viii 18

Rules of Style

An interview on style for MatchesFashion.com

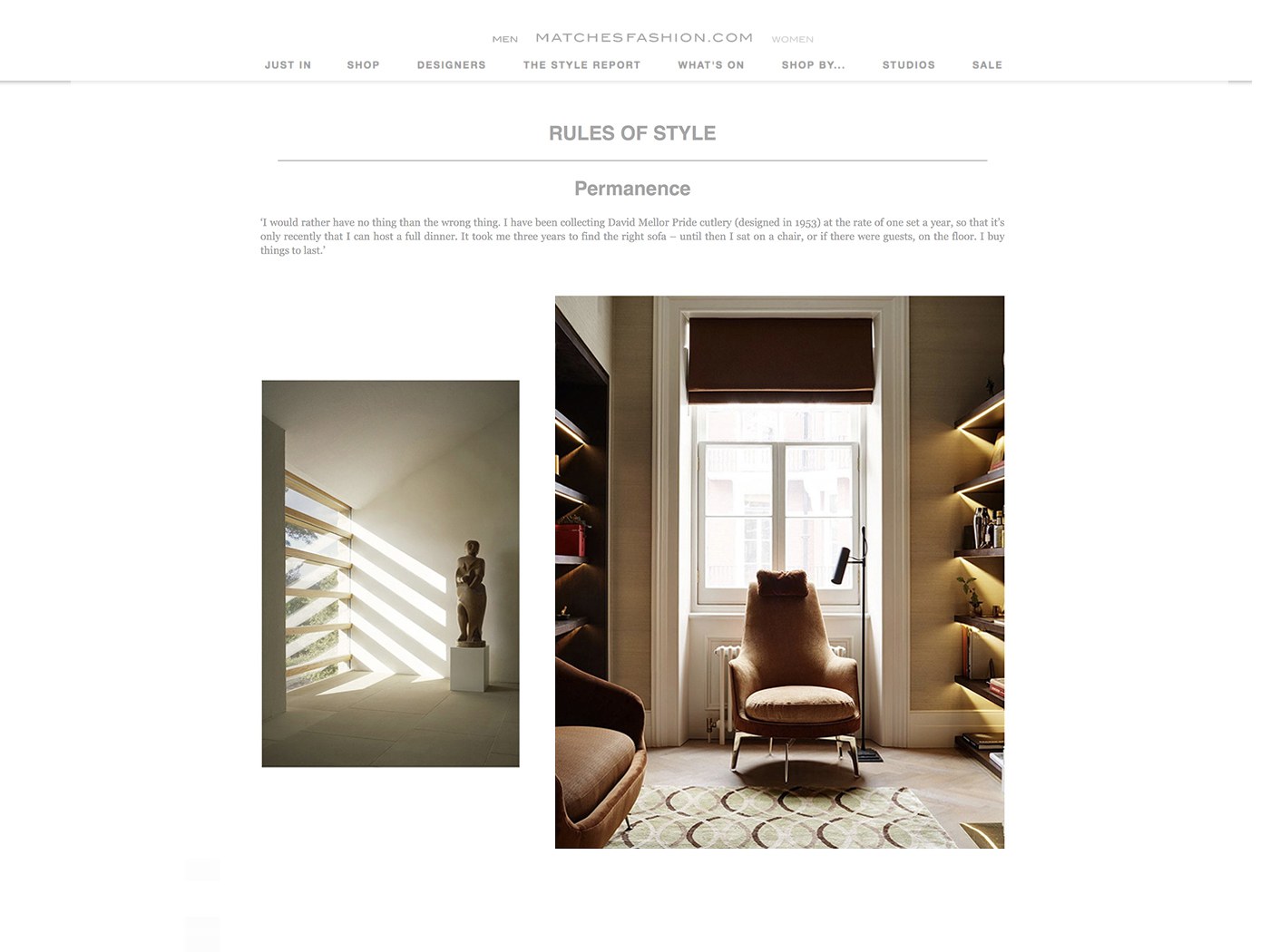

Permanence

‘I would rather have no thing than the wrong thing. I have been collecting David Mellor Pride cutlery (designed in 1953) at the rate of one set a year, so that it’s only recently that I can host a full dinner. It took me three years to find the right sofa – until then I sat on a chair, or if there were guests, on the floor. I buy things to last.’

