ix 25

The Chapel

In fact a gallery-studio for artist Marianna Kennedy at the rear of her listed 1727 house in London’s Spitalfields, it became fondly known as The Chapel during an earlier design iteration; the design moved on but the name stuck.

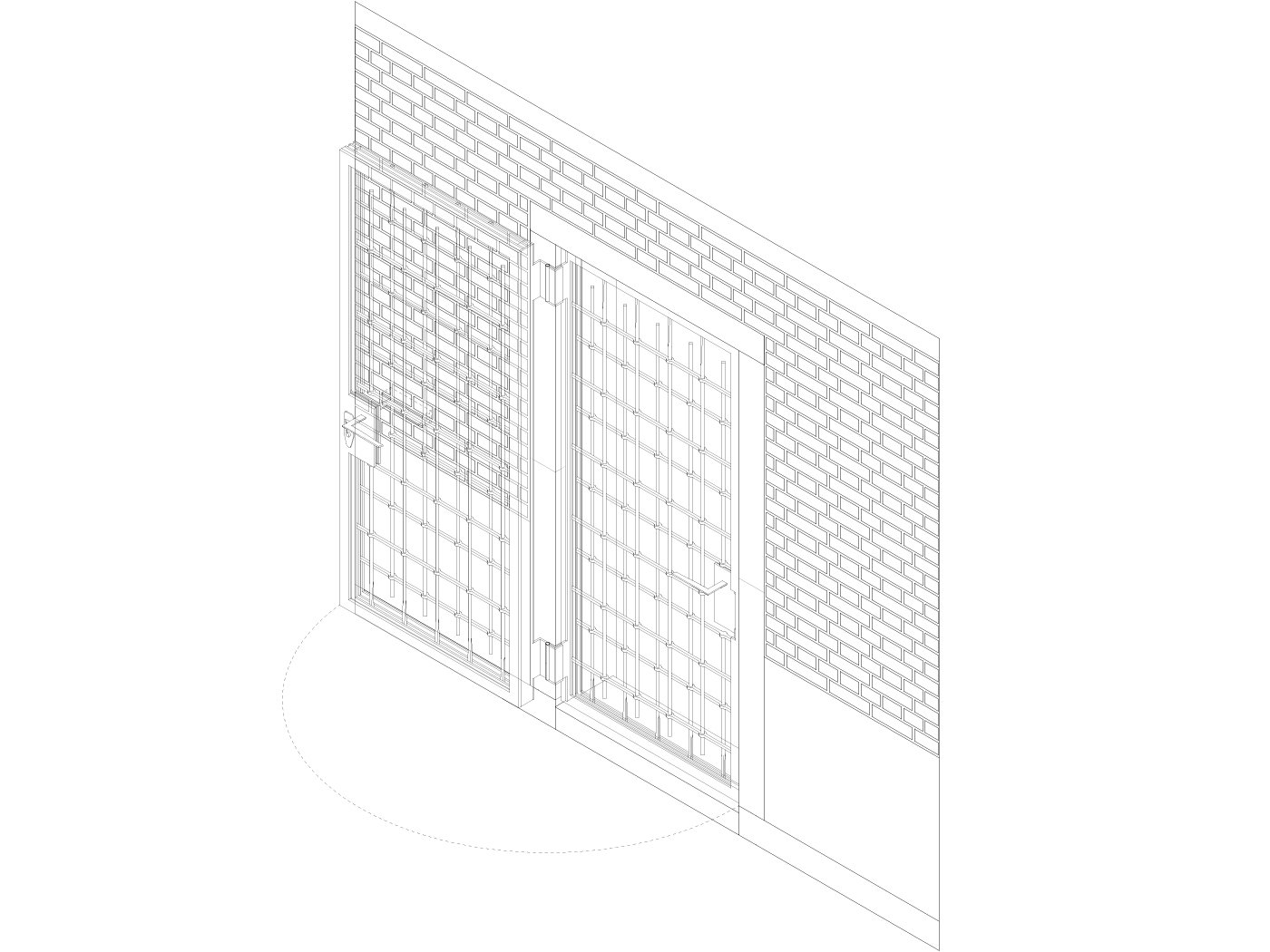

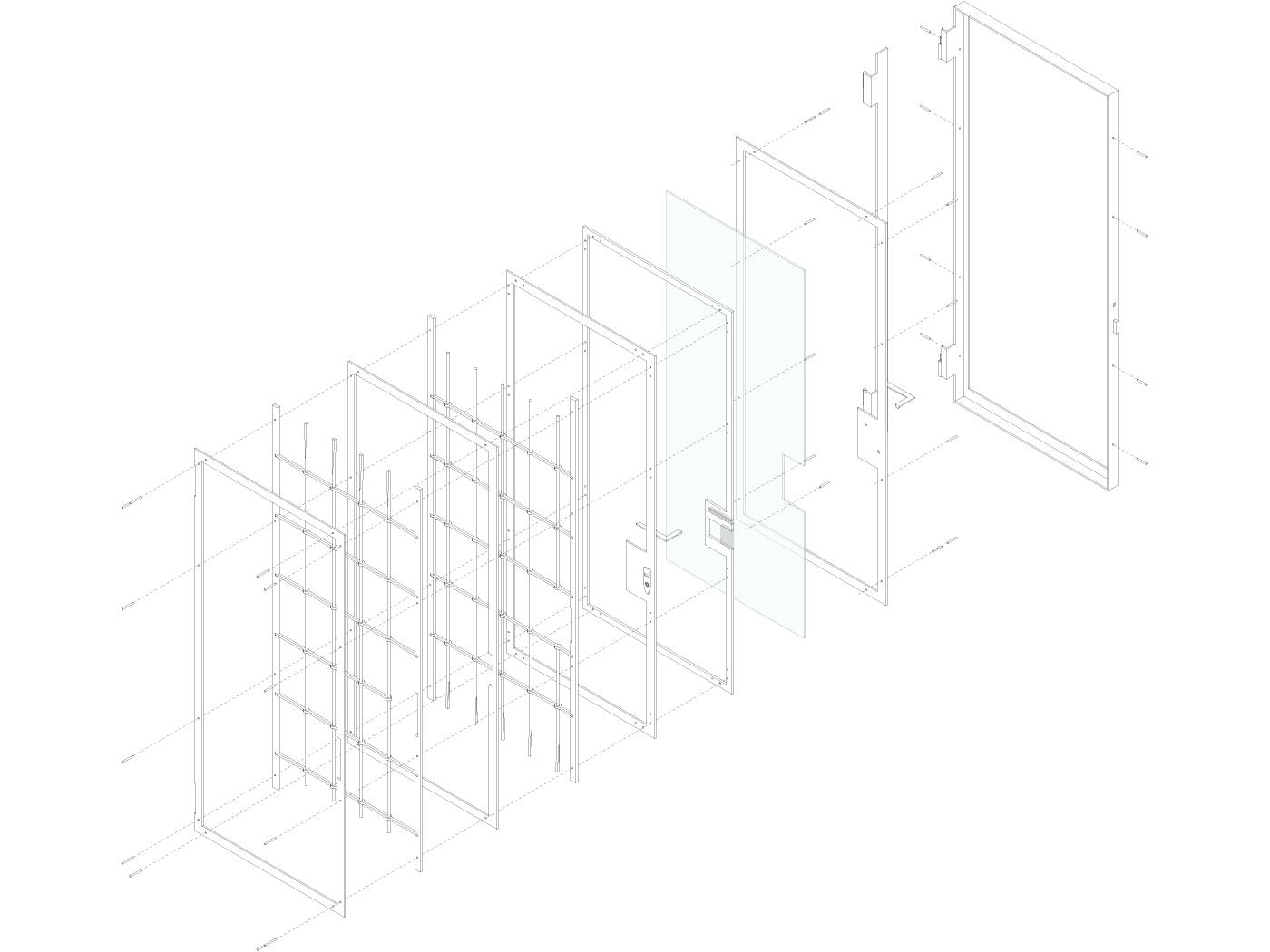

The house it sits behind is interesting for London in being four windows wide but only one room deep, with a door at each end of the street front, one into the house and the other now again leading into an open vaulted passageway to an outer courtyard, newly-formed with a wall of locally-reclaimed mediaeval bricks and dressed Portland stone. These frame a central glazed metal gate, designed in offset layers to be seen askance on approach.

The gate, as the other metalwork of the project, was fabricated by the Zanon brothers Paolo and Francesco in their workshop in Venice. Now in their 80s, they produced much of the finely wrought metalwork of celebrated Venetian architect Carlo Scarpa’s oeuvre in the latter 20th century – and are now repairing their earlier work.

The gate leads straight into the gallery, a perfect three-metre cube, three of its walls in soft, almost immaterial, limewashed render, and with a poured lime floor.

