vi 15

Cornices in Utopia

I went the other day for a meeting with a client who is living temporarily in a flat while their house is worked on. The flat is on the top floor of a ’60s block, not quite a tower at eight storeys high, in west London. The flat is remarkable for its wonderful roof- and tree- top views, but otherwise is a not particularly ambitious piece of English Modernism, although thought clearly went into it – it is amazing how quickly Modernism became a universal architectural language.

It struck me as poignant to imagine its building committee – one imagines be-pearled west London widows living there because it is terribly practical (lift, all on one level, no garden to maintain) – collectively agreeing that the common parts just don’t look quite finished without a cornice, and the builder choosing one from a catalogue (do you choose the Georgian, Regency or Victorian to go with Modernism?). And once there is a cornice, marble-effect wallpaper is just the logical committee quorum away.

The Modernism that begat that block was a political movement that has all but fizzled out. Its wholehearted adoption by town planners and local authority architects wrecked such cruel pain on poor English market towns and cities that had simply asked for a bit of car parking, and imposed so alien an aesthetic and mode of living on people who had not chosen it, that it became untrusted, and failed.

Terence Davies’ 2008 documentary film Of Time and the City, collated from BBC archive footage of Liverpool, poignantly contrasts scrubbed proud front steps of Liverpool terraces with the abstract notion of net curtains hanging twenty stories up, as if the petticoats of the housewives had been strung up; since watching that sequence I have looked at tower blocks as I would a disgraced dictator, or Shirley Porter.

Any creed – political, religious or aesthetic – which believes it has all the answers is by definition wrong, and so Modernism was too sure of itself, not allowing for the possibility that it might be over-stridently convinced of its rightness. Some self-reflection would have allowed it to endure, as it has in Scandinavia.

Instead, as each arrogantly inept local authority tower and the non-community it has engendered around it collapses, another piece of the Modernist dream has died, but at the other end of the property scale the result in Britain today is a very sad thing: in this country if you make some money and want to build a house to show it, you build a classical house – generally badly (since it will inevitably be a fake), and always with your feet planted firmly looking backwards. This almost inalienable fact angers me almost as much as it saddens me. What does it say about our faith in and hopes for the future?

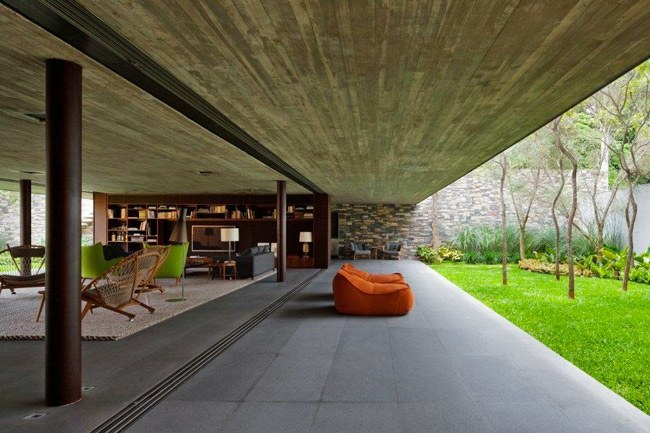

You couldn’t imagine a Brazilian entrepreneur doing the same – look at the work of Marcio Kogan’s office MK27, the output of which alone outstrips the entire oeuvre of good modern houses in the UK. There are very few good contemporary houses here to inspire, that suit our wet climate and which respond to the British character. This in turn discourages potential commissioners of modern houses, causes them to understandably err on the side of timidity, and decide they will instead just add a bit of interest with some mid-century furniture in the hall and a B&B sofa in the TV room.

The bravery, ambition and optimism of commissioning a New house, to take the chance that things might not work as you expected, and that might challenge your idea of home, seem to have gone, and been replaced by nostalgia, and the cosy familiarity of a cornice in the hall.