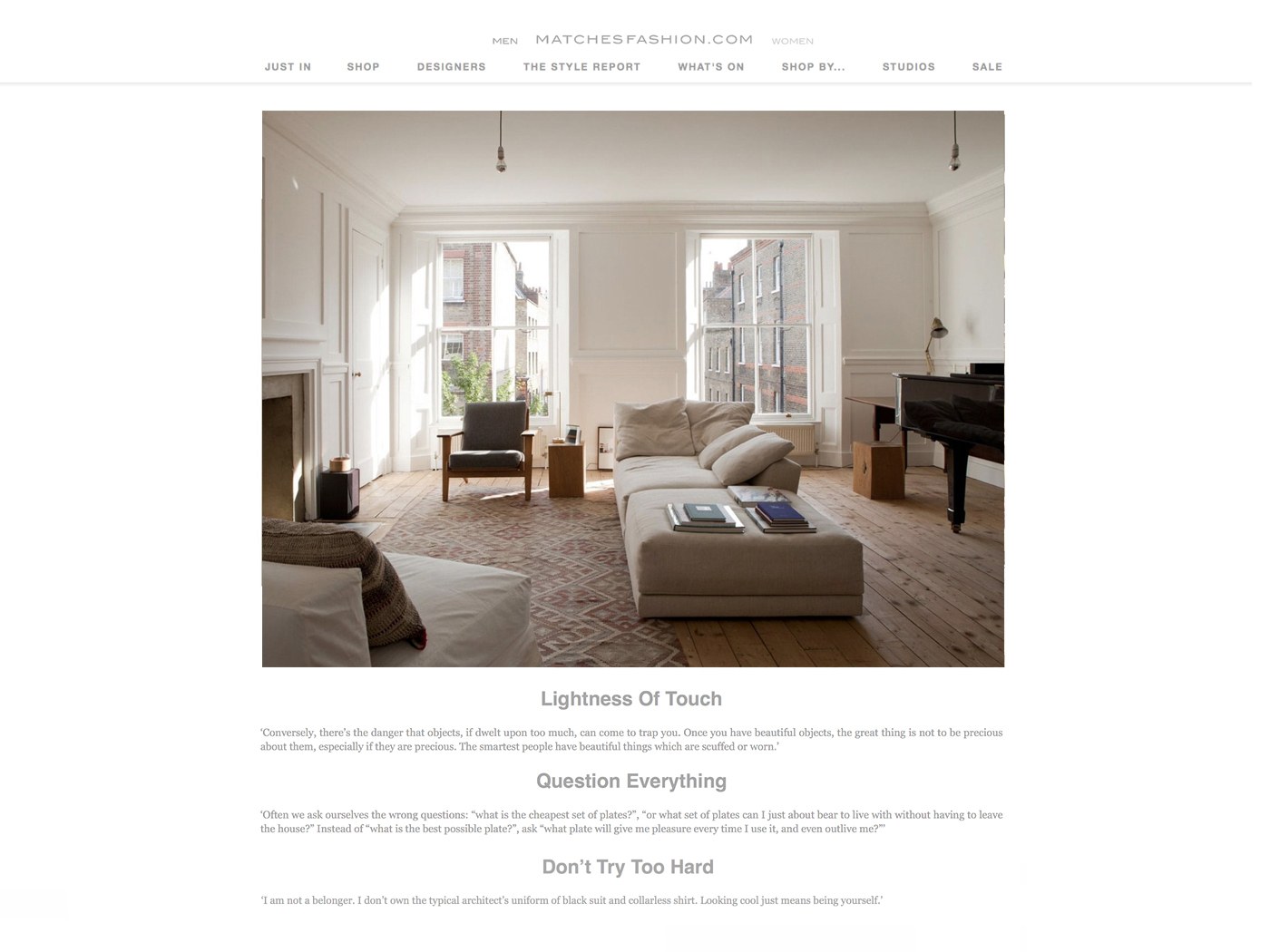

Lightness Of Touch

‘Conversely, there’s the danger that objects, if dwelt upon too much, can come to trap you. Once you have beautiful objects, the great thing is not to be precious about them, especially if they are precious. The smartest people have beautiful things which are scuffed or worn.’

