ii 26

Writing Quiet Spaces

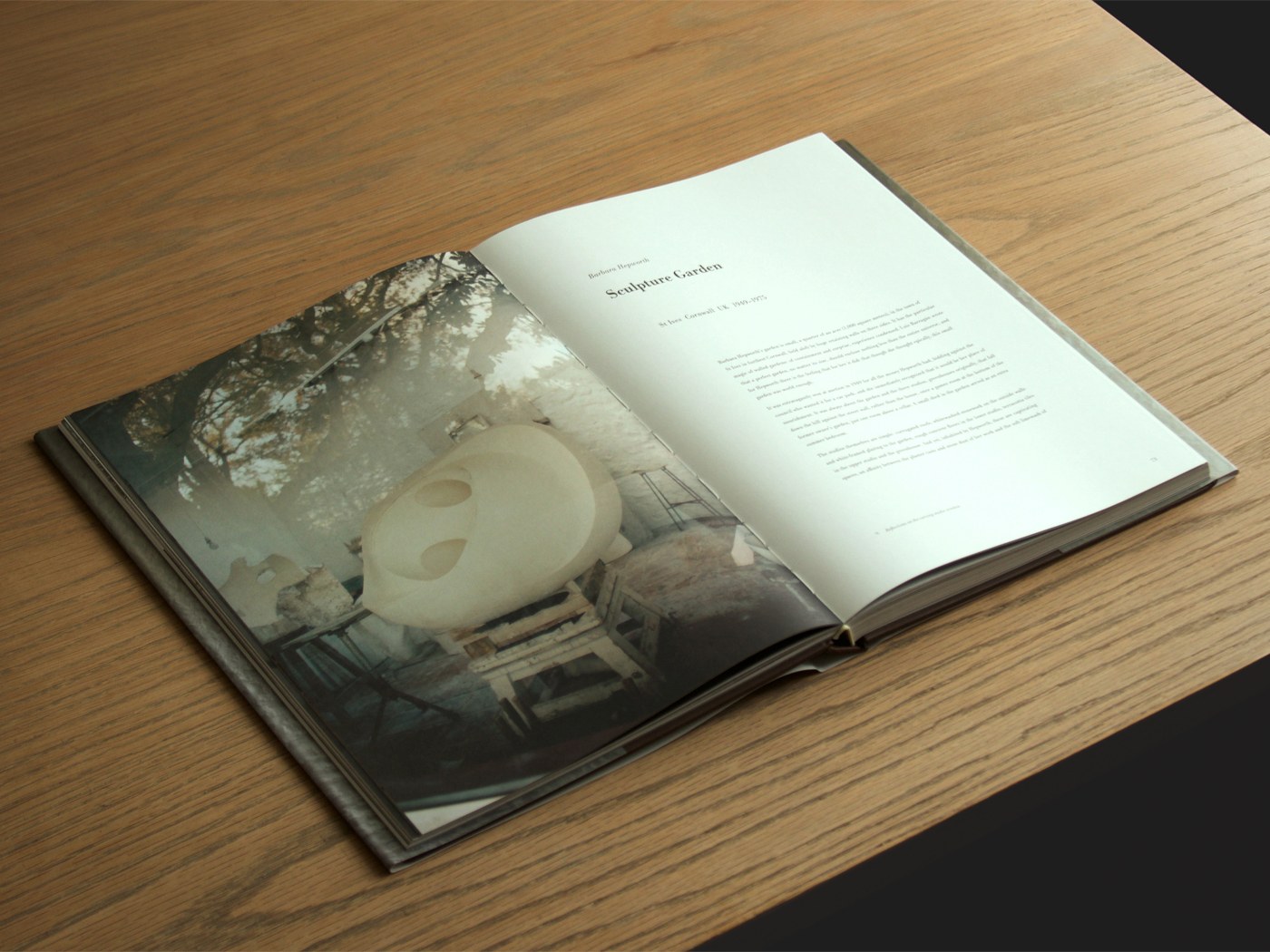

I have had a postcard of Barbara Hepworth’s studio on my desk since I started the studio. Stone and plaster sculptures in front of a whitewashed rubblestone wall, under toplight. I don’t really question it, but I think it is there as a reminder of the importance of doing, and of the importance of allowing the doing to be recorded, not hidden away.

—

I always wanted to write a book. I think of it as part of the practice of architecture. Not as a substitute for building, but as a recording of things other than the actual building, for people other than the buildings’ inhabitants. I imagined a book about more than the studio’s work, to be read not just by architects.

Quiet Spaces was many years in the conceiving, pitching, shooting, writing, editing and printing. It takes a long time. I am fortunate author is not my job.