Now, in retrospect, the space speaks to me of Filippo Brunelleschi‘s early Renaissance Old Sacristy (1421-40), and Pazzi chapels (1443-78) in Florence, their mathematically pure white space defined with thin, almost drawn, lines of stone; here by the metal elements: skirting and the inverted shadows within the structural roof steels, supporting the roof of two sheets of glass, etched to shield close neighbours, the milkiness making the ceiling plane float beyond touch above, like Brunelleschi’s domes. The fourth side has asymmetric glazed metal doors that extend the space into a second, cobbled and ivy-walled, courtyard. A flush jib door connects to the back of the house.

In some ways a standard London house, its street façade has a grandeur and architectural ambition that belie its compact dimensions behind. The Chapel manages, similarly, to feel inevitable and unexpected, at once a small space and a grandly generous one. It is an excellent space for martinis.

Its precision stands in contrast perhaps to the flimsy, and after 300 years now crooked original house (there is the feeling that the Huguenots who built it would be surprised to find it still standing, and even venerated). The extension was commissioned to be of equal quality and care to the original house, without aping it. Instead, old and new share more abstract qualities, of intent, a shared purity and pared materiality, themes shared with Marianna’s work, and also too of her husband Charles Gledhill’s, a binder of rare books from his workshop in the house’s attic.

The past is alive here. The old is stitched, patched, replaced and improved, and the new the same.

Photography Ollie Bingham & Enrico Fiorese