Question Everything

‘Often we ask ourselves the wrong questions: instead of asking “What is the cheapest set of plates?” or “What set of plates can I just about bear to live with without having to leave the house?” we should ask “What is the best possible plate?”, or “What plate will give me pleasure every time I use it, and even outlive me?”’

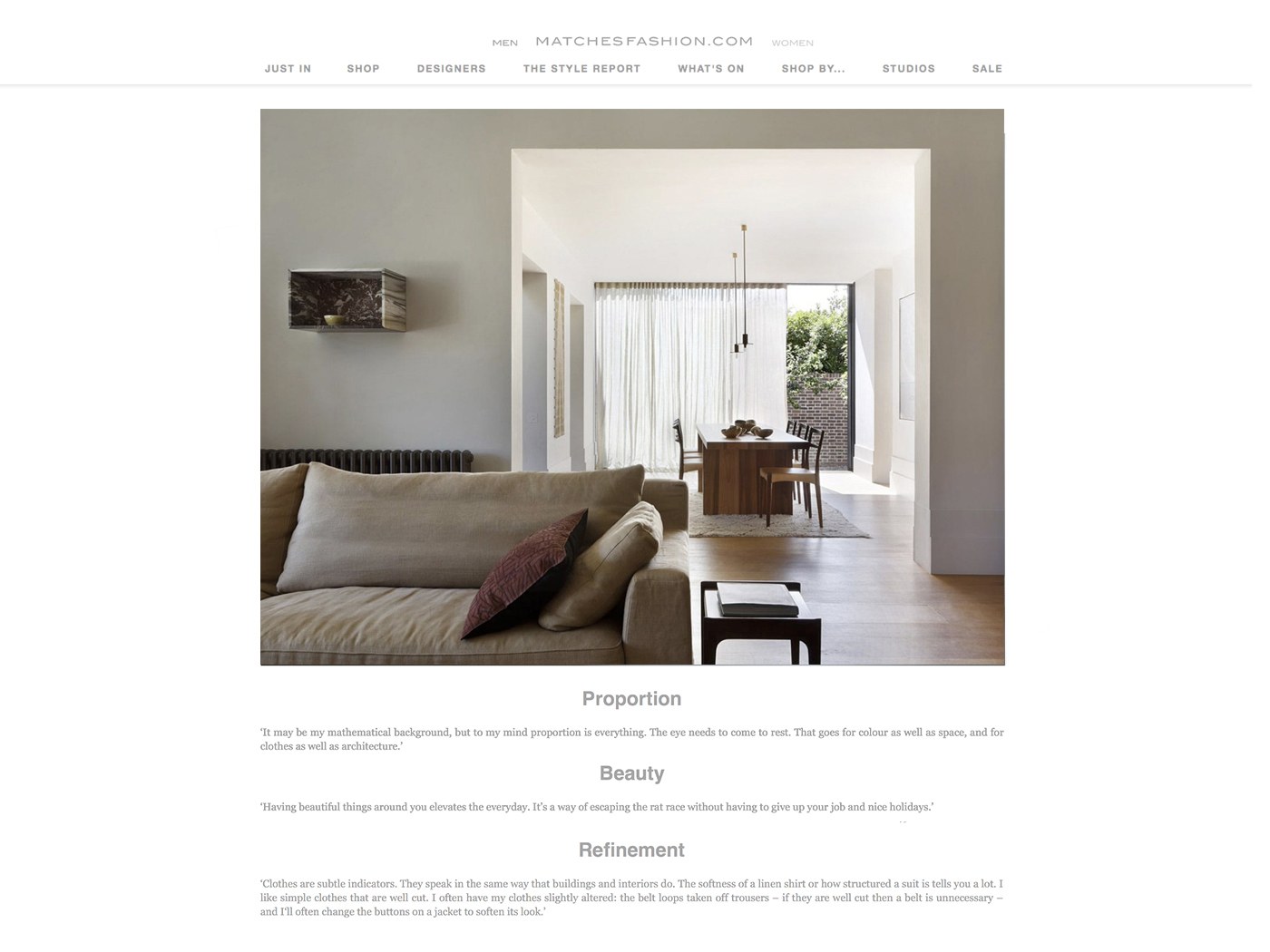

Proportion

‘It may be my mathematical background, but to my mind proportion is everything. The eye needs to come to rest. That goes for colour as well as space, and for clothes as well as architecture.’