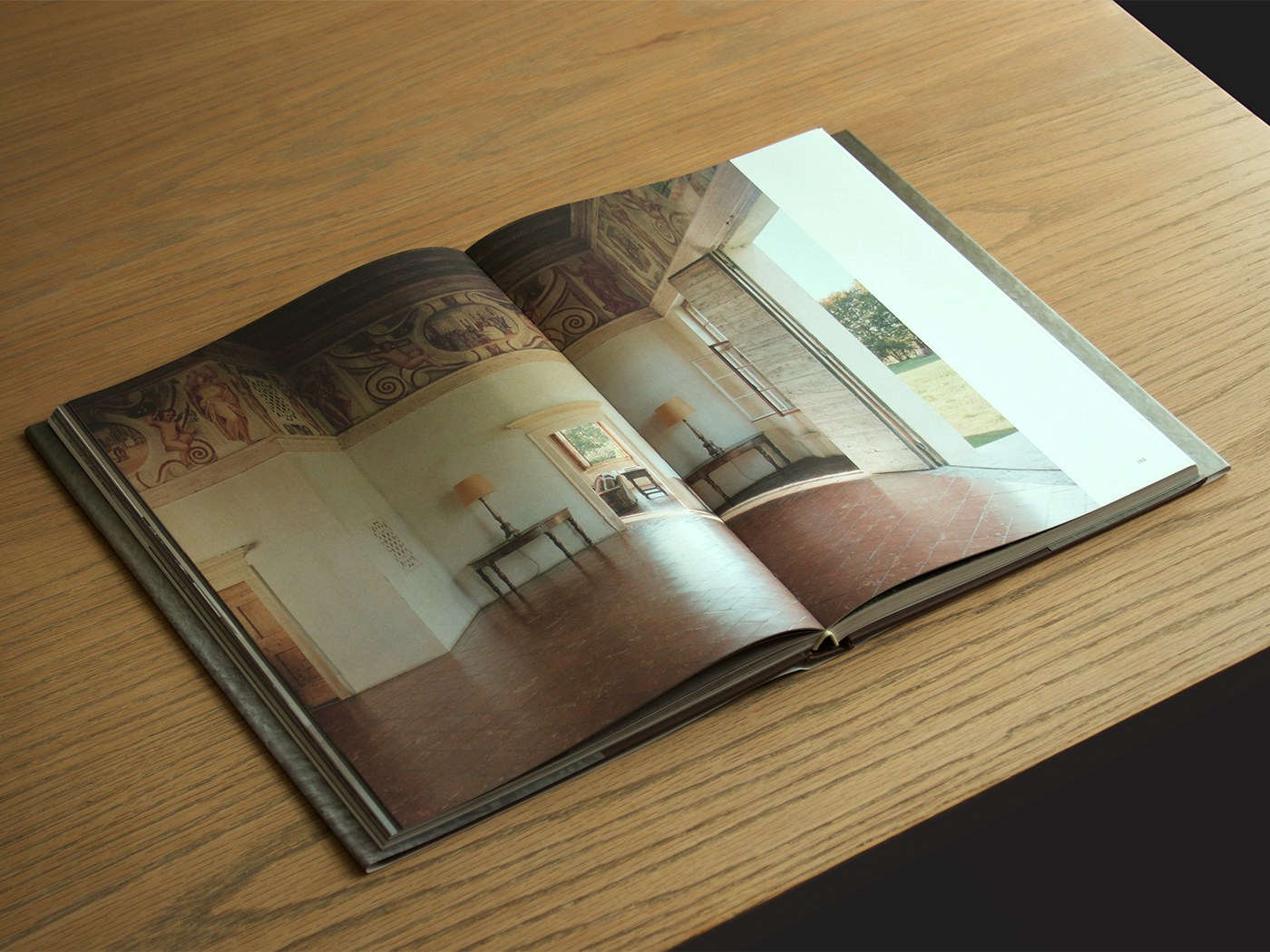

Working out the format took the first year. The book covers sixteen places: eight of the studio’s projects, some new and some re-shot; and eight places of inspiration, places that I return to, in person, in books, in my mind. Houses, gardens, galleries, studios, spanning five hundred years, from Palladio’s Villa Saraceno in the Veneto built in 1554, to Peter Zumthor’s Secular Retreat built for Living Architecture in 2018. An early reader said that he saw a generosity in allowing the works of others into the book, but it felt natural to me; just as in architecture there is a continuum of time, there is of influence. Taken together the spaces speak of purity, an interest in modernity and progress, in landscape and settings, in serenity, the irrelevance of time, and a slight otherness. The word floating reappears.

