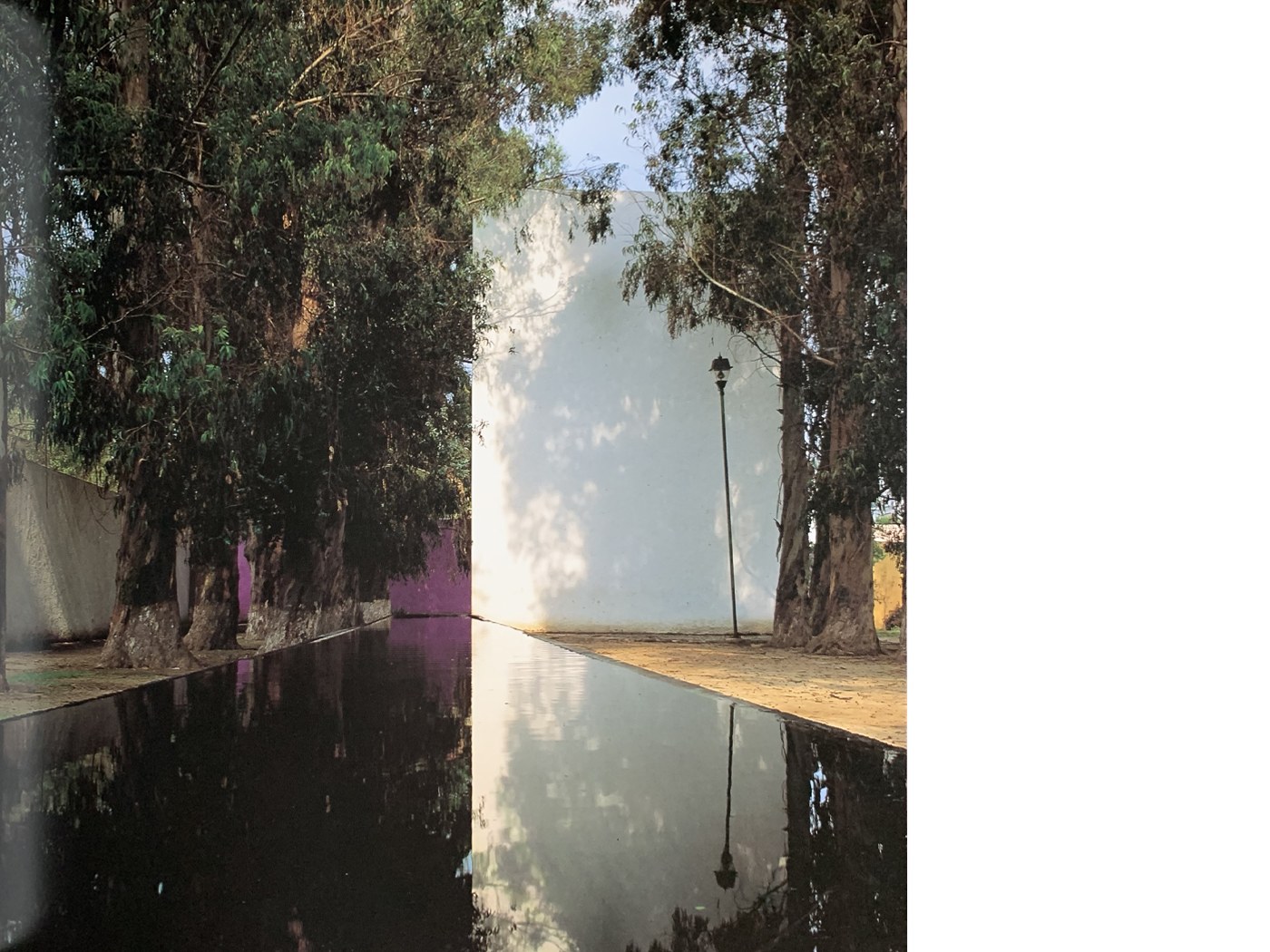

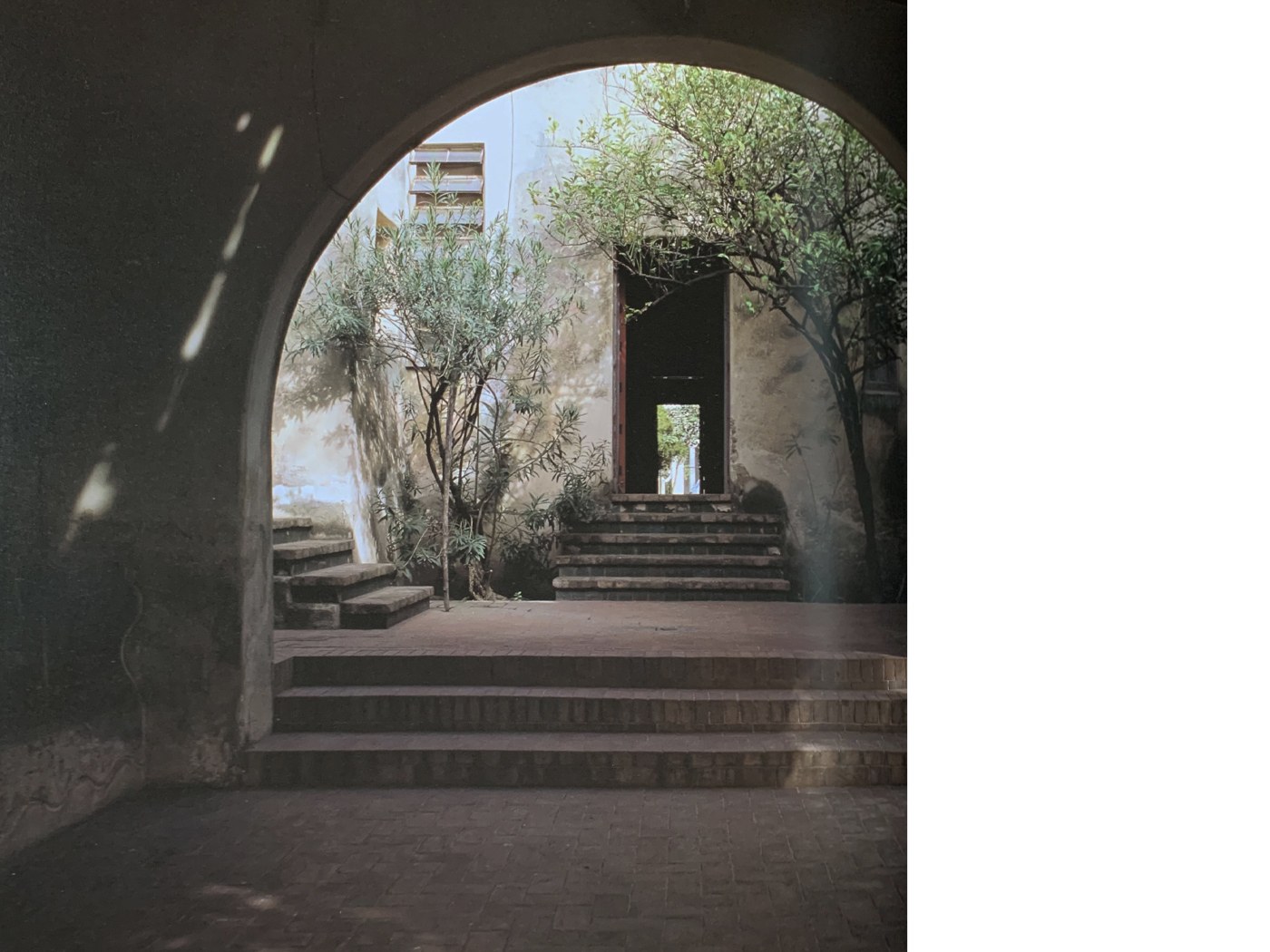

Some images from Yutaka Saito’s book on the work of Mexican architect Luis Barragán (1902-1988), to accompany eloquent words from his 1988 Pritzker Prize acceptance speech that have long deserved a place here:

It is alarming that publications devoted to architecture have banished from their pages the words Beauty, Inspiration, Magic, Spellbound, Enchantment, as well as the concepts of Serenity, Silence, Intimacy and Amazement. All these have nestled in my soul, and though I am fully aware that I have not done them complete justice in my work, they have never ceased to be my guiding lights.

Religion and Myth. It is impossible to understand Art and the glory of its history without avowing religious spirituality and the mythical roots that lead us to the very reason of being of the artistic phenomenon. Without the one or the other there would be no Egyptian pyramids or those of ancient Mexico. Would the Greek temples and Gothic cathedrals have existed? Would the amazing marvels of the Renaissance and the Baroque have come about?