Beauty

‘Having beautiful things around you elevates the everyday. It’s a way of escaping the rat race without having to give up your job and nice holidays.’

Things Made Well

‘Things done well in any walk of life make me well up, and well-designed and made objects hold that emotion for me. Maybe that’s why I like objects that bear the mark of their maker. There should be a word for it, a sort of visual onomatopoeia.’

Refinement

‘Clothes are subtle indicators. They speak in the same way that buildings and interiors do. The softness of a linen shirt or how structured a suit is tells you a lot. I like simple clothes that are well cut. I often have my clothes slightly altered: the belt loops taken off trousers – if they are well cut then a belt is unnecessary – and I‘ll often change the buttons on a jacket to soften its look.’

Don’t Try Too Hard

‘I am not a belonger. I don’t own the typical architect’s uniform of black suit and collarless shirt. Looking cool just means being yourself.’

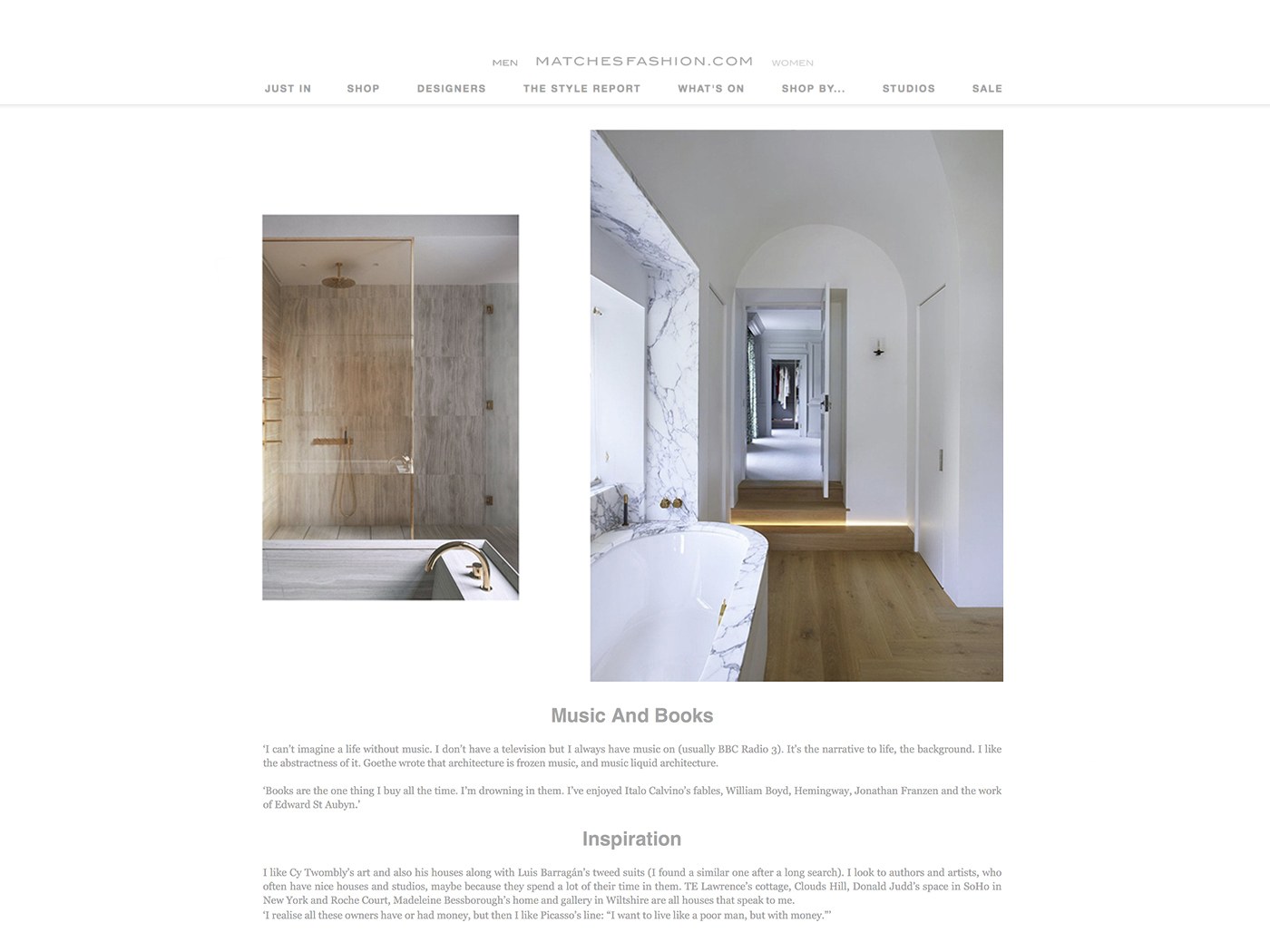

Music And Books

‘I can’t imagine a life without music. I don’t have a television but I always have music on (usually BBC Radio 3). It’s the narrative to life, the background. I like the abstractness of it. Goethe wrote that architecture is frozen music, and music liquid architecture.

Books are the one thing I buy all the time. I’m drowning in them. I’ve enjoyed Italo Calvino’s fables, William Boyd, Hemingway, Jonathan Franzen and the work of Edward St Aubyn.’

Inspiration

‘I like Cy Twombly’s art and also his houses along with Luis Barragán’s tweed suits (I found a similar one after a long search). I look to authors and artists, who often have nice houses and studios, maybe because they spend a lot of their time in them. TE Lawrence’s cottage, Clouds Hill, Donald Judd’s space in SoHo in New York and Roche Court, Madeleine Bessborough’s home and gallery in Wiltshire are all houses that speak to me.

‘I realise all these owners have or had money, but then I like Picasso’s line: “I want to live like a poor man, but with money.”’