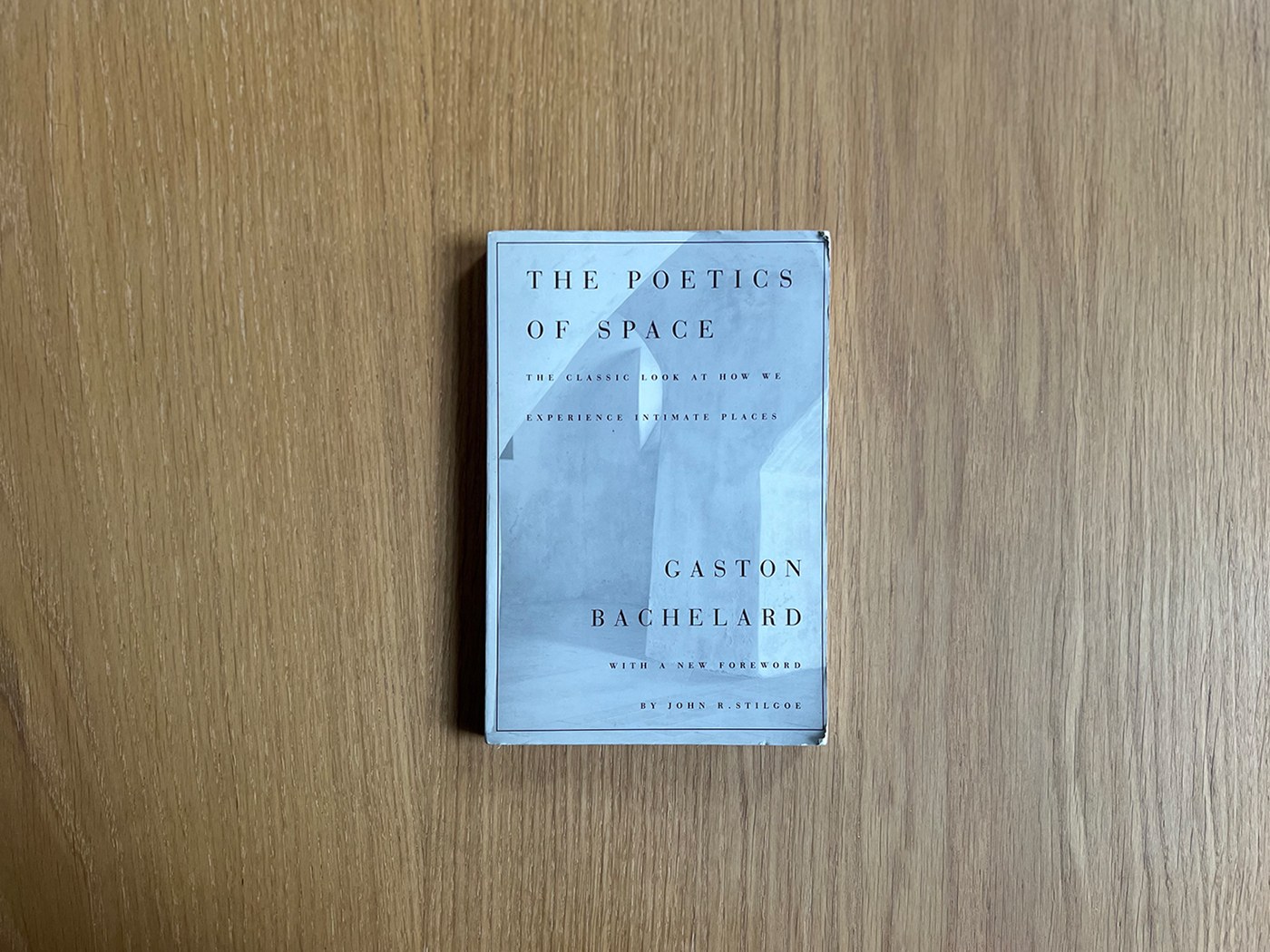

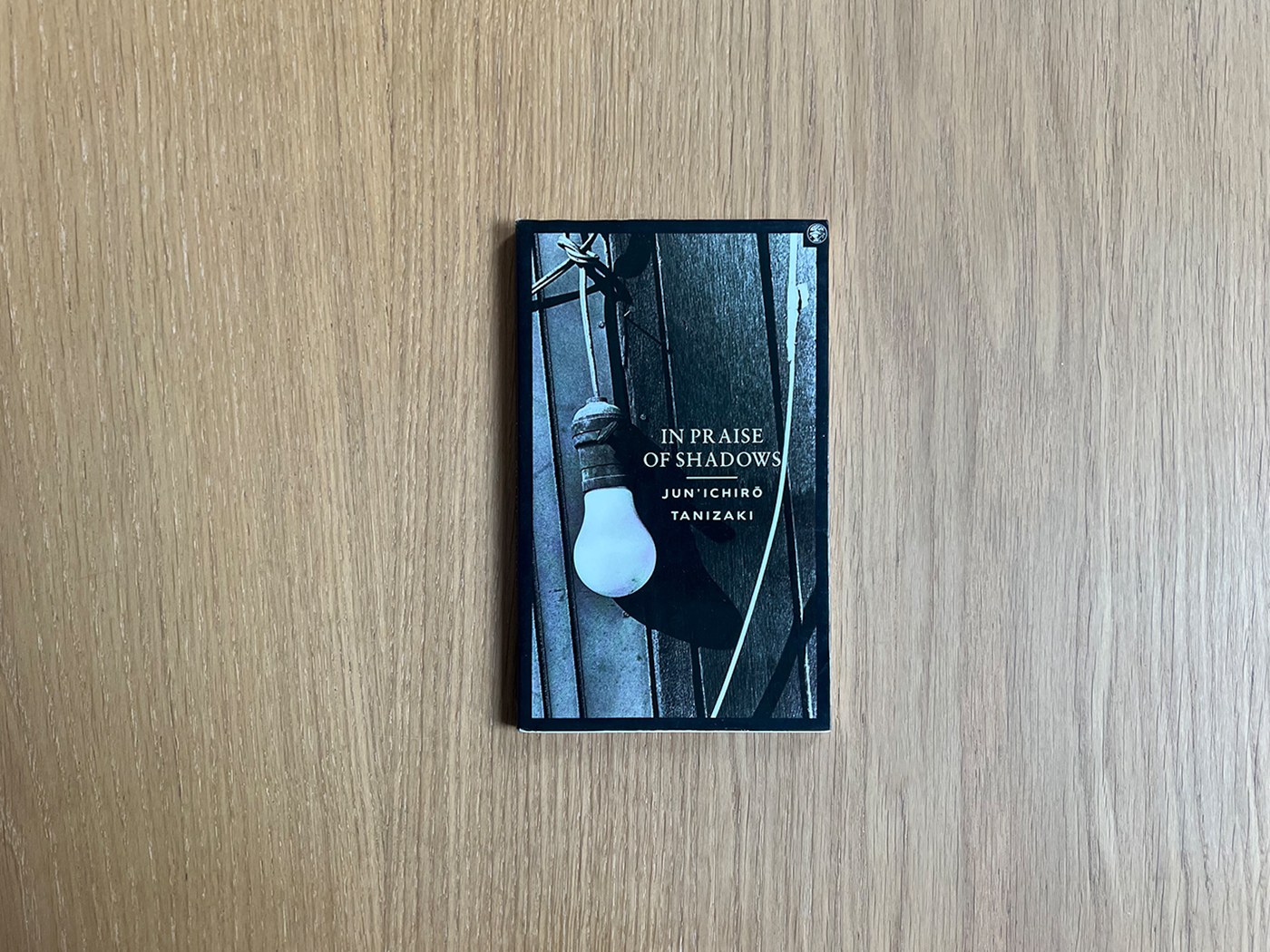

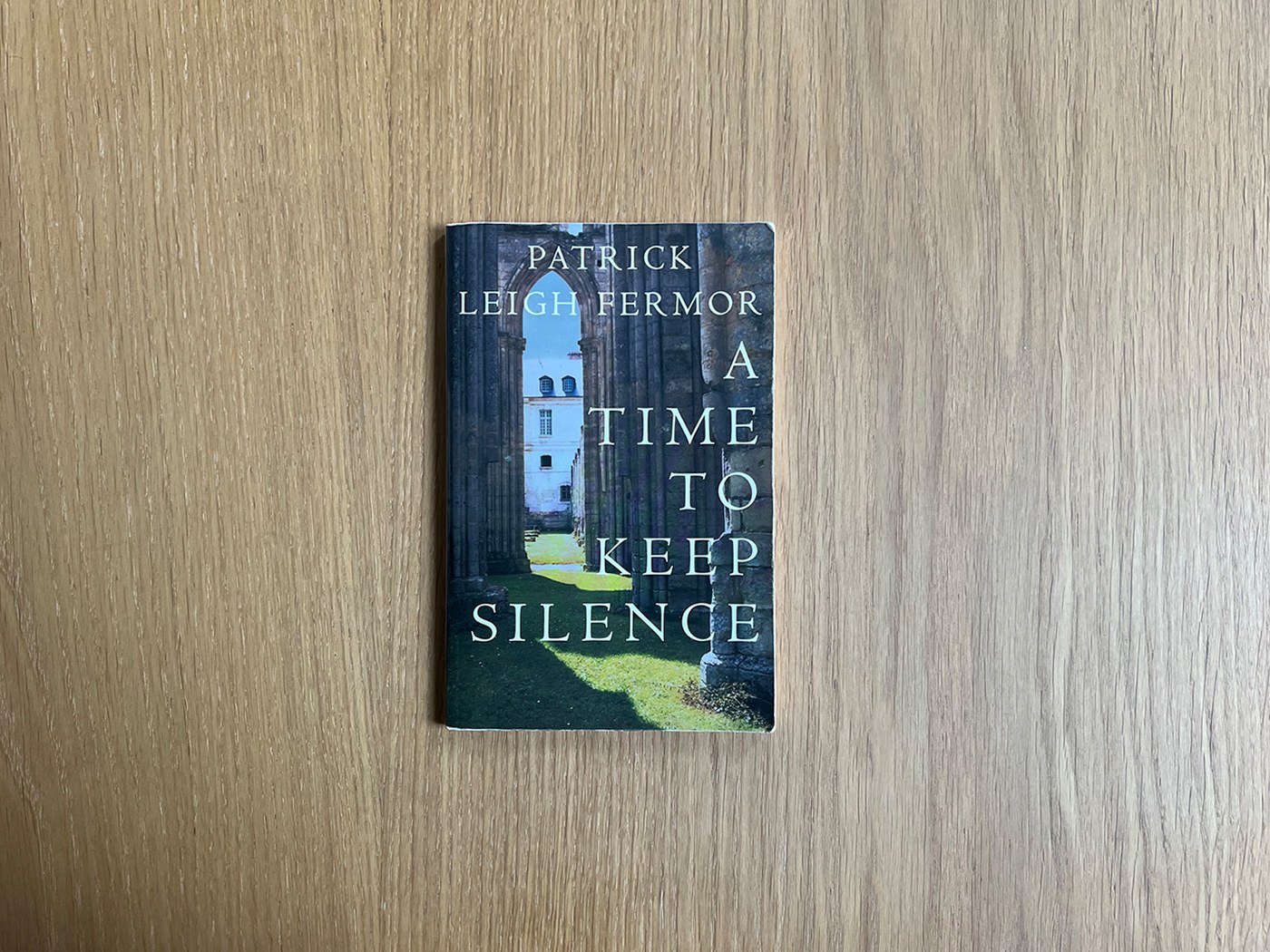

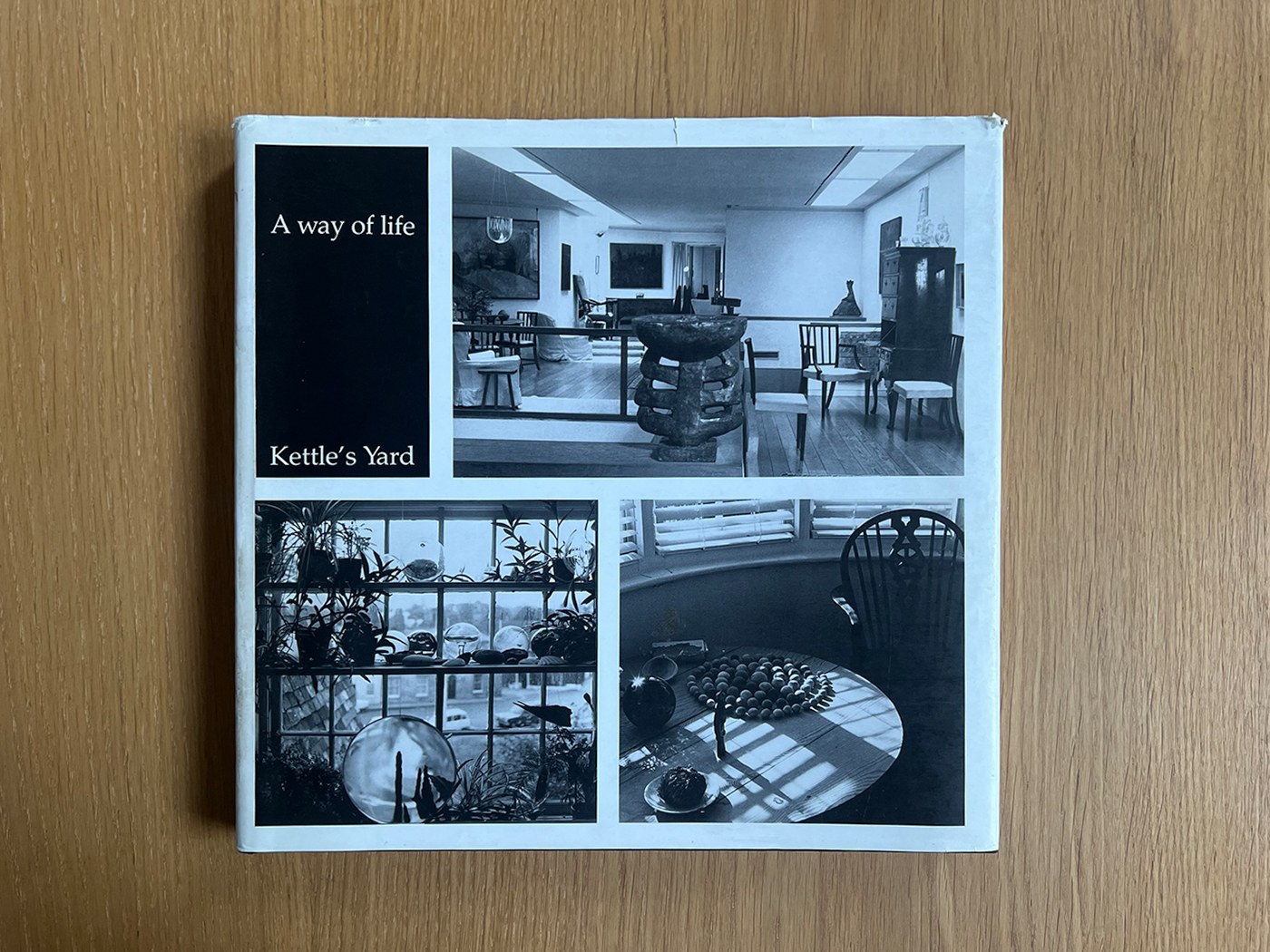

