iv 15

Villa Necchi Campiglio

To Milan for the furniture fair, and a visit to the Villa Necchi Campiglio. This urban villa was built on a large site amongst trees, surrounded by apartment blocks and colossal classical villas, by the prominent Milanese architect Piero Portaluppi (1888-1967), in 1932-35 with later alterations. It was built to a seemingly unlimited budget for a couple, Angelo and Gigina Campiglio, and her sister Nedda Necchi, heirs of a cast iron fortune. They were grand Milanese – guest bedrooms were kept for Italian minor royalty.

Gigina Necchi lived longest, and, childless (this would not have been a house for the relaxed raising of children), on her death in 2001 the house was left to FAI, the Italian equivalent of our National Trust, who have restored the house with a favouritism towards the principal architect Portaluppi. Sadly for the house the Necchi and Campiglio art collections were sold to form a charitable fund, and a number of original Portaluppi pieces of furniture designed for the house have left.

In Luca Guadagnino’s 2009 film I Am Love (Io Sono Amore) Tilda Swinton, despite her impeccable colour-blocked Jil Sander wardrobe, plays supporting role to the Villa itself, in a story written for it (I can only think of Simon Mawer’s novel The Glass Room, set around Mies van der Rohe’s Villa Tugendhat, as an example of a house as inspiration and protagonist), and which in course affirms my reservations about children around the Villa.

For a house to out-bill Tilda Swinton in Jil Sander it must be pretty strong, and this house is amazing and wondrous, but perhaps bears witness to the fact that, particularly with domestic work, architectural projects are the better for the collaboration of a good client. There is the sense, confirmed by the guides, that the family left Portaluppi to it, with stylistic and financial carta bianca. This is perhaps why, on completion, they almost immediately began altering Portaluppi’s work in favour of something more traditional.

Going around one tends to blank out the later overblown classical fireplaces, embroidered curtains and dainty classical furniture, but the truth is the house is a slightly uncomfortable mix of the work of two architects who, with the clients, were not part of one conversation. Portaluppi was the first; the second I cannot remember, and is not worthy of record (or Record).

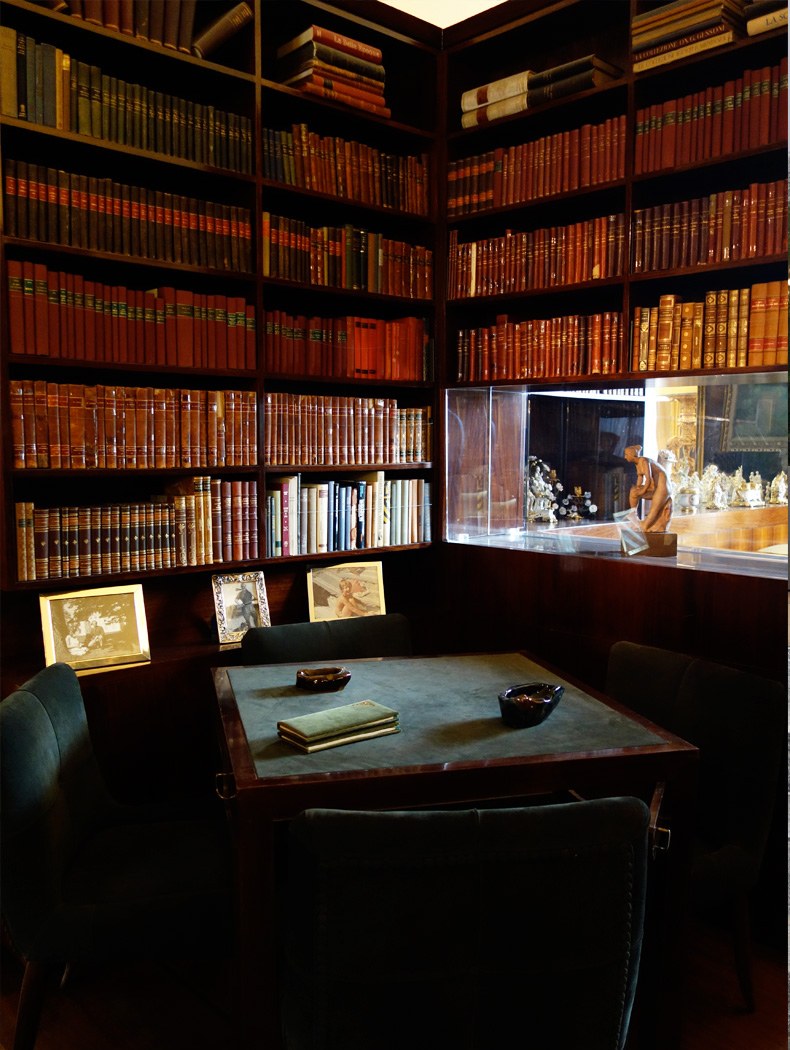

The original house is nonetheless a lavish exposition of the use of materials on a grand scale. Externally the building is faced in various stones with vast windows; internally, principal doors and the stair walls are lined in burr walnut, and the dining room in vellum; floors are in rare wide walnut boards with rosewood inlay; internal doors are around five metres high; external windows have a triplefold sliding system – single glazed, secondary double glazed and timber shuttered, which can be used in various combinations; the garden room has inner and outer glazed screens framed in brass with a heated winter garden between; the sliding security shutters closing this room are faced in German silver; bathrooms are formed in solid slabs of marble; radiator covers throughout have bespoke brass patterned covers.

But despite this and even in its unadulterated original form it was not perhaps a great work of architecture, or specifically of domestic architecture – it sits (perhaps dictated by the protected trees) awkwardly on its site, with the front door around the back and next to the swimming pool (only the second in Milan after the public baths), requiring the direction of the porter in his smart hut for the uninitiated visitor. Unless this was an intentional social device – I Am Love makes a pointed distinction between those who know the way and those that require direction – it is a failing; architecture should not require staff to direct users.

Internally, the plan displays little of the nuanced understanding of domestic architecture that distinguishes great houses – it lacks fluidity and is too reliant on doors rather than the subtleties of space to demark private or staff areas. The family’s bathrooms were lavish but are unwelcoming spaces that do not encourage lingering (to be fair to Portaluppi he was in uncharted ground here in 1935), and the bedrooms feel curiously exposed and so uncossetting, despite being accessed through two outer rooms. Fellow-tourees wowed at the marble and steel back staff stair but to my mind it looked a dangerous climb, which would be made perilous with a tea tray in hand, and better suited to the office buildings with which Portaluppi was more familiar. It is perhaps this unease which the owners felt and which caused them to seek another hand.

But thinking about it, the villa has all the qualities of Milan as a city. Lavish, schizophrenically grand classical and stripped modern, built on a grand scale, curiously unwelcoming, and disorientating however many times you visit, so perhaps it is not so unsophisticated a work of architecture as I depict.