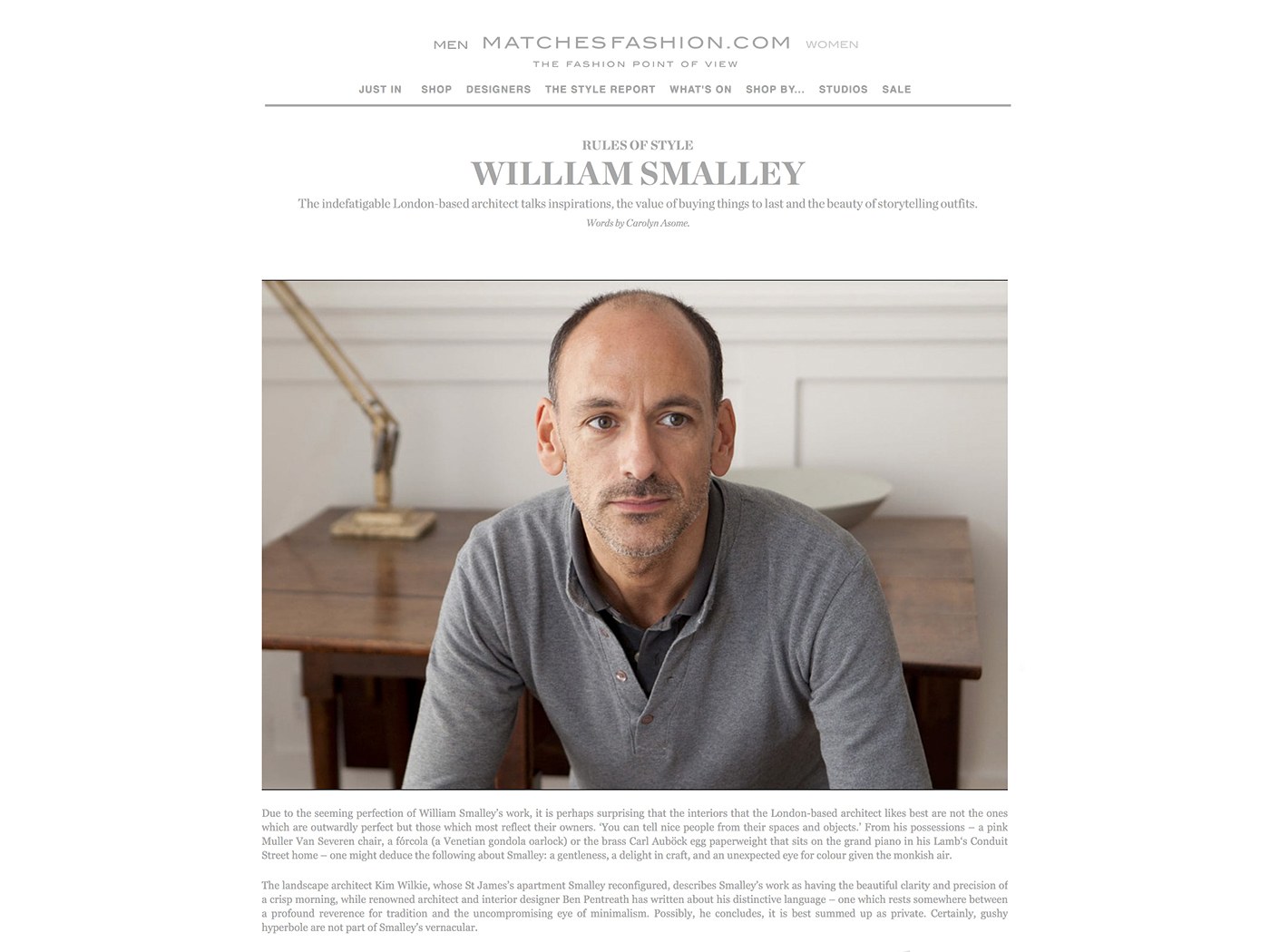

Due to the seeming perfection of William Smalley’s work, it is perhaps surprising that the interiors that the London-based architect likes best are not the ones which are outwardly perfect but those which most reflect their owners. ‘You can tell nice people from their spaces and objects.’ From his possessions – a pink Muller Van Severen chair, a fórcola (a Venetian gondola oarlock) or the brass Carl Auböck egg paperweight that sits on the grand piano in his Lamb‘s Conduit Street home – one might deduce the following about Smalley: a gentleness, a delight in craft, and an unexpected eye for colour given the monkish air.

The landscape architect Kim Wilkie, whose St James’s apartment Smalley reconfigured, describes Smalley’s work as having the beautiful clarity and precision of a crisp morning, while renowned architect and interior designer Ben Pentreath has written about his distinctive language – one which rests somewhere between a profound reverence for tradition and the uncompromising eye of minimalism. Possibly, he concludes, it is best summed up as private. Certainly, gushy hyperbole are not part of Smalley’s vernacular.

‘I like anything that is plain and stripped back,’ he says. ‘Architecture is my way into everything, I dream in buildings’ – something he has been doing since he was a boy when he was skipping games lessons to sit inside and draw. Smalley’s grandfather was a mathematician who taught Alan Turing at Cambridge and his mother was a computer programmer in the 1960s. His parents were never going to let him become a solicitor or a banker but, in any case, the architectural die was already cast.

His first client was Alan Rusbridger, the former editor of The Guardian whose weekend cottage he remodelled in the Cotswolds. More recently, he completed the Monocle’s editor’s London house and a London townhouse, known as Disco House, which appeared in Wallpaper* with its mid-century feel and play on materials. His projects – he works on 10 to 12 at any one time – are as varied as an ancient English country house, a modernist house on Ham Common, an apartment in Manhattan and a chateau in the French Alps (he took the roof off to install a 2,500sq ft party floor).