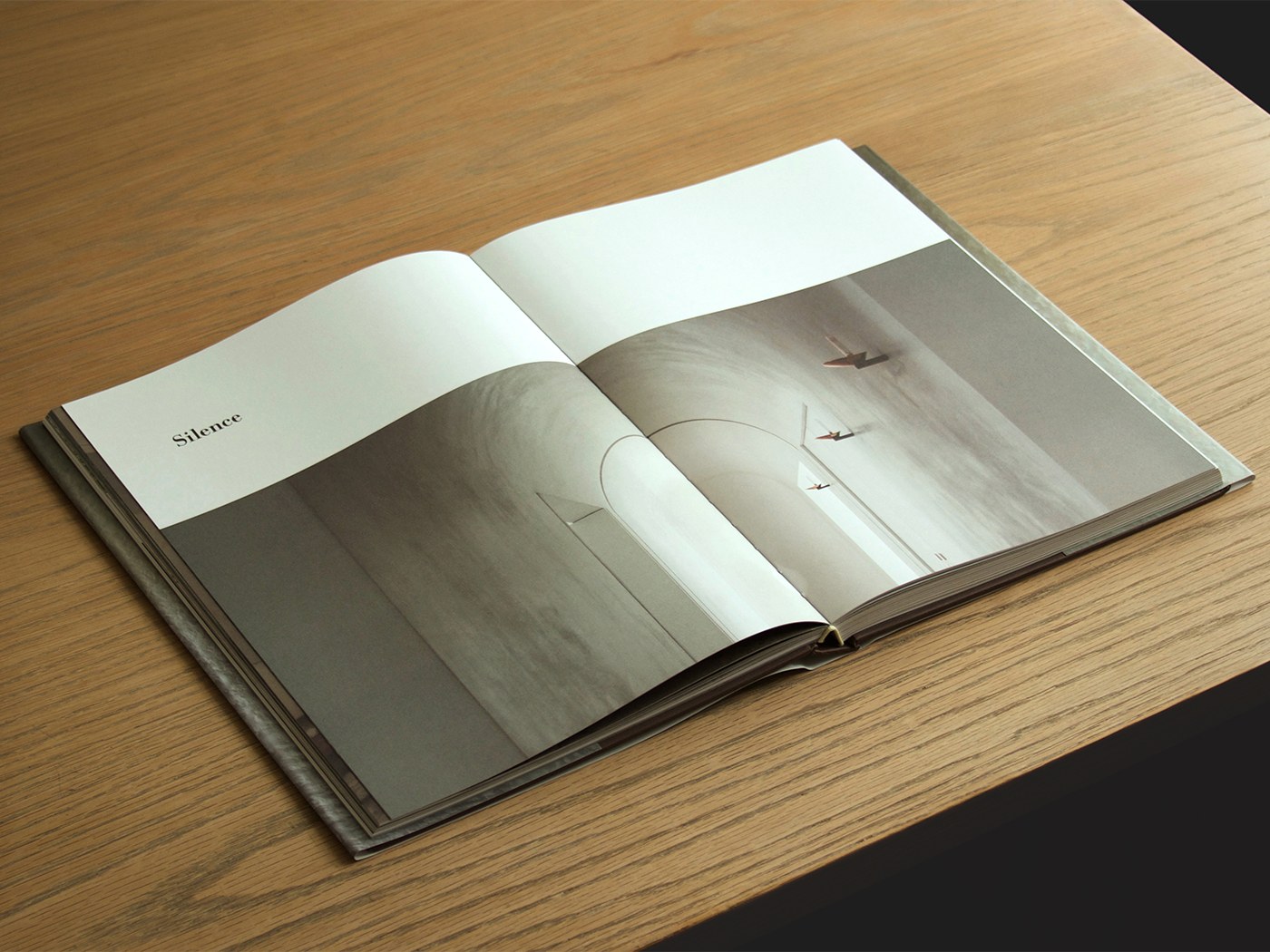

Naming the chapters they are grouped into, four themes running through the book, took another year. They came, in the end, from four books that a colleague in the studio noted I was always referring to. I carried them around with me for the next few years, reading them on waking, on flights and in hotel rooms, absorbing them.