Beauty. The invincible difficulty that the philosophers have in defining the meaning of this word is unequivocal proof of its ineffable mystery. Beauty speaks like an oracle, and ever since man has heeded its message in an infinite number of ways: it may be in the use of tattoos, in the choice of a seashell necklace by which the bride enhances the promise of her surrender, or, again, in the apparently superfluous ornamentation of everyday tools and domestic utensils, not to speak of temples and palaces and even, in our day, in the industrialized products of modern technology. Human life deprived of beauty is not worthy of being called so.

Silence. In the gardens and homes designed by me, I have always endeavoured to allow for the interior placid murmur of silence, and in my fountains, silence sings.

Solitude. Only in intimate communion with solitude may man find himself. Solitude is good company and my architecture is not for those who fear or shun it.

Serenity. Serenity is the great and true antidote against anguish and fear, and today, more than ever, it is the architect’s duty to make of it a permanent guest in the home, no matter how sumptuous or how humble. Throughout my work I have always strived to achieve serenity, but one must be on guard not to destroy it by the use of an indiscriminate palette.

Joy. How can one forget joy? I believe that a work of art reaches perfection when it conveys silent joy and serenity.

Death. The certainty of death is the spring of action and therefore of life, and in the implicit religious element in the work of art, life triumphs over death.

Gardens. In the creation of a garden, the architect invites the partnership of the Kingdom of Nature. In a beautiful garden, the majesty of Nature is ever present, but Nature reduced to human proportions and thus transformed into the most efficient haven against the aggressiveness of contemporary life. It will appear obvious, then, that a garden must combine the poetic and the mysterious with a feeling of serenity and joy. There is no fuller expression of vulgarity than a vulgar garden.

To the south of Mexico City lies a vast extension of volcanic rock, arid, overwhelmed by the beauty of this landscape, I decided to create a series of gardens to humanize, without destroying, its magic. While walking along the lava crevices, under the shadow of imposing ramparts of live rock, I suddenly discovered, to my astonishment, small secret green valleys the shepherds call them “jewels” surrounded and enclosed by the most fantastic, capricious rock formations wrought on soft, melted rock by the onslaught of powerful prehistoric winds. The unexpected discovery of these “jewels” gave me a sensation similar to the one experienced when, having walked through a dark and narrow tunnel of the Alhambra, I suddenly emerged into the serene, silent and solitary “Patio of the Myrtles” hidden in the entrails of that ancient palace. Somehow I had the feeling that it enclosed what a perfect garden no matter its size should enclose: nothing less than the entire Universe.

This memorable epiphany has always been with me, and it is not by mere chance that from the first garden for which I am responsible all those following are attempts to capture the echo of the immense lesson to be derived from the aesthetic wisdom of the Spanish Moors.

Fountains. A fountain brings us peace, joy and restful sensuality and reaches the epitome of its very essence when by its power to bewitch it will stir dreams of distant worlds.

Architecture. My architecture is autobiographical, as Emilio Ambasz pointed out in his book on my work published by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Underlying all that I have achieved, such as it, I share the memories of my father’s ranch where I spent my childhood and adolescence. In my work I have always strived to adapt to the needs of modern living the magic of those remote nostalgic years.

The lessons to be learned from the unassuming architecture of the village and provincial towns of my country have been a permanent source of inspiration. Such, for instance, the whitewashed walls; the peace to be found in patios and orchards; the colourful streets; the humble majesty of the village squares surrounded by shady open corridors. And as there is a deep historical link between these teachings and those of the North African and Moroccan Villages, they too have enriched my perception of beauty in architectural simplicity.

Being a Catholic, I have frequently visited with reverence the now empty monumental monastic buildings that we inherited from the powerful religious faith and architectural genius of our colonial ancestors, and I have always been deeply moved by the peace and wellbeing to be experienced in those uninhabited cloisters and solitary courts. How I have wished that these feelings may leave their mark on my work.

The Art of Seeing. It is essential to an architect to know how to see: I mean, to see in such a way that the vision is not overpowered by rational analysis.

Nostalgia. Nostalgia is the poetic awareness of our personal past, and since the artist’s own past is the mainspring of his creative potential, the architect must listen and heed his nostalgic revelations.

My associate and friend, the young architect Raul Ferrera, as well as our small staff, share with me the ideology that I have tried to present. We have worked and hope to continue to work inspired by the faith that the aesthetic truth of those ideas will in some measure contribute toward dignifying human existence.