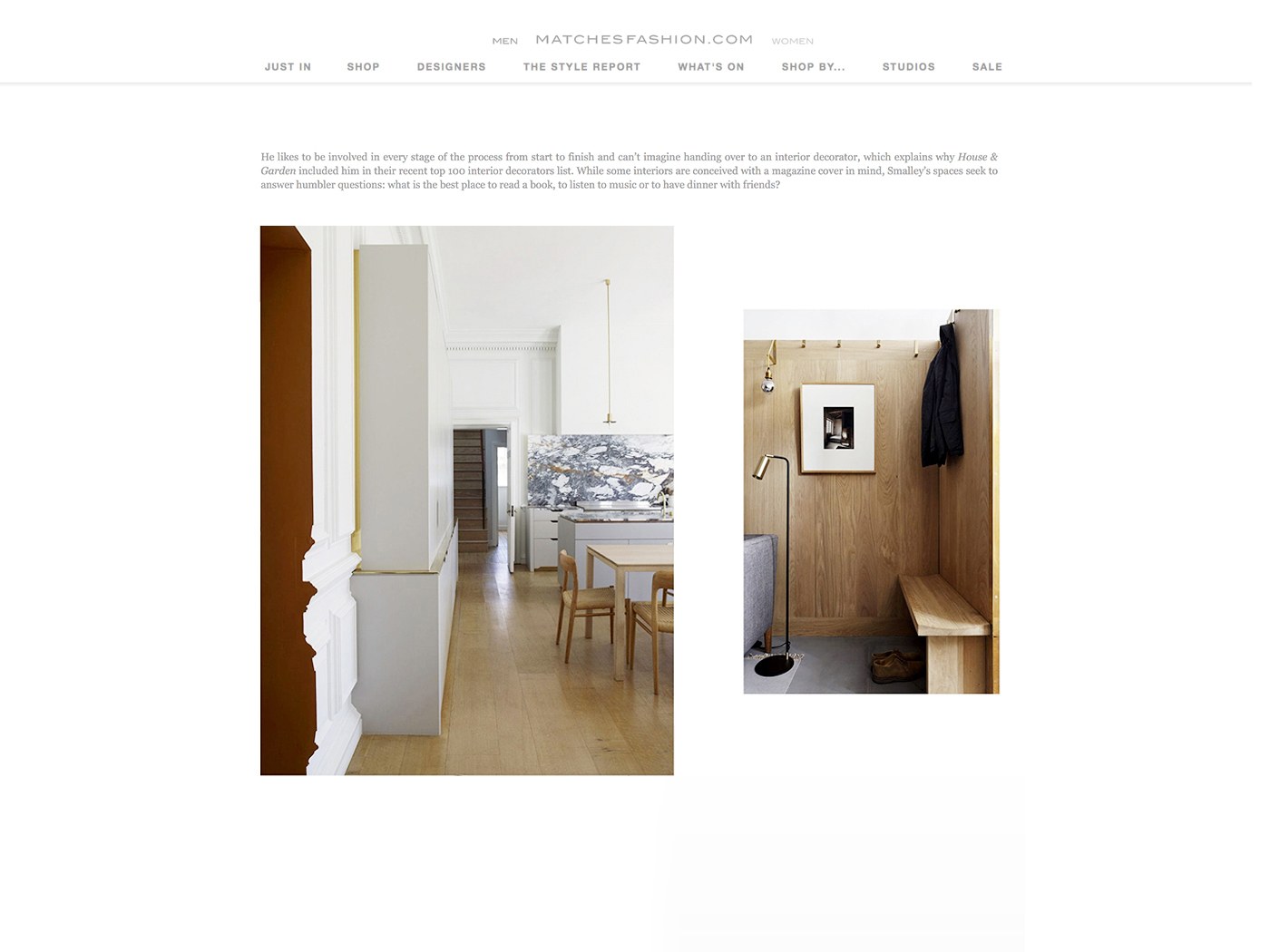

He likes to be involved in every stage of the process from start to finish and can’t imagine handing over to an interior decorator, which explains why House & Garden included him in their recent top 100 interior decorators list. While some interiors are conceived with a magazine cover in mind, Smalley’s spaces seek to answer humbler questions: what is the best place to read a book, to listen to music or to have dinner with friends?

text: Carolyn Asome