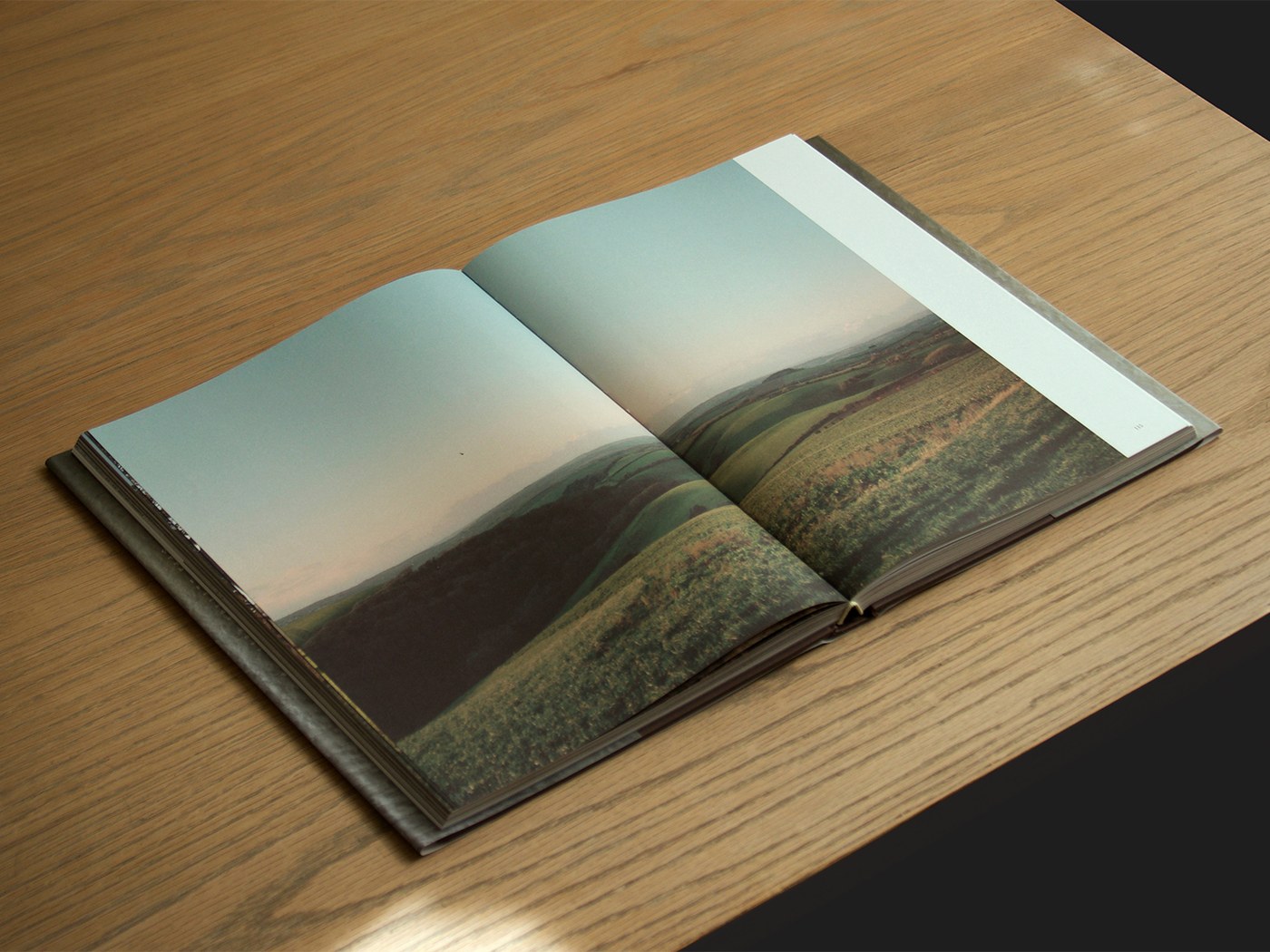

It took another year, then two, to find the right publisher. Once met, it was clear that Thames & Hudson was it. Patient editors and the trust of trusting directors allowed the book to take the time it needed to. I never thought I’d be allowed to fill a page with an abstract photo of light falling in the corner of a building or a landscape without buildings in an architectural book, but both are there. The book was allowed to breathe and have a beat.

Four quick chapter précis written in a hurry for a publisher’s deadline over a glass or two of wine became leitmotifs for the chapter essays I found it very hard to move beyond. I rear and re-read them for a week on the remote Greek Island of Patmos, failed to add a word and left only with the realisation that I needed to bin them and start anew. It was another two years before the actual essays were written.

Writing can be as slow as building.

The introduction Quietude I took with me for a Covid-era August with friends in Sicily whose villa would otherwise have been rented out all summer long. I thought it would be easy to whip my notes into shape. I was wrong, and an unrelaxed guest. Another year.

I (over)stayed at a friend’s house in Umbria the next August to write the chapter essays. Each morning I went for a walk and spoke them to the hills. Just as I was feeling I couldn’t (out)stay my stay any longer, the essays came together. They were written together and interweave, became a quartet. On the last day I was finally ready to let Scott, an art history professor and PhD supervisor, read them. He came through from his study and said They are beautiful. And then pointed out that I’d used the word perhaps six times in the first page.

The painful part of writing is having to go backwards to go forwards, to undo a knot and get it looser before it can be tightened up. The fear of losing what you had, the first thought. My two concerns were to make the words understandable to non-architects (architectural writing does not on the whole go in for understandability), and to hold to what I’d written in five, ten, twenty years, an impossible thing to know and to aim for, but once I’d had the thought I couldn’t lose it. The same holds for the book as a whole: I cared very much that it wouldn’t feel dated in two years’ time. I guess it’s the same as my buildings.

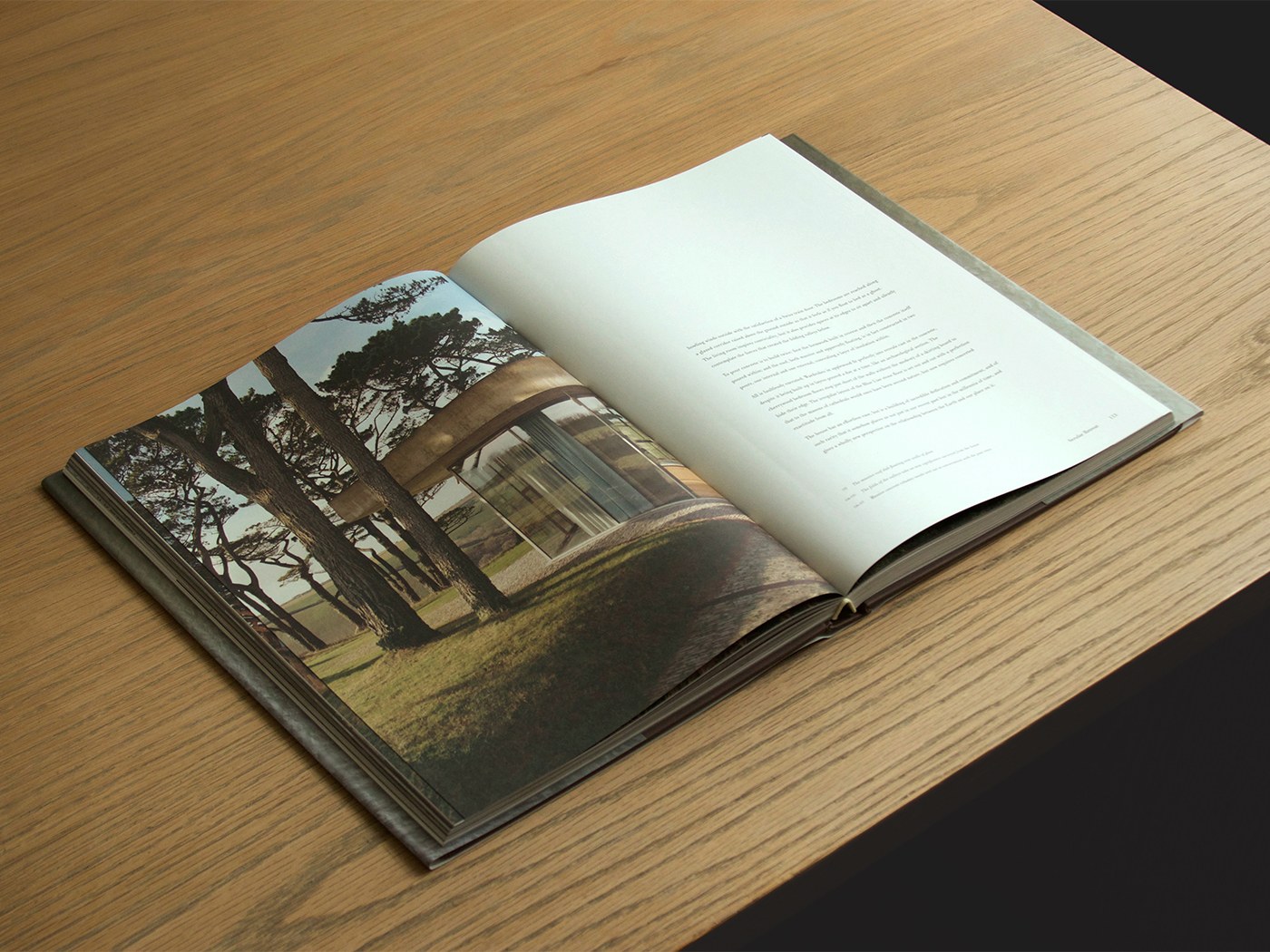

It was part of the conception that the photos would be taken for the book, that all the places would be presented thought a single eye. I also wanted it to be shot on film, for romantic notions mostly, but also for reasons to do with the analogue, and the camera lens working like the human eye. The photography took three years.

Harry Crowder, the photographer, had been sent my way by a friend. First he shot my flat. Then a client’s. His eye is freer than mine, and his photos seem to capture the experience of being in the spaces. They have soul. Once he’d agreed to take the book on, we discovered film was in short supply and he bought the world’s supply, and a fridge to house it in (like wine, film keeps better chilled).

Our trips punctuated real life for a few years, their timing dictated initially by seasons, and then the vicissitudes of Covid-19. Owners gave generous permissions, and for every shoot the sun shone on the day, even when it had been forecast not to. There came magical moments: to be alone in a Palladio villa under its six metre ceilings; to have Kettle’s Yard with just a curator to check that we hadn’t stolen any pebbles (unconscionable of course); to watch the same dawn sun that Barbara Hepworth watched rising over the far bay of St Ives and falling on and the sculptures in her garden; to have the magic of Lunuganga to ourselves (the story of that trip was written up for the FT).

For my own projects there was the delight in going back years after completion to shoot them again, to see them afresh, inhabited and populated, and the realisation that their owners, our clients, make them better. A wonderful and humbling lesson to learn.

Shooting, Harry goes into a sort of trance, seeing through his lens as an eye. I learnt that I didn’t have much to add and to let him be. There was always one shot from a shoot that when the first scans came in and were looked over in the office got a gasp.

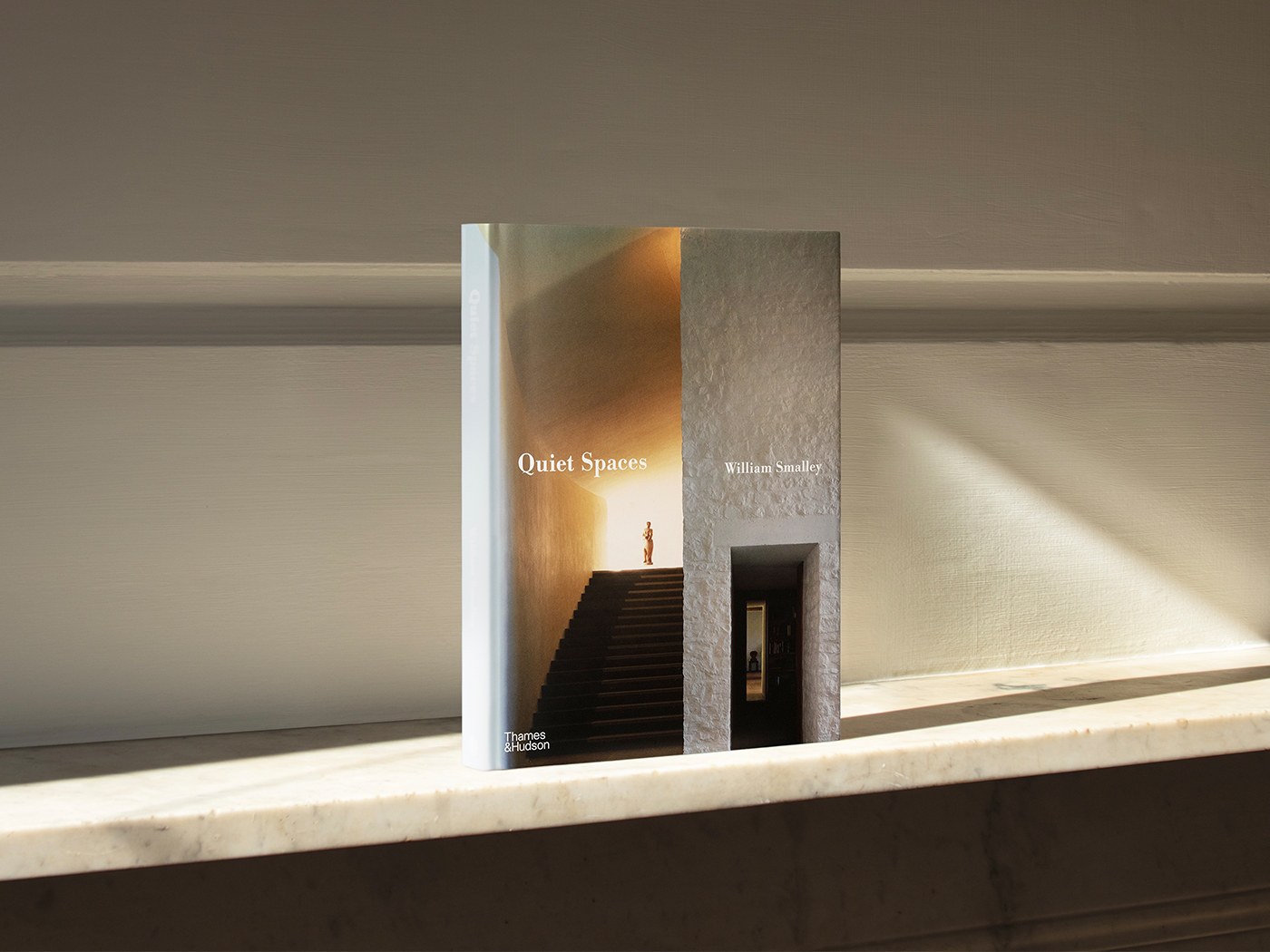

It was important to me that the book had a title that captured a mood, and was not just my name It changed along the journey; Quiet Spaces came after pinning the first shoots on the wall, and seeing in them a shared quietude that held them together.

The layout was made in dialogue between Luke Fenech, the book’s designer, and me, with incredible patience on Luke‘s part. I messed with his head early on by saying we should just put the text where it looked right on the page, and then set up an overarching grid from that. He wanted to start from the grid, which having been through the whole design process I now understand. But then, when he came to lay a regular grid over the randomly placed text, it aligned more or less to the millimetre. Unlikely pages took huge time to set out, hours spent late into the night, like the words of the text a mess until they coalesced. I have a new understanding and respect for the art of typography. I care and yet struggle to come to decisions. The worst type of client.

I spent a contented New Year pinning the pages up on the wall into an order. And then it was handed in, and I thought I was done, that the rest would be sorted with me now an onlooker. It turns out that is not how a book is made. Like a building, a book is made of thousands of tiny decisions, of any one of which threatens the peace of the perfect whole you are assembling. The cover is approved by committee. It took six months and a firm deadline to agree: a crop of an Hélène Binet image that in the end was perfect I think. Light comes out, and you feel you can put your hand into the space.

When there was enough of a book together to give an idea of it, I sent what there was to acclaimed potter and writer and friend Edmund de Waal to ask if he would write the foreword. It was reading his words that made the book real to me. When they came through, I realised I’d forgotten in my excitement that they would overshadow mine in their elegance and clarity. He writes of sensing a “feeling for the kindness of materials”.

Seeing the first proof copy of the book I thought would be emotional, but in truth I felt only numb. In fact, right until it was published it felt like a very extravagant and self-indulgent private passion project. Which it is partly, and would be, except that four thousand copies have been sent from the printers in China, books I will not meet, for readers I will not know, to be given to others hoping they will enjoy what I’ve written and collated.

It is both odd and not seeing everything laid out in the book, in bookshops. It feels inevitable and unknown. It was an instinctive process. I think it has made me want to be, prepared to be, bolder, truer. I enjoyed the act of deciding, as I do in my day job. Simple, true simplicity. Solid walls, and high ceilings were a recurrent theme, and have informed projects at home in London, and as far away as New Zealand. There is surprise at what I took with me: the air in Palladio, the birds at Lunuganga. There was delight in revisiting places, remembering, recording. But also what I didn’t take. Not perfection, no swankiness.

What does the book say? It is not a manifesto. It tries to describe, and not deny, something complex. It has preferences but it does not prescribe. Looking at it now with some distance, Quiet Spaces is a search for quietude, a record of not being able to relax until visual calm has been found, or, in our projects, achieved. The act of recording is an active one, as much a part of the studio as building. The book is a record of how I see.

—

My New Year’s resolution (or plan; I tend to go in for plans) this year was to start the next one. Something smaller, just words. Just words…

Chapter books:

Space from The Poetics of Space by French philosopher Gaston Bachelard, 1958;

Silence from A Time to Keep Silence by travel writer Patrick Leigh Fermor, 1953;

Shadows from In Praise of Shadows by Japanese writer Jun’ichiro Tanizaki, 1933; and

Life from A Way of Life by the creator of Kettle’s Yard, Jim Ede, 1984.